15.2 Should Policy Be Conducted by Rule or by Discretion?

A second topic of debate among economists is whether economic policy should be conducted by rule or by discretion. Policy is conducted by rule if policymakers announce in advance how policy will respond to various situations and commit themselves to following through on this announcement. Policy is conducted by discretion if policymakers are free to size up events as they occur and choose whatever policy they consider appropriate at the time.

The debate over rules versus discretion is distinct from the debate over passive versus active policy. Policy can be conducted by rule and yet be either passive or active. For example, a passive policy rule might specify steady growth in the money supply of 2 percent per year. An active policy rule might specify that

Money Growth = 2% + (Unemployment Rate – 7%).

Under this rule, the money supply grows at 2 percent if the unemployment rate is 7 percent, but for every percentage point by which the unemployment rate exceeds 7 percent, money growth increases by an extra percentage point. This rule tries to stabilize the economy by raising money growth when the economy is in a recession.

We begin this section by discussing why policy might be improved by a commitment to a policy rule. We then examine several possible policy rules.

Distrust of Policymakers and the Political Process

Some economists believe that economic policy is too important to be left to the discretion of policymakers. Although this view is more political than economic, evaluating it is central to how we judge the role of economic policy. If politicians are incompetent or opportunistic, then we may not want to give them the discretion to use the powerful tools of monetary and fiscal policy.

Incompetence in economic policy arises for several reasons. Some economists view the political process as erratic, perhaps because it reflects the shifting power of special interest groups. In addition, macroeconomics is complicated, and politicians often do not have sufficient knowledge of it to make informed judgments. This ignorance allows charlatans to propose incorrect but superficially appealing solutions to complex problems. The political process often cannot weed out the advice of charlatans from that of competent economists.

Opportunism in economic policy arises when the objectives of policymakers conflict with the well-being of the public. Some economists fear that politicians use macroeconomic policy to further their own electoral ends. If citizens vote on the basis of economic conditions prevailing at the time of the election, then politicians have an incentive to pursue policies that will make the economy look good during election years. A new government might cause a recession soon after coming into office to lower inflation and then stimulate the economy as the next election approaches to lower unemployment; this would ensure that both inflation and unemployment are low on election day. Manipulation of the economy for electoral gain, called the political business cycle, has been the subject of extensive research by economists and political scientists.5

Politicians have not fully abided by the principles set out in the 1945 White Paper on income and employment. We noted earlier that this statement of government intent involved the government’s increasing the national debt during recessions, by having spending exceed taxes when the economy might benefit from stimulation. Most politicians like this message—it excuses budget deficits. Indeed, it is based on the proposition that running a deficit is the responsible policy in some instances. But many politicians seem to have ignored a later section of the White Paper, in which it is clearly stated that “in periods of buoyant employment and income, budget plans will call for surpluses.” If this part of the White Paper’s advice had been heeded, then Canadians would have witnessed budget surpluses as often as budget deficits. The result would have been no long-run increase in the national debt, such as what we observed from the early 1970s until the mid-1990s.

Distrust of the political process leads some economists to advocate placing economic policy outside the realm of politics. Some have proposed constitutional amendments, such as a balanced-budget amendment, that would tie the hands of legislators and insulate the economy from both incompetence and opportunism.

The Time Inconsistency of Discretionary Policy

If we assume that we can trust our policymakers, discretion at first glance appears superior to a fixed policy rule. Discretionary policy is, by its nature, flexible. As long as policymakers are intelligent and benevolent, there might appear to be little reason to deny them flexibility in responding to changing conditions.

Yet a case for rules over discretion arises from the problem of time inconsistency of policy. In some situations policymakers may want to announce in advance the policy they will follow in order to influence the expectations of private decisionmakers. But later, after the private decisionmakers have acted on the basis of their expectations, these policymakers may be tempted to renege on their announcement. Understanding that policymakers may be inconsistent over time, private decisionmakers are led to distrust policy announcements. In this situation, to make their announcements credible, policymakers may want to make a commitment to a fixed policy rule.

Time inconsistency is illustrated most simply in a political rather than an economic example—specifically, public policy about negotiating with terrorists over the release of hostages. The announced policy of many nations is that they will not negotiate over hostages. Such an announcement is intended to deter terrorists: if there is nothing to be gained from kidnapping hostages, rational terrorists won’t kidnap any. In other words, the purpose of the announcement is to influence the expectations of terrorists and thereby their behaviour.

But, in fact, unless the policymakers are credibly committed to the policy, the announcement has little effect. Terrorists know that once hostages are taken, policymakers face an overwhelming temptation to make some concession to obtain the hostages’ release. The only way to deter rational terrorists is to take away the discretion of policymakers and commit them to a rule of never negotiating. If policymakers were truly unable to make concessions, the incentive for terrorists to take hostages would be largely eliminated.

The same problem arises less dramatically in the conduct of monetary policy. Consider the dilemma of a central bank that cares about both inflation and unemployment. According to the Phillips curve, the tradeoff between inflation and unemployment depends on expected inflation. The Bank of Canada would prefer everyone to expect low inflation so that it will face a favourable tradeoff. To reduce expected inflation, the Bank of Canada often announces that low inflation is the paramount goal of monetary policy.

But an announcement of a policy of low inflation is by itself not credible. Once households and firms have formed their expectations of inflation and set wages and prices accordingly, the Bank of Canada has an incentive to renege on its announcement and implement expansionary monetary policy to reduce unemployment. People understand the Bank’s incentive to renege and therefore do not believe the announcement in the first place. Just as a government leader facing a hostage crisis is sorely tempted to negotiate their release, a central bank with discretion is sorely tempted to inflate in order to reduce unemployment. And just as terrorists discount announced policies of never negotiating, households and firms discount announced policies of low inflation.

The surprising outcome of this analysis is that policymakers can sometimes better achieve their goals by having their discretion taken away from them. In the case of rational terrorists, fewer hostages will be taken and killed if policymakers are committed to following the seemingly harsh rule of refusing to negotiate for hostages’ freedom. In the case of monetary policy, there will be lower inflation without higher unemployment if the Bank of Canada is committed to a policy of zero inflation. (This conclusion about monetary policy is modelled more explicitly in the appendix to this chapter.)

The time inconsistency of policy arises in many other contexts. Here are some examples:

To encourage investment, the government announces that it will not tax income from capital. But after factories have been built, the government is tempted to renege on its promise because the taxation of existing capital does not distort economic incentives. (Individuals will not destroy existing capital just to avoid taxes.)

To encourage research, the government announces that it will give a temporary monopoly to companies that discover new drugs. But after a drug has been discovered, the government is tempted to revoke the patent or to regulate the price to make the drug more affordable.

To encourage good behaviour, a parent announces that he or she will punish a child whenever the child breaks a rule. But after the child has misbehaved, the parent is tempted to forgive this transgression, because punishment is unpleasant for the parent as well as for the child.

To encourage you to work hard, your professor announces that this course will end with an exam. But after you have studied and learned all the material, the professor is tempted to cancel the exam so that he or she won’t have to grade it.

In each case, rational agents understand the incentive for the policymaker to renege, and this expectation affects their behaviour. And in each case, the solution is to take away the policymaker’s discretion with a credible commitment to a fixed policy rule.

CASE STUDY

Alexander Hamilton Versus Time Inconsistency

Time inconsistency has long been a problem associated with discretionary policy. In fact, it was one of the first problems that confronted Alexander Hamilton when President George Washington appointed him the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury in 1789.

Hamilton faced the question of how to deal with the debts that the new nation had accumulated as it fought for its independence from Britain. When the revolutionary government incurred the debts, it promised to honour them when the war was over. But after the war, many Americans advocated defaulting on the debt because repaying the creditors would require taxation, which is always costly and unpopular.

Hamilton opposed the time-inconsistent policy of repudiating the debt. He knew that the nation would likely need to borrow again sometime in the future. In his First Report on the Public Credit, which he presented to Congress in 1790, he wrote

If the maintenance of public credit, then, be truly so important, the next inquiry which suggests itself is: By what means is it to be effected? The ready answer to which question is, by good faith; by a punctual performance of contracts. States, like individuals, who observe their engagements are respected and trusted, while the reverse is the fate of those who pursue an opposite conduct.

Thus, Hamilton proposed that the nation make a commitment to the policy rule of honouring its debts.

The policy rule that Hamilton originally proposed has continued for over two centuries. Today, unlike in Hamilton’s time, when most governments debate spending priorities, people do not propose defaulting on the public debt. However, there have been exceptions. For example, the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan defaulted on their debts in the 1930s, several developing countries were forgiven part of their international debts in the 1980s, and (as we discuss in Chapter 20) some European countries are not fully covering their debts as this book goes to press. Nevertheless, these exceptions represent extreme situations in which alternative actions were extraordinarily difficult. In the case of public debt, almost everyone now agrees that the government should be committed to a fixed policy rule.

Rules for Monetary Policy

Even if we are convinced that policy rules are superior to discretion, the debate over macroeconomic policy is not over. If the Bank of Canada were to commit to a rule for monetary policy, what rule should it choose? Let’s discuss briefly three policy rules that various economists advocate.

Some economists, called monetarists, advocate that the Bank of Canada keep the money supply growing at a steady rate. The quotation at the beginning of this chapter from Milton Friedman—the most famous monetarist—exemplifies this view of monetary policy. Monetarists believe that fluctuations in the money supply are responsible for most large fluctuations in the economy. They argue that slow and steady growth in the money supply would yield stable output, employment, and prices.

Although a monetarist policy rule might have prevented many of the economic fluctuations we have experienced historically, most economists believe that it is not the best possible policy rule. Steady growth in the money supply stabilizes aggregate demand only if the velocity of money is stable. But the variations in velocity in the 1980s, which we discussed in Chapter 9, show that velocity is sometimes unpredictable. Most economists believe that a policy rule needs to allow the money supply to adjust to various shocks to the economy.

A second policy rule that economists widely advocate is nominal GDP targeting. Under this rule, the Bank of Canada announces a planned path for nominal GDP. If nominal GDP rises above the target, the Bank of Canada reduces money growth to dampen aggregate demand. If it falls below the target, the Bank of Canada raises money growth to stimulate aggregate demand. Since a nominal GDP target allows monetary policy to adjust to changes in the velocity of money, most economists believe it would lead to greater stability in output and prices than a monetarist policy rule.

A third policy rule that is often advocated is inflation targeting. Under this rule, the Bank of Canada announces a target for the inflation rate (usually a low one) and then adjusts the interest rate (and ultimately the money supply) when the actual inflation deviates from the target. Like nominal GDP targeting, inflation targeting insulates the economy from changes in the velocity of money. In addition, an inflation target has the political advantage that it is easy to explain to the public.

Notice that all these rules are expressed in terms of some nominal variable—the money supply, nominal GDP, or the price level. One can also imagine policy rules expressed in terms of real variables. For example, the Bank of Canada might try to target the unemployment rate at 5 percent. The problem with such a rule is that no one knows exactly what the natural rate of unemployment is. If the Bank of Canada chose a target for the unemployment rate below the natural rate, the result would be accelerating inflation. Conversely, if the Bank of Canada chose a target for the unemployment rate above the natural rate, the result would be accelerating deflation. For this reason, economists rarely advocate rules for monetary policy expressed solely in terms of real variables, even though real variables such as unemployment and real GDP are the best measures of economic performance.

CASE STUDY

Inflation Targeting: Rule or Constrained Discretion?

Since the late 1980s, many of the world’s central banks—including those of Australia, Canada, Finland, Israel, New Zealand, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom—adopted some form of inflation targeting. Sometimes inflation targeting takes the form of a central bank announcing its policy intentions. In Canada’s case, the federal Minister of Finance and the governor of the Bank of Canada set a target band of 1–3 percent for the inflation rate since 1996. Initially, the target was for what was referred to as core inflation, which excludes the eight most volatile components of the CPI, as well as the effect of indirect taxes on the remaining components.

Other times the inflation target takes the form of a national law that spells out the goals of monetary policy. For example, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act of 1989 told the central bank “to formulate and implement monetary policy directed to the economic objective of achieving and maintaining stability in the general level of prices.” The act conspicuously omitted any mention of any other competing objective, such as stability in output, employment, interest rates, or exchange rates.

Should we interpret inflation targeting as a type of precommitment to a policy rule? Not completely. In all the countries that have adopted inflation targeting, central banks are left with a fair amount of discretion. Inflation targets are usually set as a range—for example, an inflation rate of 1 to 3 percent in Canada’s case—rather than a particular number. Thus, the central bank can choose where in the range it wants to be: it can stimulate the economy and be near the top of the range, or dampen the economy and be near the bottom. In addition, the central banks are sometimes allowed to adjust their targets for inflation, at least temporarily, if some exogenous event (such as an easily identified supply shock such as the introduction of the GST or its reduction by two percentage points in recent years) pushes inflation outside of the range that was previously announced.

In light of this flexibility, what is the purpose of inflation targeting? Although inflation targeting does leave the central bank with some discretion, the policy does constrain how this discretion is used. When a central bank is told simply to “do the right thing,” it is hard to hold the central bank accountable, for people can argue forever about what the right thing is in any specific circumstance. By contrast, when a central bank has announced an inflation target, the public can more easily judge whether the central bank is meeting that target. Thus, although inflation targeting does not tie the hands of the central bank, it does increase the transparency of monetary policy and, by doing so, makes central bankers more accountable for their actions.6

CASE STUDY

Central Bank Independence

Suppose you were put in charge of writing the constitution and laws for a country. Would you give the political leader of the country authority over the policies of the central bank? Or would you allow the central bank to make decisions free from such political influence? In other words, assuming that monetary policy is made by discretion rather than by rule, who should exercise that discretion?

Countries vary greatly in how they choose to answer this question. In some countries, the central bank is a branch of the government; in others, the central bank is largely independent. In Canada, the Governor of the Bank of Canada is appointed for a 7-year term. The Governor must resign if he or she does not wish to implement the monetary policy of the government. But the government must put its detailed instructions in writing and on public record, so the Governor has significant power if there is a disagreement. In the United States, Fed governors are appointed by the president for 14-year terms, and they cannot be recalled if the president is unhappy with their decisions. This institutional structure gives the Fed a degree of independence similar to that of the Supreme Court.

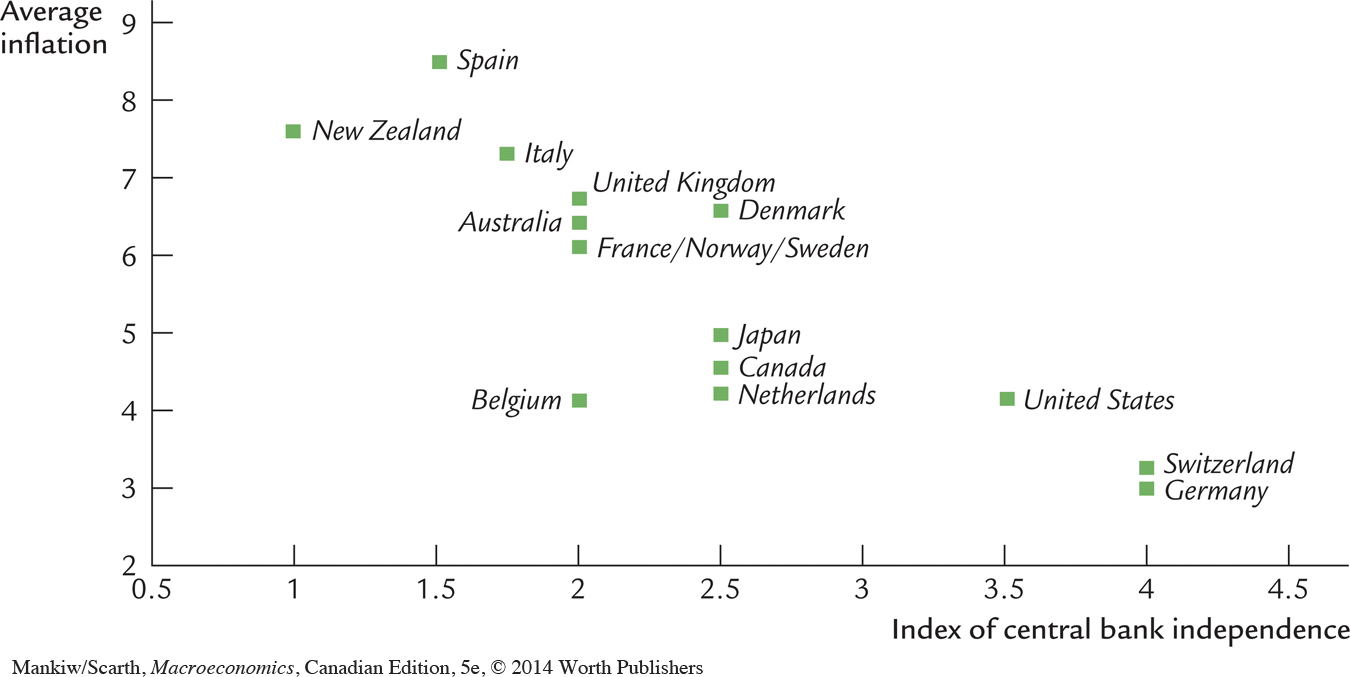

Many researchers have investigated the effects of constitutional design on monetary policy. They have examined the laws of different countries to construct an index of central bank independence. This index is based on various characteristics, such as the length of bankers’ terms, the role of government officials on the bank board, and the frequency of contact between the government and the central bank. The researchers have then examined the correlation between central bank independence and macroeconomic performance.

The results of these studies are striking: more independent central banks are strongly associated with lower and more stable inflation. Figure 15-2 shows a scatterplot of central bank independence and average inflation for the period 1955 to 1988. Countries that had an independent central bank, such as Germany, Switzerland, and the United States, tended to have low average inflation. Countries that had central banks with less independence, such as New Zealand and Spain, tended to have higher average inflation.

Researchers have also found there is no relationship between central bank independence and real economic activity. In particular, central bank independence is not correlated with average unemployment, the volatility of unemployment, the average growth of real GDP, or the volatility of real GDP. Central bank independence appears to offer countries a free lunch: it has the benefit of lower inflation without any apparent cost. This finding has led some countries, such as New Zealand, to rewrite their laws to give their central banks greater independence.7

CASE STUDY

The Bank of Canada’s Low-Inflation Target: Implications for Fiscal Policy

In an effort to acquire credibility as an inflation-fighter, the Bank of Canada has repeatedly emphasized since 1987 that its sole target is price stability. In 1996, in an attempt to show its support for a slightly more flexible form of this commitment, the federal government published its (and the Bank’s) inflation target for the next 5 years—that the annual rise in the CPI stay within the 1–3 percent range. The commitment to this target range has been extended since, and it still applies today.

The Bank of Canada continues to argue that reducing unemployment is not part of what it sees as its mandate. Many Canadians are critical of the Bank’s taking this narrow view; they want the Bank of Canada to care about unemployment, too. Some of those criticizing the Bank of Canada ignore the fact that the Bank officials are not strict monetarists, and that, by pursuing an inflation rate close to zero, the Bank of Canada will automatically help to stabilize employment. We are now in a position to appreciate this important implication of the Bank of Canada’s monetary rule.

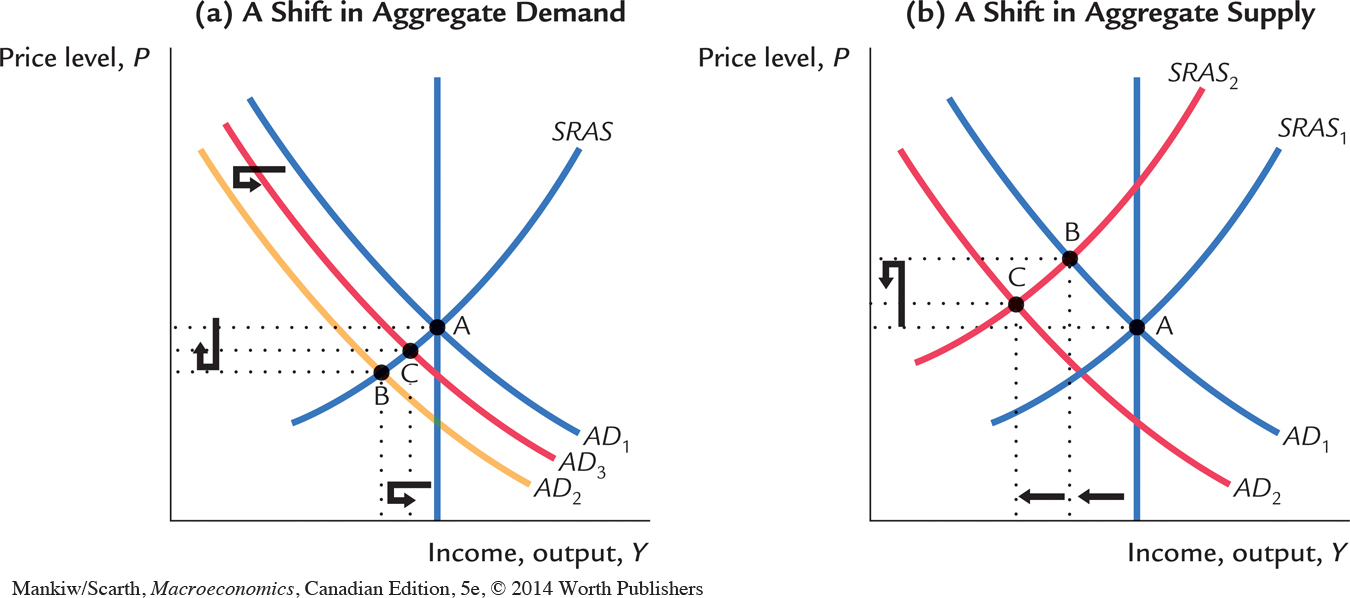

Consider a decrease in aggregate demand, as shown in panel (a) of Figure 15-3. If the Bank of Canada holds the money supply constant, the economy moves from point A to point B in the short run, and a recession occurs. But some deflation in prices occurs as well, and this evokes an automatic reaction from the Bank of Canada if it has adopted a zero-inflation target instead of a constant money supply rule. To implement a zero-inflation target, the Bank of Canada must increase the money supply whenever there is a downward pressure on the price level (as shown in panel (a) of Figure 15-3). Even if the Bank does not fully accomplish its goal, the result is that the aggregate demand curve shifts somewhat back to the right. The economy ends up at point C, and the magnitude of the recession is reduced. Thus, as far as aggregate demand disturbances are concerned, inflation targeting involves the very built-in stabilization feature that many Bank of Canada critics want the economy to have. So the Bank of Canada does care about unemployment, even if indirectly.

One way of interpreting this analysis is to say that inflation targeting makes fiscal-policy multipliers smaller than they would otherwise be. Inflation targeting reduces the importance of both the undesired shifts in the aggregate demand curve and the shifts that are deliberately planned by fiscal policy. So a high degree of built-in stability involves good news and bad. The good news is that unforeseen events have a limited effect on unemployment; the bad news is that demand policies that are intended to lower unemployment by shifting aggregate demand to the right have limited effects as well.

In Chapter 11, we noted that the numerical estimates of fiscal-policy multipliers from macroeconometric models have been falling in recent years. We can now appreciate another reason why this trend in estimated multiplier values is not something we should find surprising. The Bank of Canada has switched from money-growth targeting to inflation targeting.

What about aggregate supply shocks? The effects of a leftward shift in the aggregate supply curve are shown in panel (b) of Figure 15-3. If the Bank of Canada holds the money supply constant in the face of this event, the economy moves from point A to point B. Again, a recession occurs, but in this case, it is accompanied by inflation, not deflation. If the Bank of Canada adopts a zero-inflation target, it must decrease the money supply in an attempt to reduce the upward pressure on prices. With this response accounted for, the economy moves to point C instead of point B, and the magnitude of the recession is made larger by monetary policy. Thus, inflation targeting is destabilizing in the face of supply-side shocks.

The Bank of Canada’s critics are concerned about limiting the losses in Canadian output and employment. But since this analysis shows that inflation targeting is stabilizing for demand shocks but destabilizing for supply shocks, it offers no clear verdict concerning the Bank of Canada and its critics. Because of this ambiguity, it is important to remember what was explained in the appendix to Chapter 12. The extended Mundell–Fleming analysis in that appendix indicates that a contractionary fiscal policy is like adverse supply shock since it generates lower output and pressure for higher prices. If the major shocks to hit our economy are spending cuts (as was the case throughout the 1990s), our analysis suggests that the critics of the Bank were correct at that time to be concerned about the employment implications of Canada’s monetary and fiscal policy mix. But when fiscal policy is expansionary, as it was in the recession of 2008–2009, these same critics should applaud the Bank of Canada’s commitment to price stability, since it leads the Bank to support Finance Canada’s initiative.