20.2 Financial Crises

So far in this chapter we have discussed how the financial system works. We now discuss why the financial system might stop working and the broad macroeconomic ramifications of such a disruption.

When we discussed the theory of the business cycle in Chapters 9 to 14, we saw that many kinds of shocks can lead to short-run fluctuations. A shift in consumer or business confidence, a rise or fall in world oil prices, or a sudden change in monetary or fiscal policy can alter aggregate demand or aggregate supply (or both). When this occurs, output and employment are pushed away from their natural levels, and inflation rises or falls as well.

Here we focus on one particular kind of shock. A financial crisis is a major disruption in the financial system that impedes the economy’s ability to intermediate between those who want to save and those who want to borrow and invest. Not surprisingly, given the financial system’s central role, financial crises have a broad macroeconomic impact. Throughout history, many of the deepest recessions have followed problems in the financial system. These downturns include the Great Depression of the 1930s and the recession of 2008–2009.

The Anatomy of a Crisis

Financial crises are not all alike, but they share some common features. In a nutshell, here are the six elements that are at the centre of most financial crises. The financial crisis of 2008–2009 provides a good example of each element.

1. Asset-Price Booms and Busts Often, a period of optimism, leading to a large increase in asset prices, precedes a financial crisis. Sometimes people bid up the price of an asset above its fundamental value (that is, the true value based on an objective analysis of the cash flows the asset will generate). In this case, the market for that asset is said to be in the grip of a speculative bubble. Later, when sentiment shifts and optimism turns to pessimism, the bubble bursts and prices begin to fall. The decline in asset prices is the catalyst for the financial crisis.

In 2008 and 2009, the crucial asset was residential real estate. The average price of housing in the United States had experienced a boom earlier in the decade. This boom was driven in part by lax lending standards; many subprime borrowers—those with particularly risky credit profiles—were lent money to buy a house while offering only a very small down payment. In essence, the financial system failed to do its job of dealing with asymmetric information by making loans to many borrowers who, it turned out, would later have trouble making their mortgage payments. The housing boom was also encouraged by government policies that promoted homeownership and was fed by excessive optimism on the part of home-buyers, who thought prices would rise forever. The housing boom, however, proved unsustainable. Over time, the number of homeowners falling behind on their mortgage payments rose, and sentiment among home-buyers shifted. Housing prices fell by about 30 percent from 2006 to 2009. The nation had not experienced such a large decline in housing prices since the 1930s.

2. Insolvencies at Financial Institutions A large decline in asset prices may cause problems at banks and other financial institutions. To ensure that borrowers repay their loans, banks often require them to post collateral. That is, a borrower has to pledge assets that the bank can seize if the borrower defaults. Yet when assets decline in price, the collateral falls in value, perhaps below the amount of the loan. In this case, if the borrower defaults on the loan, the bank may be unable to recover its money.

As we discussed in Chapter 19, banks rely heavily on leverage, the use of borrowed funds for the purposes of investment. Leverage amplifies the positive and negative effect of asset returns on a bank’s financial position. A key number is the leverage ratio: the ratio of bank assets to bank capital. A leverage ratio of 20, for example, means that for every $1 in capital put into the bank by its owners, the bank has borrowed (via deposits and other loans) $19, which then allows the bank to hold $20 in assets. In this case, if defaults cause the value of the bank’s assets to fall by 2 percent, then the bank’s capital will fall by 40 percent. If the value of bank assets falls by more than 5 percent, then its assets will fall below its liabilities, and the bank will be insolvent. In this case, the bank will not have the resources to pay off all its depositors and other creditors. Widespread insolvency within the financial system is the second element of a financial crisis.

In 2008 and 2009, many banks and other financial firms had in effect placed bets on real estate prices by holding mortgages backed by that real estate. They assumed that housing prices would keep rising or at least hold steady, so the collateral backing these loans would ensure their repayment. When housing prices fell, however, large numbers of homeowners found themselves underwater: the value of their homes was less than the amount they owed on their mortgages. When many homeowners stopped paying their mortgages, the banks could foreclose on the houses, but they could recover only a fraction of what they were owed. These defaults pushed several financial institutions toward bankruptcy. These institutions included major investment banks (Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers), government-sponsored enterprises involved in the mortgage market (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac), and a large insurance company (AIG).

3. Falling Confidence The third element of a financial crisis is a decline in confidence in financial institutions. While some deposits in banks are insured by government policies, not all are. As insolvencies mount, every financial institution becomes a possible candidate for the next bankruptcy. Individuals with uninsured deposits in those institutions pull out their money. Facing a rash of withdrawals, banks cut back on new lending and start selling off assets to increase their cash reserves.

As banks sell off some of their assets, they depress the market prices of these assets. Because buyers of risky assets are hard to find in the midst of a crisis, the assets’ prices can sometimes fall precipitously. Such a phenomenon is called a fire sale, similar to the reduced prices that a store might charge to get rid of merchandise quickly after a fire. These fire-sale prices, however, cause problems at other banks. Accountants and regulators may require these banks to revise their balance sheets and reduce the reported value of their own holdings of these assets. In this way, problems in one bank can spread to others.

In 2008 and 2009, the financial system was seized by great uncertainty about where the insolvencies would stop. The collapse of the giants Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers made people wonder whether other large financial firms, such as Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, and Citigroup, would meet a similar fate. The problem was exacerbated by the firms’ interdependence. Because they had many contracts with one another, the demise of any one of these institutions would undermine all the others. Moreover, because of the complexity of the arrangements, depositors could not be sure how vulnerable these firms were. The lack of transparency fed the crisis of confidence.

FYI

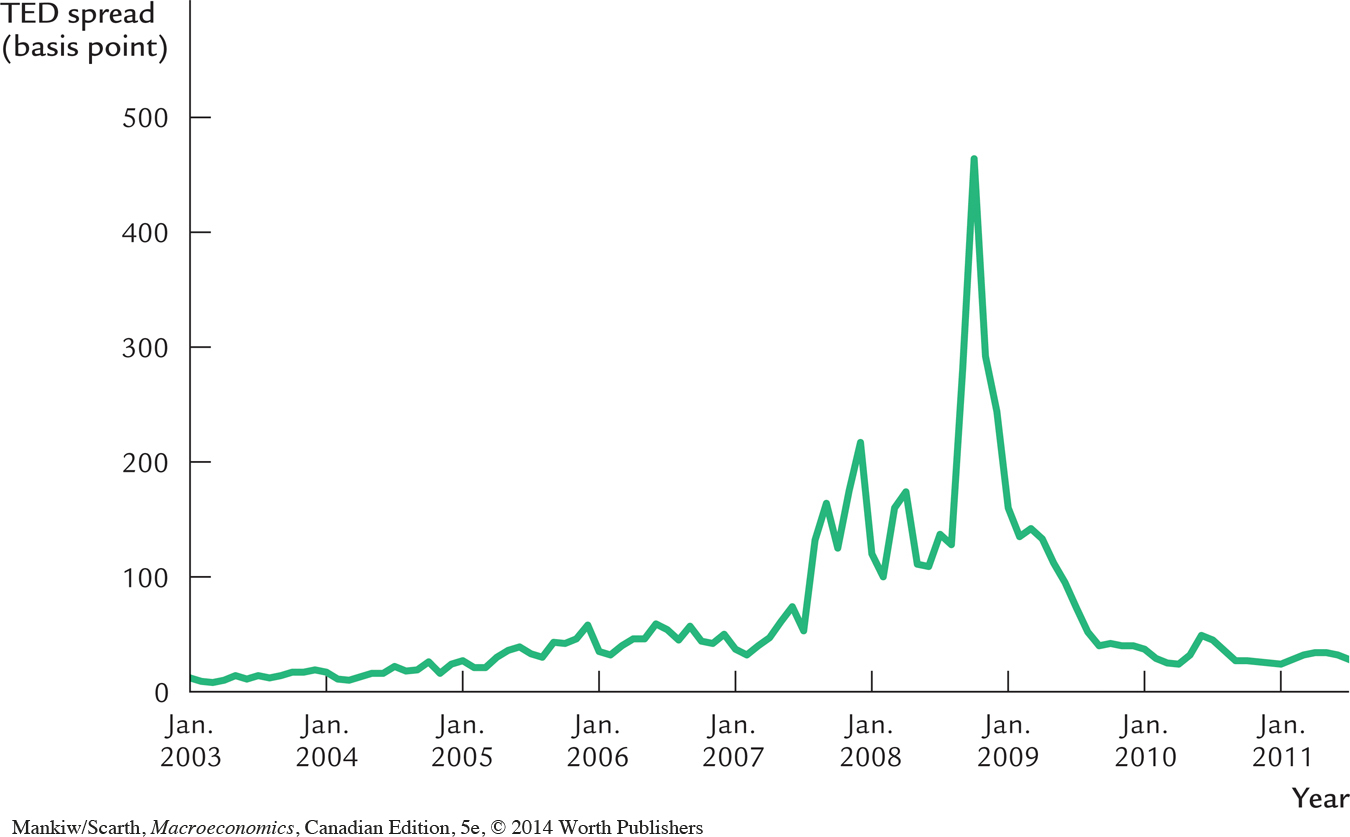

The TED Spread

A common type of indicator of perceived credit risk is the spread between two interest rates of similar maturity. For example, Financially Shaky Corporation might have to pay 7 percent for a one-year loan, whereas Safe and Solid Corporation has to pay only 3 percent. That spread of 4 percentage point occurs because lenders are worried that Financially Shaky might default; as a result, they demand compensation for bearing that risk. If Financially Shaky gets some bad news about its financial position, the interest rate spread might rise to 5 or 6 percentage points or even higher. Thus, one way to monitor perceptions of credit risk is to follow interest rate spreads.

One particularly noteworthy interest rate spread is the so-called TED spread (and not just because it rhymes). The TED spread is the difference between three-month interbank loans and three-month Treasury bills. The T in TED stands for T-bills, and ED stands for EuroDollars (because, for regulatory reasons, these interbank loans typically take place in London). The TED spread is measured in basis points, where a basis point is 1 one-hundredth of a percentage point (0.01 percent). Normally, the TED spread is about 10 to 50 basis points (0.1 to 0.5 percent). The spread is small because commercial banks, while a bit riskier than the government, are still very safe. Lenders do not require much extra compensation to accept the debt of banks rather than the government.

In times of financial crisis, however, confidence in the banking system falls. As a result, banks become reluctant to lend to one another, so the TED spread rises substantially. Figure 20-1 shows the TED spread before, during, and after the financial crisis of 2008–2009. As the crisis unfolded, the TED spread rose substantially, reaching 464 basis points in October 2008, just after the investment bank Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy. The high level of the TED spread is a direct indicator of how worried people were about the solvency of the banking system.

4. Credit Crunch The fourth element of a financial crisis is a credit crunch. With many financial institutions facing difficulties, would-be borrowers have trouble getting loans, even if they have profitable investment projects. In essence, the financial system has trouble performing its normal function of directing the resources of savers into the hands of borrowers with the best investment opportunities.

The tightening of credit was clear during the 2008–2009 financial crisis. Not surprisingly, as banks realized that housing prices were falling and that previous lending standards had been too lax, they started raising standards for those applying for mortgages. They required larger down payments and scrutinized borrowers’ financial information more closely. But the reduction in lending did not just affect home-buyers. Small businesses found it harder to borrow to finance business expansions or to buy inventories. Consumers found it harder to qualify for a credit card or car loan. Thus, banks responded to their own financial problems by becoming more cautious in all kinds of lending.

5. Recession The fifth element of a financial crisis is an economic downturn. With people unable to obtain consumer credit and firms unable to obtain financing for new investment projects, the overall demand for goods and services declines. Within the context of the IS–LM model, this event can be interpreted as a contractionary shift in the consumption and investment functions, which in turn leads to similar shifts in the IS curve and the aggregate demand curve. As a result, national income falls and unemployment rises.

Indeed, the recession following the financial crisis of 2008–2009 was a deep one in the United States. Unemployment rose above 10 percent. Worse yet, it lingered at a high level for a long time. Even after the recovery began, growth in GDP was so meager that unemployment declined only slightly. The unemployment rate was still 8 percent in 2012.

In Canada, the recession was much smaller, primarily because we did not suffer the first two stages of the anatomy. With stiffer regulation on mortgages and banks, we had no housing-price collapse and no insolvencies at financial institutions. There was still some waning of confidence in many firms and among Canadian households, however, given the strong linkages with the American economy. For example, the threatened bankruptcy among car manufacturers in the U.S. had direct implications for the Canadian operations of those firms and those in the wider auto-parts industry. More generally, with so high a proportion of our GDP exported to the United States, a recession there means lower sales for our firms, and Canadian employees worrying about layoffs. Precautionary motives, then, led to a cutting back of consumption and investment spending in Canada, so it was not just the export component of aggregate demand that fell in Canada.

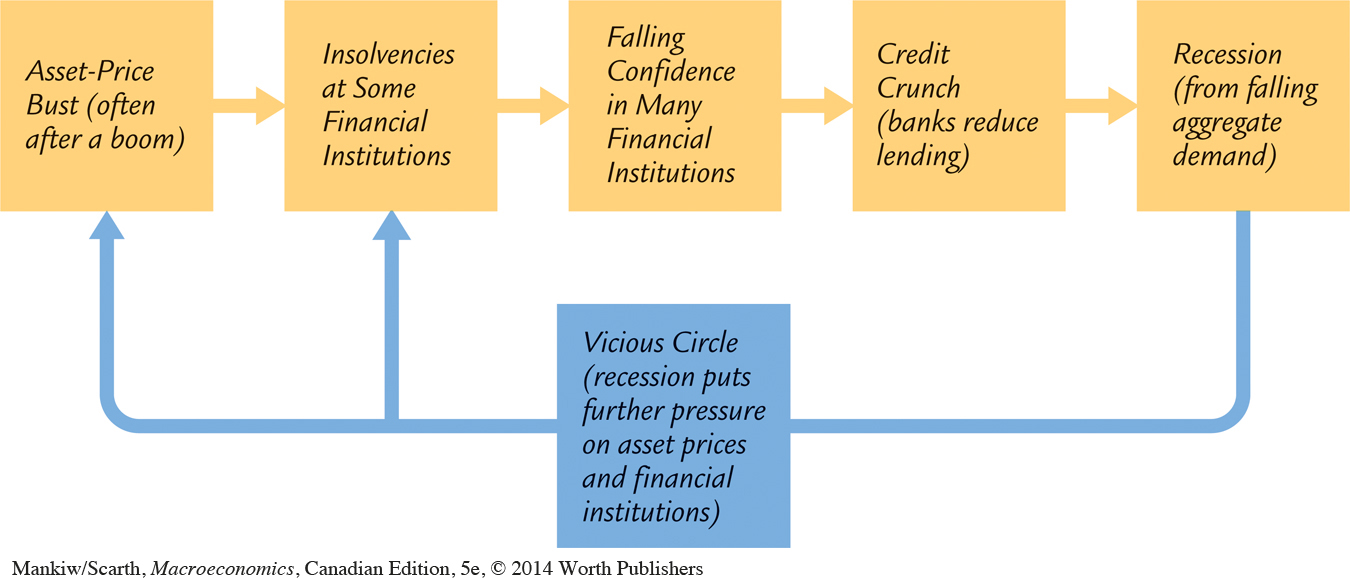

6. A Vicious Circle The sixth and final element of a financial crisis is a vicious circle. The economic downturn reduces the profitability of many companies and the value of many assets. The stock market declines. Some firms go bankrupt and default on their business loans. Many workers become unemployed and default on their personal loans. Thus, we return to steps 1 (asset-price busts) and 2 (financial institution insolvencies). The problems in the financial system and the economic downturn reinforce each other. Figure 20-2 illustrates the process.

In 2008 and 2009, the vicious circle was apparent. Some feared that the combination of a weakening financial system and a weakening economy would cause the economy to spiral out of control, pushing the country into another Great Depression. Fortunately, that did not occur, in part because policymakers were intent on preventing it.

That brings us to the next question: faced with a financial crisis, what can policymakers do?

CASE STUDY

Who Should Be Blamed for the Financial Crisis of 2008–2009?

“Victory has a thousand fathers, but defeat is an orphan.” This famous quotation from John F. Kennedy contains a perennial truth. Everyone is eager take credit for success, but no one wants to accept blame for failure. In the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008–2009, many people wondered who was to blame. Not surprisingly, no one stepped forward to accept responsibility.

Nonetheless, economic observers have pointed their fingers at many possible culprits within the United States. The accused include the following:

The Federal Reserve. The nation’s central bank kept interest rates low in the aftermath of the 2001 recession. This policy helped promote the recovery, but it also encouraged households to borrow and buy housing. Some economists believe by keeping interest rates too low for too long, the Fed contributed to the housing bubble that eventually led to the financial crisis.

Home-buyers. Many people were reckless in borrowing more than they could afford to repay. Others bought houses as a gamble, hoping that housing prices would keep rising at a torrid pace. When housing prices fell instead, many of these homeowners defaulted on their debts.

Mortgage brokers. Many providers of home loans encouraged households to borrow excessively. Sometimes they pushed complicated mortgage products with payments that were low initially but exploded later. Some offered what were called NINJA loans (an acronym for “no income, no job or assets”) to households that should not have qualified for a mortgage. The brokers did not hold these risky loans, but instead sold them for a fee after they were issued.

Investment banks. Many of these financial institutions packaged bundles of risky mortgages into mortgage-backed securities and then sold them to buyers (such as pension funds) that were not fully aware of the risks they were taking on.

Rating agencies. The agencies that evaluated the riskiness of debt instruments gave high ratings to various mortgage-backed securities that later turned out to be highly risky. With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that the models the agencies used to evaluate the risks were based on dubious assumptions.

Regulators. Regulators of banks and other financial institutions are supposed to ensure that these firms do not take undue risks. Yet the regulators failed to appreciate that a substantial decline in housing prices might occur and that, if it did, it could have systemic implications for the financial system.

Government policymakers. For many years, political leaders have pursued policies to encourage homeownership. Such policies include the personal income tax deductibility of mortgage interest in the United States and the establishment of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored enterprises that promoted mortgage lending. Households with shaky finances, however, might have been better off renting. In addition, nine years before the crisis, U.S. lawmakers repealed the regulation that had previously precluded the federally insured banks from being affiliated with investment banks—firms that took the lead in developing such products as the mortgage-backed securities. This policy had the effect of blurring the lines between traditional banks and more risk-oriented institutions, and thereby decreasing the general level of transparency. In retrospect, this legal change constituted an error in policymaking.

In the end, it seems that each of these groups (and perhaps a few others as well) bear some of the blame. As The Economist magazine once put it, the problem was one of “layered irresponsibility.”

Finally, keep in mind that this financial crisis was not the first one in history. Such events, though fortunately rare, do occur from time to time. Rather than looking for a culprit to blame for this singular event, perhaps we should view speculative excess and its ramifications as an inherent feature of market economies. Policymakers can respond to financial crises as they happen, and they can take steps to reduce the likelihood and severity of such crises, but preventing them entirely may be too much to ask given our current knowledge.3

Policy Responses to a Crisis

Because financial crises are both severe and multifaceted, macroeconomic policymakers use various tools, often simultaneously, to try to control the damage. Here we discuss three broad categories of policy responses.

Conventional Monetary and Fiscal Policy As we have seen, financial crises raise unemployment and lower incomes because they lead to a contraction in the aggregate demand for goods and services. Policymakers can mitigate these effects by using the tools of monetary and fiscal policy to expand aggregate demand. The central bank can increase the money supply and lower interest rates. The government can increase government spending and cut taxes. That is, a financial crisis can be seen as a shock to the aggregate demand curve, which can, to some degree, be offset by appropriate monetary and fiscal policy.

American policymakers did precisely this during the financial crisis of 2008–2009. To expand aggregate demand, the Federal Reserve cut its target for the federal funds rate from 5.25 percent in September 2007 to approximately zero in December 2008. It then stayed at that low level for the next three years. In February 2008 President Bush signed into law a $168 billion stimulus package, which funded tax rebates of $300 to $1,200 for every taxpayer. In 2009 President Obama signed into law a $787 billion stimulus, which included some tax reductions but also significant increases in government spending. All of these moves were aimed at propping up aggregate demand.

Similar policy initiatives were undertaken in Canada. The Bank of Canada lowered the overnight lending rate to 1 percent and promised to keep it there for a prolonged period of time, mortgage rules were tightened to avoid a housing-price bubble here, and the Finance Minister introduced a Budget in 2009 involving the biggest deficit in Canadian history.

There are limits, however, to how much conventional monetary and fiscal policy can do. A central bank cannot cut its target for the interest rate below zero. (Recall the discussion of the liquidity trap in Chapter 11.) Fiscal policy is limited as well. Stimulus packages add to the government budget deficit, which is already enlarged because economic downturns automatically increase unemployment-insurance payments and decrease tax revenue. Increases in government debt are a concern in themselves, because they place a burden on future generations of taxpayers and call into question the government’s own solvency.

The limits of monetary and fiscal policy during a financial crisis naturally lead policymakers to consider other, and sometimes unusual, alternatives. These other types of policy are of a fundamentally different nature. Rather than addressing the symptom of a financial crisis (a decline in aggregate demand), they aim to fix the financial system itself. If the normal process of financial intermediation can be restored, consumers and business will be able to borrow again, and the economy’s aggregate demand will recover. The economy can then return to full employment and rising incomes. The next two categories describe the major policies aimed directly at fixing the financial system.

Lender of Last Resort When the public starts to lose confidence in a bank, they withdraw their deposits. In a system of fractional-reserve banking, large and sudden withdrawals can be a problem. Even if the bank is solvent (meaning that the value of its assets exceed the value of its liabilities), it may have trouble satisfying all its depositors’ requests. Many of the bank’s assets are illiquid—that is, they cannot be easily sold and turned into cash. A business loan to a local restaurant, a car loan to a local family, and a student loan to your roommate, for example, may be valuable assets to the bank, but they cannot be easily used to satisfy depositors who are demanding their money back immediately. A situation in which a solvent bank has insufficient funds to satisfy its depositors’ withdrawals is called a liquidity crisis.

The central bank can remedy this problem by lending money directly to the bank. As we discussed in Chapter 19, the central bank can create money out of thin air by, in effect, printing it. (Or, more realistically in our electronic era, it creates a bookkeeping entry for itself that represents those monetary units.) It can then lend this newly created money to the bank experiencing withdrawals and accept the bank’s illiquid assets as collateral. When a central bank lends to a bank in the midst of a liquidity crisis, it is said to act as a lender of last resort.

The goal of such a policy is to allow a bank experiencing withdrawals to weather the storm of reduced confidence. Without such a loan, the bank might be forced to sell its illiquid assets at fire-sale prices. If such a fire sale were to occur, the value of the bank’s assets would decline, and a liquidity crisis could then threaten the bank’s solvency. By acting as a lender of last resort, the central bank stems the problem of bank insolvency and helps restore the public’s confidence in the banking system.

During 2008 and 2009, the Federal Reserve in the United States was extraordinarily active as a lender of last resort. During this crisis, the Fed set up a variety of new ways to lend to financial institutions. And the financial institutions included were not only conventional banks but also so-called shadow banks. Shadow banks are financial institutions that, while not technically banks, serve similar functions. At the time, they were experiencing similar difficulties.

For example, the Fed was willing to make loans to money market mutual funds. Money market funds are not banks, and they do not offer insured deposits. But they are in some ways similar to banks: they take in deposits, invest the proceeds in short-term loans such as commercial paper issued by corporations, and assure depositors that they can obtain their deposits on demand with interest. In the midst of the financial crisis, depositors worried about the value of the assets the money market funds had purchased, so these funds were experiencing substantial withdrawals. The shrinking deposits in money market funds meant that there were fewer buyers of commercial paper, which in turn made it hard for firms that needed the proceeds from these loans to finance their continuing business operations. By its willingness to lend to money market funds, the Fed helped maintain this particular form of financial intermediation.

It is not crucial to learn the details of the many new lending facilities the Fed established during the crisis. Indeed, many of these programs were closed down as the economy started to recover because they were no longer needed. What is important to understand is that these programs, both old and new, have one purpose: to ensure that the financial system remains liquid. That is, as long as a bank (or shadow bank) had assets that could serve as reliable collateral, the Fed stood ready to lend money to the financial institution so that its depositors could make withdrawals.

Injections of Government Funds The final category of policy responses to a financial crisis involves the government using public funds to prop up the financial system.

The most direct action of this sort is a giveaway of public funds to those who have experienced losses. Deposit insurance is one example. But giveaways of public funds can also occur on a more discretionary basis. For example, when two trust companies failed in Alberta in the 1980s, all deposits (even those bigger than the CDC limit) were covered by the government.

Another way for the government to inject public funds is to make risky loans. Normally, when the central bank acts as lender of last resort, it does so by lending to a financial institution that can pledge good collateral. But if the government makes loans that might not be repaid, it is putting public funds at risk. If the loans do indeed default, taxpayers end up losing.

During the financial crisis of 2008–2009, the Fed engaged in a variety of risky lending. In March 2008, it made a $29 billion loan to JPMorgan Chase to facilitate its purchase of the nearly insolvent Bear Stearns. The only collateral the Fed received was Bear’s holdings of mortgage-backed securities, which were of dubious value. Similarly, in September 2008, the Fed lent $85 billion to prop up the insurance giant AIG, which faced large losses from having insured the value of some mortgage-backed securities (through an agreement called a credit default swap). The Fed took these actions to prevent Bear Stearns and AIG from entering a long bankruptcy process, which could have further threatened the financial system. These institutions were regarded as “too big to fail.”

A final way for the government to use public funds to address a financial crisis is for the government itself to inject capital into financial institutions. In this case, rather than being just a creditor, the government gets an ownership stake in the companies. The AIG loans in 2008 had significant elements of this: as part of the loan deal, the government got warrants (options to buy stock) and so eventually owned most of the company. A clearer example is the capital injections organized by the U.S. Treasury in 2008 and 2009. As part of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), the government put hundreds of billions of dollars into various banks in exchange for equity shares in those banks. The goal of the program was to maintain the banks’ solvency and keep the process of financial intermediation intact.

Not surprisingly, the use of public funds to prop up the financial system, whether done with giveaways, risky lending, or capital injections, is controversial. Critics assert that it is unfair to taxpayers to use their resources to rescue financial market participants from their own mistakes. Moreover, the prospect of such financial bailouts may increase moral hazard because when people believe the government will cover their losses, they are more likely to take excessive risks. Financial risk taking becomes “heads I win, tails the taxpayers lose.” Advocates of these policies acknowledge these problems, but they point out that risky lending and capital injections could actually make money for taxpayers if the economy recovers. More important, they believe that the costs of these policies are more than offset by the benefits of averting a deeper crisis and more severe economic downturn.

Policies to Prevent Crises

In addition to the question of how policymakers should respond once facing a financial crisis, there is another key policy debate: how should policymakers prevent future financial crises? Unfortunately, there is no easy answer. But here are four areas where policymakers have been considering their options and, in some cases, revising their policies.

Focusing on Shadow Banks Traditional chartered banks are regulated. One justification is that the government insures some of their deposits through the CDIC. Policymakers have long understood that deposit insurance produces a moral hazard problem. Because of deposit insurance, depositors have no incentive to monitor the riskiness of banks in which they make their deposits; as a result, bankers have an incentive to make excessively risky loans, knowing they will reap any gains while the deposit insurance system will cover any losses. In response to this moral hazard problem, the government regulates the risks that banks take.

Much of the crisis of 2008–2009, however, concerned not traditional banks but rather shadow banks—financial institutions that (like banks) are at the centre of financial intermediation but (unlike banks) do not take in deposits insured by the government. Bear Sterns and Lehman Brothers in the United States, for example, were investment banks and, therefore, subject to less regulation. Similarly, hedge funds, insurance companies, and private equity firms can be considered shadow banks. These institutions do not suffer from the traditional problem of moral hazard arising from deposit insurance, but the risks they take may nonetheless be a concern of public policy because their failure can have macroeconomic ramifications.

Many policymakers have suggested that these shadow banks should be limited in how much risk they take. One way to do that would be to require that they hold more capital, which would in turn limit these firms’ ability to use leverage. Advocates of this idea say it would enhance financial stability. Critics say it would limit these institutions’ ability to do their job of financial intermediation.

Another issue concerns what happens when a shadow bank runs into trouble and nears insolvency. Legislation passed in the United States in 2010, the so-called Dodd-Frank Act, gave the deposit insurance agency authority over shadow banks, much as it already had over traditional chartered banks. That is, the FDIC (the U.S. version of our CDIC) can now take over and close a nonbank financial institution if the institution is having trouble and the FDIC believes it could create systemic risk for the economy. Advocates of this new law believe it will allow a more orderly process when a shadow bank fails and thereby prevent a more general loss of confidence in the financial system. Critics fear it will make bailouts of these institutions with taxpayer funds more common and exacerbate moral hazard.

FYI

CoCo Bonds

One intriguing idea for reforming the financial system is to introduce a new financial instrument called “contingent, convertible debt,” sometimes simply called CoCo bonds. The proposal works as follows: require banks, or perhaps a broader class of financial institutions, to sell some debt that can be converted into equity when these institutions are deemed to have insufficient capital.

This debt would be a form of preplanned recapitalization in the event of a financial crisis. Unlike the bank rescues in 2008–2009, however, the recapitalization would have the crucial advantage of being done with private, rather than taxpayer, funds. That is, when things go bad and a bank approaches insolvency, it would not need to turn to the government to replenish its capital. Nor would it need to convince private investors to chip in more capital in times of financial stress. Instead, the bank would simply convert the CoCo bonds it had previously issued, wiping out one of its liabilities. The holders of the CoCo bonds would no longer be creditors of the bank; they would be given shares of stock and become part owners. Think of it as crisis insurance.

Some bankers balk at this proposal because it would raise the cost of doing business. The buyers of these CoCo bonds would need to be compensated for providing this insurance. The compensation would take the form of a higher interest rate than would be earned on standard bonds without the conversion feature.

But this contingent, convertible debt would make it easier for the financial system to weather a future crisis. Moreover, it would give bankers an incentive to limit risk by, say, reducing leverage and maintaining strict lending standards. The safer these financial institutions are, the less likely the contingency would be triggered and the less they would need to pay to issue this debt. By inducing bankers to be more prudent, this reform could reduce the likelihood of financial crises.

CoCo bonds are still a new and untried idea, but they may offer one tool to guard against future financial crises. In 2011, the European Banking Authority established guidelines for the issuance of these bonds. How prevalent they will become in the future remains to be seen.

Restricting Size The financial crisis of 2008–2009 centred on a few very large financial institutions. Some economists have suggested that the problem would have been averted, or at least would have been less severe, if the financial system had been less concentrated. When a small institution fails, bankruptcy law can take over as it usually does, adjudicating the claims of the various stakeholders, without resulting in economy-wide problems. These economists argue that if a financial institution is too big to fail, it is too big.

Various ideas have been proposed to limit the size of financial firms. One would be to restrict mergers among banks. Another idea is to require higher capital requirements for larger banks. Advocates of these ideas say that a financial system with smaller firms would be more stable. Critics say that such a policy would prevent banks from taking advantage of economies of scale and that the higher costs would eventually be passed on to the bank’s customers.

Reducing Excessive Risk Taking The financial firms that failed in the United States during the financial crisis of 2008–2009 did so because they took risks that ended up losing large sums of money. Some observers believe that one way to reduce the risk of future crises is to limit excessive risk taking. Yet because risk taking is at the heart of what many financial institutions do, there is no easy way to draw the line between excessive and appropriate risks.

Nonetheless, the Dodd-Frank Act included several provisions aimed at limiting risk taking. Perhaps the best known is the so-called Volcker rule, named after Paul Volcker, the former Federal Reserve chairman who first proposed it. Under the Volcker rule, chartered banks are restricted from making certain kinds of speculative investments. Advocates say the rule will help protect banks. Critics say that by restricting the banks’ trading activities, it will make the market for those speculative financial instruments less liquid.

Making Regulation Work Better The financial system is diverse, with many different types of firms performing various functions and having developed at different stages of history. As a result, the regulatory apparatus overseeing these firms is highly fragmented.

After the financial crisis of 2008–2009, policymakers tried to improve the U.S. system of regulation. The Dodd-Frank Act created a new Financial Services Oversight Council, chaired by the Secretary of Treasury, to coordinate the various regulatory agencies. It also created a new Office of Credit Ratings to oversee the private credit rating agencies, which were blamed for failing to anticipate the great risk in many mortgage-backed securities. The law also established a new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, with the goal of ensuring fairness and transparency in how financial firms market their products to consumers. Only time will tell whether this new regulatory structure works better than the old one.

CASE STUDY

Did Recent Practice in Macroeconomic Policy Contribute to the Financial Crisis?

The answer to this question is: to some extent “Yes,” even though policy for the previous 15 years contributed toward our having a prolonged period that involved both low inflation and low unemployment. Why? Because the warning of a long-standing but ignored critic of mainstream macroeconomics (Hyman Minsky) has proved accurate. In an odd turn of phrase, Minsky stressed that “stability is destabilizing.”

Without attributing their views to Minsky, macroeconomists seem to have accepted this warning—regarding fiscal policy—years ago. But it took the financial crisis for us to more fully appreciate its applicability to monetary policy.

Let us review our experience with fiscal policy. Western governments reacted to the experience of the Great Depression by committing themselves in 1945 to use budget policy to combat rising unemployment whenever required. It was not recognized at the time that this commitment led to a change in the institutions of wage negotiation. The laissez faire approach to recessions was simply to wait for unemployed individuals to cut their wages by whatever it took to reacquire a job. The Keynesian (and the government’s) view was that wages fall too slowly for the classical position to be embraced. Hence, the government stepped in to increase firms’ demand for labour at the existing level of wages. The problem was that this commitment made it irrational for workers to ever lower their wages, making government involvement ever more required in the future. Inevitably, this unexpected (but in retrospect not surprising) change in wage-setting behaviour forced governments to run ever larger budget deficits as the need for their ongoing involvement became entrenched. It took 35 years for governments to back away at least partially from this commitment to full employment. For example, President Reagan in the United States won a showdown with the air traffic controllers and Prime Minister Thatcher in the United Kingdom did likewise with coal miners, to convince their citizens that there would actually be costs to be borne if they insisted upon wage levels that were not backed up by productivity.

A similar lesson emerged in our experience with monetarism in the 1980s. Western central banks picked a particular traditional definition of the money supply (the total of currency outside banks plus the public’s demand deposits at banks—called M1) to control. The theory was that—since macroeconomists had estimated that the public’s demand for M1 had been a stable function of just a few variables for many years—the central bank could control inflation (the growth in the money prices of goods) by limiting the issue of M1. But when chartered banks wanted more reserves to facilitate more lending and they could no longer get more M1 to accomplish this, they simply invented substitutes for M1 (such as developing overnight lending markets). This time Minsky’s prediction of institutional change was in the financial sector (a permanent decrease in demand for M1).

Despite these earlier experiences, the recent commitment in monetary policy to deliver a very low and stable inflation rate was not seen by many as anything that might foster undesirable institutional change. But we now know that we should have expected as much—especially since (even back in 1987) Minsky predicted that securitization (which he fully described back then) would get invented.

The problem with monetary policy being pretty successful in limiting volatility and business cycles is that people get complacent. They forget that problems have always developed when people become overconfident and take on too much debt. Similarly, firms raise their debt–equity ratios (get more highly leveraged) in an attempt to keep up with their more aggressive competitors. The lessons of history seem ever more remote, and this convinces households to embrace more risk taking too. With low inflation, interest rates are low too, and this is discouraging for patient and prudent households who fall behind others who purchase riskier assets. In short, a period of stability leads to an increased willingness to take on risk. This raises the demand for people to invent new financial products that deliver higher returns with seemingly almost no additional risk. And it induces financial advisors to sell these products to avoid losing clients to others that are delivering higher returns. So even if there were not a weakening of regulation, or such developments such as globalization, skill-biased technical change, and a waning of unions (all developments that made it hard for middle-class households to maintain earlier living standards) there would have been (as there always is during stable times with low interest rates) an increased taking on of debt and risk.

One of the reasons why this invention of new financial products proceeds at such a pace is that those in the financial industry have faced a “heads I win, tails I don’t lose” opportunity. They have known that—despite the partial backing off in the 1980s—the government can still be counted on to have a commitment to limiting unemployment. This meant that the banking system—which facilitates all the transactions in the real economy—could not be allowed to fail. In short, the government and its central bank was known to be stuck with having to bail out irresponsible behaviour among banks.

This diagnosis leads us to the question: How can the government support the banking system and simultaneously—and credibly—claim that they will not be forced to “give in” and bail out the “bad guys?” The CoCo Bonds suggestion is one answer. UCLA economist Roger Farmer has offered a second appealing suggestion. He suggests creating a mutual fund which holds common shares in the banks (in proportion to their size in the market). The central bank could buy a number of shares in this mutual fund (financed by selling three-month bonds that are fully guaranteed by the government, so that these purchases would not cost the taxpayer). In a financial crisis, the central bank could commit to buy more shares in the fund—at a price of (say) $15, when the current price was just $10. The fund managers would have to place these incoming funds by purchasing private bank shares. They would buy the reliable ones, not the failing ones, and it would be private market participants (not the government) that would be making these judgments. Deposit insurance would protect depositors in all banks, but the outcome of these selective share purchases would limit the recapitalization of banks to just the deserving ones. The banking system would be preserved, but some individual bank owners (as opposed to the depositors) would be allowed to sustain losses and fail. So the Scandinavian outcome to their banking crisis in 1992 would emerge, not the Japanese outcome to their banking troubles of the last couple of decades. The limiting of the support to just the “good guys” is what would give the government credibility when it claimed that it would not fall prey to the “too big to fail” problem in the future. This is the fundamental challenge: we need institutional change that can make it credible for the government to simultaneously protect depositors and bank creditors, while at the same time not reward bad behaviour—despite their caring about unemployment.

Suggestions like Roger Farmer’s always sound a bit far-fetched when they are first proposed. But by appreciating the analogy with tradable emission permits—first proposed by economists and met with skepticism in the 1960s, but now widely recognized as making a major positive contribution to pollution abatement—we can see that Farmer’s suggestion should be seriously considered.

The problem with the traditional approach to pollution control—such as an edict that all firms must cut back by 20 percent—is that some firms do not know how to continue to produce at all if they have to meet that edict. There is an incentive for all firms to claim that they are in that position, so they deluge the government with requests for exemptions. They realize that the government cannot know who is dissembling and that the government very much fears the resulting layoffs if the firms’ predictions are true. So, many exemptions and postponements are granted and little progress on reducing emissions occurs. With the tradable emission permits, however, the government no longer has to grant exemptions. It simply invites the protesting firms to purchase a permit on the open market. So the firms self-select into the cutting-back group and the permit-purchasing group. The government reaches the system-wide abatement target without its credibility (and therefore the effectiveness of the program) being undermined by its caring about unemployment. A large payoff awaits if we can work out the applied details as we try to exploit this pollution-abatement analogy in reforming how we might “bail out” the financial sector in the future.

CASE STUDY

The European Sovereign Debt Crisis

In 2012, many of the nations of Europe were struggling to prevent a financial crisis. The problem stemmed from sovereign debt—that is, debt issued by governments. For many years, banks and bank regulators had treated such debt as risk-free. The central governments of Europe, they presumed, would always honour their obligations. Because of this belief, these bonds paid a lower interest rate and commanded a higher price than they would have if they had been perceived as less reliable credit risks.

In 2010, however, financial market participants started to doubt that this optimism about European governments was warranted. The problem began with Greece. In 2010, Greek debt (net financial liabilities) had increased to 116 percent of its GDP, compared to a European average of 58 percent. Moreover, it seemed that for years Greece had been misreporting the state of its finances and that it had no plan to rein in its soaring debts. In April 2010, Standard & Poor’s reduced the rating on Greek debt to junk status, indicating a particularly poor credit risk. Because many feared that default was likely, the prices of Greek debt fell, and the interest rate that Greece had to pay on new borrowing rose markedly. By the summer of 2011, the interest rate on Greek debt was 26 percent. In November of that year, it rose to over 100 percent.

European policymakers were concerned that problems in Greece could have repercussions throughout Europe. Many European banks held Greek debt among their assets. As the value of Greek debt fell, the banks were pushed toward insolvency. A Greek default could push many banks over the edge, leading to a broader crisis in confidence, a credit crunch, and an economic downturn.

As a result, policymakers in healthier European economies, such as Germany and France, helped arrange continuing loans to Greece to prevent an immediate default. Some of these loans were from the European Central Bank, which controls monetary policy in the euro area. This policy move was not popular. Voters in Germany and France wondered why their tax dollars should help rescue the Greeks from their own fiscal profligacy. Voters in Greece, meanwhile, were also unhappy because these loans came with the conditions that Greece drastically cut government spending and raise taxes. These austerity measures led to rioting in Greek streets.

Making matters worse was that Greece was not the only country with such problems. If Greece was allowed to default, rather than being bailed out by its richer neighbours, some feared that Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Italy would be close behind. A widespread decline in the value of the sovereign debt of all these nations would surely put serious strains on the European banking system. And since the world’s banking systems are highly interconnected, it would put strains on the rest of the world as well.

How this situation would play out was not clear. In 2012, it was clear that Greece would not repay all its creditors in full. Negotiations were under way among European leaders regarding how much Greece would pay on its debts and how much its richer neighbours would contribute to help solve its fiscal problems.

CASE STUDY

Will Governments in North America Go the Way of the Indebted European Governments?

Many individuals fear that the United States government may soon replicate the Greek experience, since political dysfunction in Washington suggests that stopping the rise in the government debt-to-GDP ratio may not be possible. Of course, Americans have an additional degree of freedom since their currency serves as the main international medium of exchange. As a result, other countries seem content to accumulate holdings of U.S. dollars and U.S. government debt. But this degree of freedom has allowed Americans to get used to “living beyond their means,” so it may well take them some time to address their over-spending habit. Indeed, a book entitled The Clash of Generations, published in 2012, predicts major upheaval (including serious inflation as the American government partially defaults on its debt by reducing it real value through inflation). This upheaval within our major trading partner would certainly cause some disruption for Canadians, but luckily our government finances are not in such dire shape.

In Chapter 16, we discussed in some detail how the Canadian federal government is well on its way to reducing its debt-to-GDP ratio by almost 50 percentage points over a 25-year period. In addition, our federal government has adjusted the details of our public pension systems to ensure that they are actuarially sound in the face of the aging population (the retirement of the large baby-boom cohort). The Parliamentary Budget Office has concluded that the federal government finances are fully sustainable, and their calculations rely on the very equations that were explained earlier in this text. The Parliamentary Budget Office has calculated what adjustment in the primary deficit is needed today if the government’s debt ratio in 75 years is to be the same as it is today, given their projections concerning future values for the interest rate, the growth rate, and the costs of financing ongoing programs (such as public pensions, employment insurance, health care). These projections are fed into these two equations, working back from the future to the present, and the necessary value for (g – t) is compared to the government’s current actual value of (g – t). If the former is smaller than the latter, fiscal policy is said to be not sustainable. These calculations suggest that the federal government’s finances are sustainable since it could afford to increase its primary deficit today by 1.3 percentage points of GDP and still be at the edge of sustainability.

But one important adjustment that federal authorities have made to achieve this sustainability is that they are limiting future transfer payments to provinces for health care expenditures. Similar analyses applied at the provincial level (for example, by the Auditor General, the Parliamentary Budget Office, CD Howe Institute researchers) all conclude that provincial fiscal policy is not sustainable. Taken as a group, the provinces need either to raise their tax-to-GDP ratio or to lower their program-spending-to-GDP ratio by 2.5 percentage points to achieve sustainability. Rough calculations for Ontario can serve as an example to explain the magnitude of the challenge. We cannot reasonably expect the GDP to grow more than 4 percent annually in nominal terms over the coming years (2 percent productivity growth and 2 percent inflation). Without tax rate increases, then, Ontario government revenues cannot grow more than 4 percent annually. Experience shows that—even without the aging of the baby boomers—we have been unable to keep health care expenditures from growing any less than by 6 percent per year. Since health care represents roughly half of the Ontario government’s spending, a 6 percent growth rate for that item on that item means that—to avoid ever-rising tax rates, the spending on all other programs must be held to a 2 percent growth rate. If these government programs are to be maintained in real terms, this means that workers in these fields (such as teachers) cannot ever expect any increase in real wages! So, while many of the nations in the western world would love to have their fiscal houses in as good shape as ours, even in Canada we face serious budgetary challenges as our population ages.4