Instructions

Click the forward and backward arrows to navigate through the slides. You may also use the Outline menu to skip directly to a slide. Students must complete the slides in order.

Slide 1, Introduction

Fake news, which has dominated the real news headlines in recent years, is unfortunately about as old as the United States itself, which is where it got its start—not surprisingly, with politics.

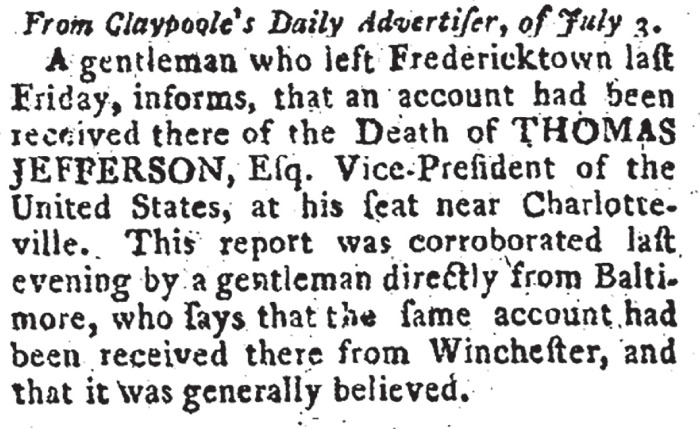

The presidential election of 1800 pitted two bitter rivals against each other: incumbent president John Adams of the Federalist Party (whose members included George Washington and Alexander Hamilton) and his challenger, Vice President Thomas Jefferson of the Democratic-Republican Party (whose members included James Madison and Aaron Burr).Footnote 1

As we discussed in Chapter 8, many of America’s earliest newspapers were part of either the commercial press, which catered to the merchant class, or the partisan press, which fervidly argued for the platform of the political party that subsidized the paper. Predictably, it was the partisan press that resorted to fake news—intentional disinformation in this case, which is false or misleading information spread knowingly by people with malicious intent (see Chapter 2). As the presidential campaign of 1800 grew more heated, some Federalist newspapers, allied with Adams, began to publish stories that Jefferson had died.Footnote 2 Eventually the truth came out in rival newspapers that he was alive and well—although it took time to spread the word, given the very slow pace of newspaper distribution by mail at the time—and Jefferson ultimately won the election.

Fast-forward to the 1830s, when another kind of fake news emerged. At that time, penny press papers (costing one cent) were a new form of journalism that targeted a mass readership, standing in contrast to the more expensive and narrowly focused six-cent partisan and commercial newspapers then in circulation.

The first notable penny press newspaper was the New York Sun , founded in 1833 by twenty-three-year-old printer Benjamin Day. Day’s attempts to reach mass working-class audiences included such innovations as publishing human-interest stories that highlighted crime and scandal, and hiring newsboys to hawk newspapers on the street by shouting out headlines. His paper became New York’s biggest, and he was soon contending with competing penny press start-ups intent on grabbing market share.

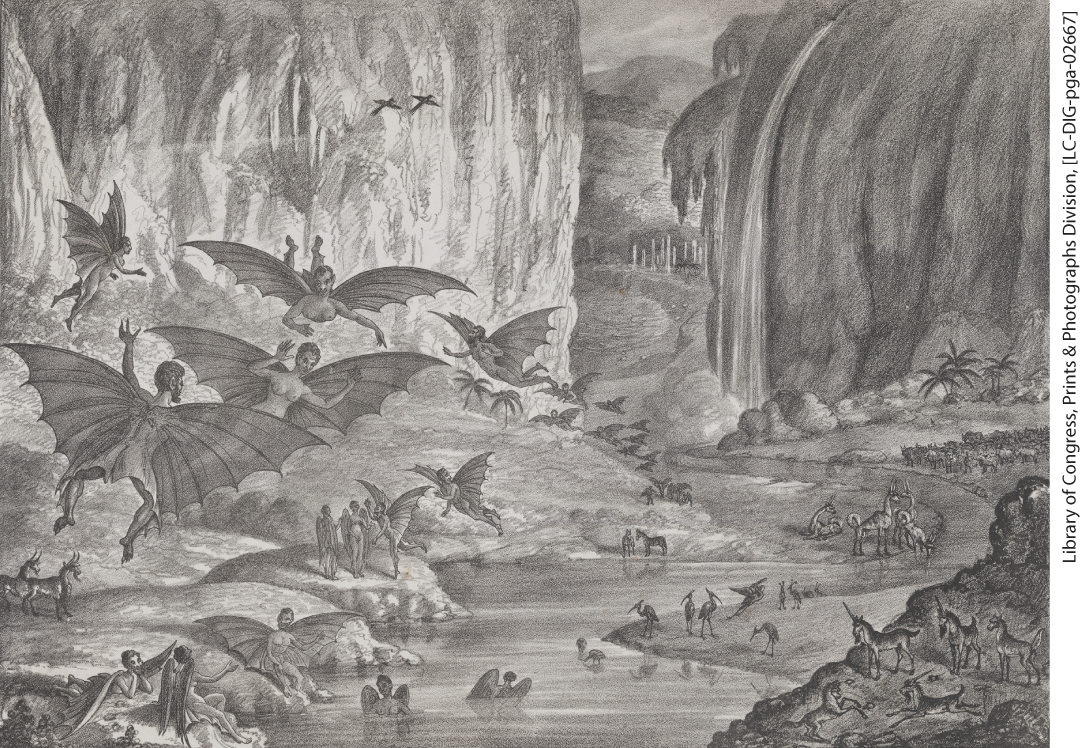

To help keep up with the demand for enticing news stories and outperform the competition, in 1835 Day hired writer Richard Adams Locke, who had arrived from England just a few years earlier. Locke had great success with his first story for the Sun, which focused on a long, lurid murder trial. Next, he wanted to write an even bigger story. Locke, who had a decent scientific acumen, was both fascinated and annoyed by some contemporary scientists who theorized that life and civilizations existed on the moon. He decided to satirize their way of thinking by writing a compelling account of life on the moon, concocting a made-up species of moon dwellers called “man-bats.”

Beginning on August 25, 1835, the Sun ran a series of six articles describing a lunar Eden, complete with oceans, mountains, waterfalls, and cities featuring columned temples and coliseums.Footnote 3 Populating this lunar landscape were familiar and fantastic lunar beasts, including sheep, unicorns, beaver-like creatures on two legs, and four-legged giraffe-like creatures. The most sensational moon creatures, though, were the highest-order beings—flying families of Vespertilio-homo, Locke’s pseudo-scientific Latin name for man-bats. The Sun described them this way: “They averaged four feet in height, were covered, except on the face, with short and glossy copper-colored hair, and had wings composed of a thin membrane, without hair, lying snugly upon their backs, from the top of their shoulders to the calves of their legs.”Footnote 4

Locke anonymously wrote the series but attributed the “Great Astronomical Discoveries” he described therein to a mix of real and fake elements. The discoveries were purportedly made by Sir John Herschel (a real astronomer of the time, whose father, also an astronomer, discovered Uranus) through his new hydro-oxygen telescope (which sounded somewhat believable but didn’t exist) at the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa (a real place, where Herschel did indeed have an observatory), as reported in a supplement to the Edinburgh Journal of Science (a real journal but one that had ceased publication in 1832).Footnote 5

The Sun’s series, now known as “the Great Moon Hoax,” consumed New Yorkers, and news of it spread to the Midwest. But after the series ended and suspicions grew that the story was fake, it drew sharp criticism from James Gordon Bennett, editor of the competing New York Herald, who wrote, “When that paper in order to get money out of a credulous public, seriously persists in averting its truth, it becomes highly improper, wicked, and in fact a species of impudent swindling.”Footnote 6

The Sun’s satire-turned-hoax emerged at a time when others were also playing on Americans’ hopes, dreams, and gullibility. In that same year of 1835, a young P. T. Barnum created an exhibition featuring Joice Heth, an approximately 80-year-old Black woman who Barnum claimed was the 161-year-old nurse of George Washington. Thus began a long career for Barnum in exhibiting human beings he referred to as “curiosities” and bringing his masterful (and sometimes demeaning) promotional skills to traveling circuses and sideshows. The events of the 1800 election and the 1835 Great Moon Hoax are some of the earliest examples of fake news in the United States and demonstrate a tendency on the part of the media, politicians, and other performers to deceive the public—a tendency that has not abated as the country has grown older.