Understanding Western Society

Printed Page 158

INDIVIDUALS IN SOCIETY

Bithus, a Soldier in the Roman Army

Citizenship and service in the military have long been linked. In classical Athens, the hoplites, who were the backbone of Athenian armies, were all citizens (see Chapter 3). In the United States today, noncitizens serving on active duty in the armed forces may apply for citizenship immediately instead of having to wait the five years that are normally required for civilian noncitizen residents. Citizenship and army service were also connected in the Roman Empire. Only Roman citizens could be members of the Roman legions, but expanding and defending the empire required huge numbers of troops. These were provided by auxiliary units, which were open to all. Some men were drafted into the auxiliaries, but more joined voluntarily, attracted by the offer of pay and by the promise that, at the end of their service and if they survived, they would be awarded Roman citizenship, which would give them legal, social, and economic privileges.

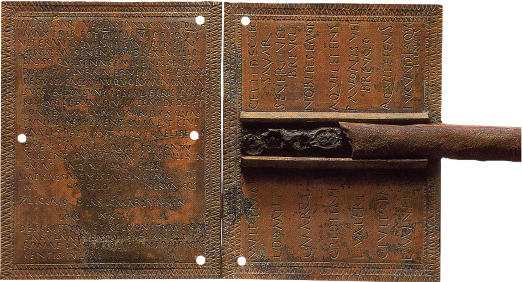

A man’s record of army service and his status as a citizen were recorded on what is known as a military diploma, two bronze sheets about the size of a paperback book wired together on which his military career was set out in an inscription. The names of witnesses were also inscribed on the diploma, and their seals attached, which made the document official. One copy of this diploma stayed in Rome, and one was sent to the soldier himself, much as members of the military today receive discharge papers. Most of these diplomas were melted down long ago and their metal was put to other uses, but about a thousand survive. They provide an exact date, which is very rare in ancient sources, so they can be used to trace the movements of units and many other aspects of the military. They also include details about the lives of ordinary soldiers that are unavailable in any other type of source.

One such soldier was the infantryman Bithus, who was born in Thrace in the northeastern region of modern Greece, part of the empire that provided many troops. He joined an auxiliary unit of the Roman army in 63 C.E. and began with basic training, during which he learned to march and to use the standard weapons of a heavily armed infantryman. His training completed, Bithus was sent to Syria, where he spent most of his career. He was one of the thousands of soldiers sent to this area from all parts of the empire because of the revolt in Judaea. There he met others from as far west as Gaul and Spain, from northern Africa, and from other parts of Greece and the Balkans. Unlike many other units that were shifted periodically, his remained in the same area. While in the army, he raised a family, much like soldiers today. The sons of soldiers like Bithus often themselves joined the army, indicating that soldiers’ families were a fruitful source for recruitment. After twenty-

The example of Bithus is important not because he is unusual but because he is typical. The might of the Roman Empire depended on hundreds of thousands of men just like him, who joined the army for the pay and the promise of a better life that it offered.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- Why would it have been important for a soldier like Bithus to have a permanent record of his military career and status as a citizen?

- Why did — and does — the promise of citizenship serve as an effective recruiting tool for the armed forces?

Source: Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, vol. 16, no. 35 (Berlin: G. Reimer, 1882).

ONLINE DOCUMENT PROJECT

How did the Roman Empire turn countless individuals like Bithus into the most powerful fighting machine the Mediterranean world had ever seen? Keeping the question above in mind, examine documents on the military’s role in the expansion of the empire, and then complete a writing assignment based on the evidence and details from this chapter.

See Document Project for Chapter 6.