Understanding Western Society

Printed Page 77

Chapter Chronology

Households and Work

In sharp contrast with the rich intellectual and cultural life of Periclean Athens stands the simplicity of its material life. The Athenians, like other Greeks, lived with comparatively few material possessions in houses that were rather simple. Well-to-do Athenians lived in houses consisting of a series of rooms opening onto a central courtyard. Artisans often set aside a room to use as a shop or work area. Larger houses often had a dining room at the front where the men of the family ate and entertained guests at drinking parties called symposia, and a gynaeceum (also spelled gynaikeion), a room or section at the back where the women of the family and the female slaves worked, ate, and slept. Other rooms included the kitchen and bathroom. By modern standards there was not much furniture.

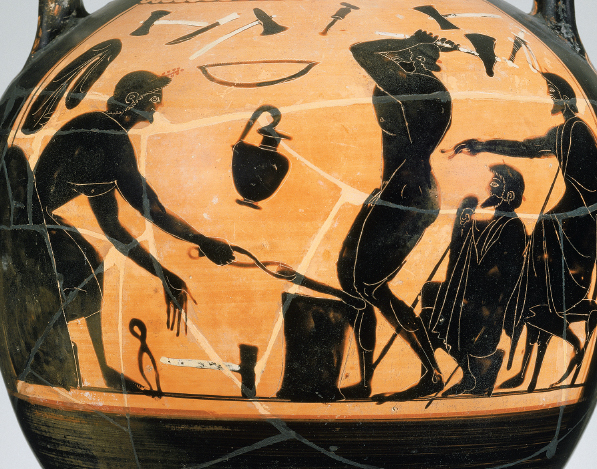

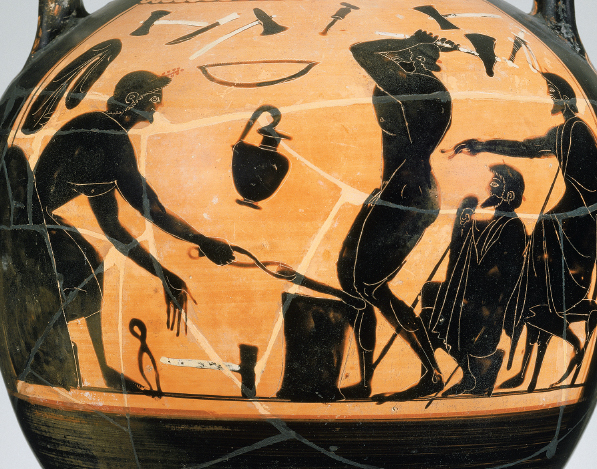

Blacksmith’s ShopThis painting on the side of an amphora from around 500 B.C.E. shows a blacksmith’s shop, with the smiths working and other men providing advice. Men often gathered in artisans’ shops or on the public square to chat, while women’s conversations took place in the home. Although blacksmithing is hot work, a smith would not normally have worked in the nude; showing him naked allowed the painter to demonstrate his ability to depict human musculature. (The Plousios Painter, two-handled jar [amphora]. Greek, Late Archaic Period, about 500–490 B.C.E. Place of Manufacture: Greece, Attica, Athens. Ceramic, Black Figure. Height: 36.1 cm [14 3/16 in.]; diameter: 25.9 cm [10 3/16 in.]. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Henry Lillie Pierce Fund, 01.8035. Photograph © 2013 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Cooking, done over a hearth in the house, provided welcome warmth in the winter. Baking and roasting were done in ovens. Meals consisted primarily of various grains, especially wheat and barley, as well as lentils, olives, figs, grapes, fish, and a little meat. The Greeks used olive oil for cooking, and also as an ointment and as lamp fuel.

In the city a man might support himself as a craftsman — a potter, bronze-smith, sailmaker, or tanner — or he could contract with the polis to work on public buildings. Certain crafts, including spinning and weaving, were generally done by women who produced cloth for their own families and sold it. Men and women without skills worked as paid laborers but competed with slaves for work.

Slavery was commonplace in Greece, as it was throughout the ancient world. Slaves were usually foreigners and often “barbarians,” people whose native language was not Greek. Most citizen households in Athens owned at least one slave. Slaves in Athens ranged widely in terms of their type of work and opportunities for escaping slavery. Some male slaves were skilled workers or well-educated teachers and tutors of writing, while others were unskilled laborers in the city, agricultural workers in the countryside, or laborers in mines. Female slaves worked in agriculture or as domestic servants and nurses for children. Slaves received some protection under the law, and those who engaged in skilled labor for which they were paid could buy their freedom. A few ex-slaves even became Athenian citizens.