Understanding Western Society

Printed Page 475

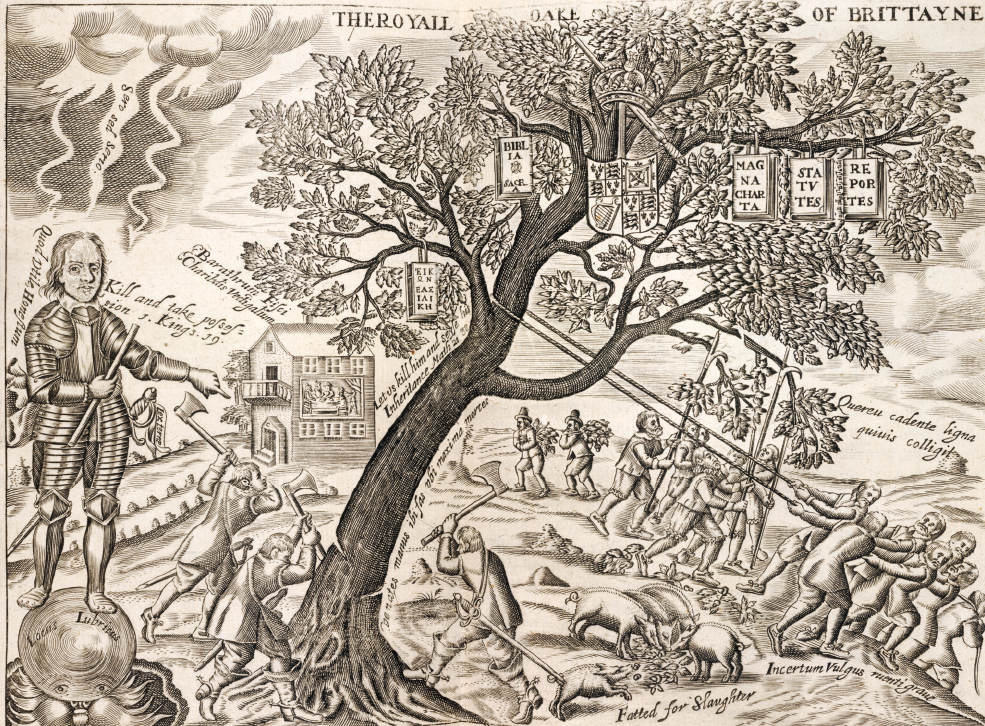

Cromwell and Puritanical Absolutism in England

With the execution of Charles, kingship was abolished. In its place, Oliver Cromwell and his supporters enshrined a commonwealth, or republican government, known as the Protectorate. Theoretically, legislative power rested in the surviving members of Parliament, and executive power was lodged in a council of state. In fact, the army controlled the government, and Oliver Cromwell controlled the army, ruling what was essentially a military dictatorship.

The fiction of republican government was maintained until 1655 when, after repeated disputes, Cromwell dismissed Parliament. Cromwell continued the standing army and proclaimed quasi-

Cromwell had long associated Catholicism in Ireland with sedition and heresy, and led an army there to reconquer the country in August 1649. In the wake of Cromwell’s invasion, the English banned Catholicism in Ireland, executed priests, and confiscated land from Catholics for English and Scottish settlers. These brutal acts left a legacy of Irish hatred for England.

Cromwell adopted mercantilist policies similar to those of absolutist France. He enforced a Navigation Act (1651) requiring that English goods be transported on English ships. The act sparked a short but successful war with the commercially threatened Dutch. While mercantilist legislation ultimately benefited English commerce, for ordinary people, the turmoil of foreign war only added to the harsh conditions of life induced by years of civil war.

The Protectorate collapsed when Cromwell died in 1658 and his ineffectual son succeeded him. Fed up with military rule, the English longed for a return to civilian government and, with it, common law and social stability. By 1660, they were ready to restore the monarchy.