4.4 Inflation and Interest Rates

As we first discussed in Chapter 3, interest rates are among the most important macroeconomic variables. In essence, they are the prices that link the present and the future. Here we discuss the relationship between inflation and interest rates.

Two Interest Rates: Real and Nominal

Suppose you deposit your savings in a bank account that pays 8 percent interest annually. Next year, you withdraw your savings and the accumulated interest. Are you 8 percent richer than you were when you made the deposit a year earlier?

The answer depends on what “richer” means. Certainly, you have 8 percent more dollars than you had before. But if prices have risen, so that each dollar buys less, then your purchasing power has not risen by 8 percent. If the inflation rate was 5 percent, then the amount of goods you can buy has increased by only 3 percent. And if the inflation rate was 10 percent, then your purchasing power actually fell by 2 percent.

The interest rate that the bank pays is called the nominal interest rate and the increase in your purchasing power is called the real interest rate. If i denotes the nominal interest rate, r the real interest rate, and π the rate of inflation, then the relationship among these three variables can be written as

r = i – π

The real interest rate is the difference between the nominal interest rate and the rate of inflation.5

The Fisher Effect

Rearranging terms in our equation for the real interest rate, we can show that the nominal interest rate is the sum of the real interest rate and the inflation rate:

i = r + π.

The equation written in this way is called the Fisher equation, after economist Irving Fisher (1867–1947). It shows that the nominal interest rate can change for two reasons: because the real interest rate changes or because the inflation rate changes.

Once we separate the nominal interest rate into these two parts, we can use this equation to develop a theory that explains the nominal interest rate. Chapter 3 showed that the real interest rate adjusts to equilibrate saving and investment. The quantity theory of money shows that the rate of money growth determines the rate of inflation. The Fisher equation then tells us to add the real interest rate and the inflation rate together to determine the nominal interest rate.

The quantity theory and the Fisher equation together tell us how money growth affects the nominal interest rate. According to the quantity theory, an increase in the rate of money growth of 1 percent causes a 1 percent increase in the rate of inflation. According to the Fisher equation, a 1 percent increase in the rate of inflation in turn causes a 1 percent increase in the nominal interest rate. The one-for-one relation between the inflation rate and the nominal interest rate is called the Fisher effect.

CASE STUDY

Inflation and Nominal Interest Rates

How useful is the Fisher effect in explaining interest rates? To answer this question we look at two types of data on inflation and nominal interest rates.

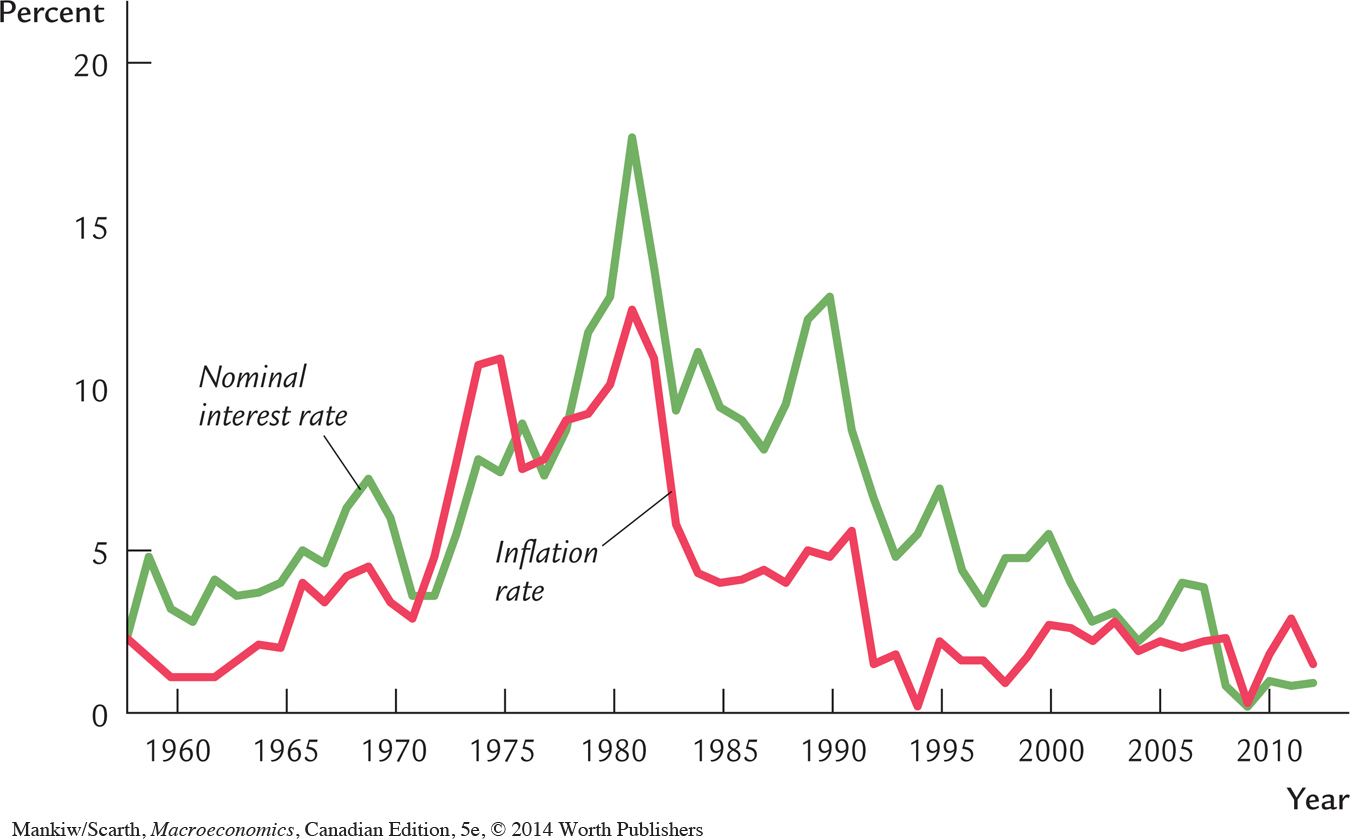

Figure 4-3 shows the variation over time in the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate in Canada. You can see that the Fisher effect has done a good job of explaining fluctuations in the nominal interest rate over the past fifty years. When inflation is high, nominal interest rates are typically high, and when inflation is low, nominal interest rates are typically low as well.

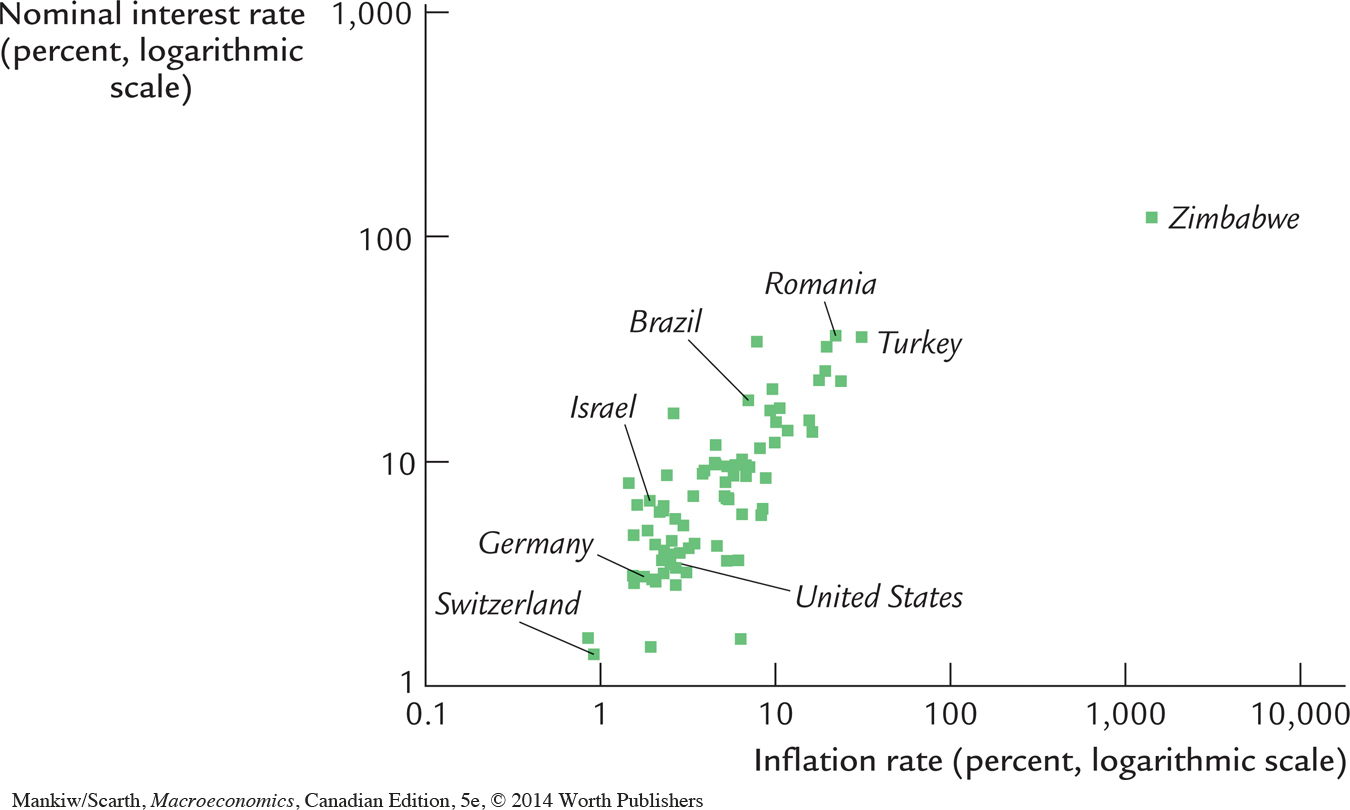

Similar support for the Fisher effect comes from examining the variation across countries at a single point in time. As Figure 4-4 shows, a nation’s inflation rate and its nominal interest rate are closely related. Countries with high inflation tend to have high nominal interest rates as well, and countries with low inflation tend to have low nominal interest rates.

The link between inflation and interest rates is well known to investment firms. Because bond prices move inversely with interest rates, one can get rich by predicting correctly the direction in which interest rates will move. Many investment firms hire central bank watchers to monitor monetary policy and news about inflation in order to anticipate changes in interest rates.

Two Real Interest Rates: Ex Ante and Ex Post

When a borrower and lender agree on a nominal interest rate, they do not know what the inflation rate over the term of the loan will be. Therefore, we must distinguish between two concepts of the real interest rate: the real interest rate that the borrower and lender expect when the loan is made, called the ex ante real interest rate, and the real interest rate that is actually realized, called the ex post real interest rate.

Although borrowers and lenders cannot predict future inflation with certainty, they do have some expectation about what the inflation rate will be. Let π denote actual future inflation and Eπ the expectation of future inflation. The ex ante real interest rate is i – Eπ, and the ex post real interest rate is i – π. The two real interest rates differ when actual inflation π differs from expected inflation Eπ.

How does this distinction between actual and expected inflation modify the Fisher effect? Clearly, the nominal interest rate cannot adjust to actual inflation, because actual inflation is not known when the nominal interest rate is set. The nominal interest rate can adjust only to expected inflation. The Fisher effect is more precisely written as

i = r + Eπ.

The ex ante real interest rate r is determined by equilibrium in the market for goods and services, as described by the model in Chapter 3. The nominal interest rate i moves one-for-one with changes in expected inflation Eπ.

CASE STUDY

Nominal Interest Rates in the Nineteenth Century

Although recent data show a positive relationship between nominal interest rates and inflation rates, this finding is not universal. In data from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, high nominal interest rates did not accompany high inflation. The apparent absence of any Fisher effect during this time puzzled Irving Fisher. He suggested that inflation “caught merchants napping.”

How should we interpret the absence of an apparent Fisher effect in nineteenth-century data? Does this period of history provide evidence against the adjustment of nominal interest rates to inflation? Recent research suggests that this period has little to tell us about the validity of the Fisher effect. The reason is that the Fisher effect relates the nominal interest rate to expected inflation and, according to this research, inflation at this time was largely unexpected.

Although expectations are not directly observable, we can draw inferences about them by examining the persistence of inflation. In recent experience, inflation has been highly persistent: when it is high one year, it tends to be high the next year as well. Therefore, when people have observed high inflation, it has been rational for them to expect high inflation in the future. By contrast, during the nineteenth century, when the gold standard was in effect, inflation had little persistence. High inflation in one year was just as likely to be followed the next year by low inflation as by high inflation. Therefore, high inflation did not imply high expected inflation and did not lead to high nominal interest rates. So, in a sense, Fisher was right to say that inflation “caught merchants napping.” 6