Understanding Western Society

Printed Page 743

The World Market

Commerce between nations has always stimulated economic development. In the nineteenth century, Europe directed an enormous increase in international commerce. Great Britain took the lead in cultivating export markets for its booming industrial output, as British manufacturers looked first to Europe and then around the world.

Take the case of cotton textiles. By 1820, Britain was exporting 50 percent of its production. Europe bought 50 percent of these cotton textile exports, while India bought only 6 percent and had its own well-

In addition to its dominance in the export market, Britain was also the world’s largest importer of agricultural products, raw materials, and manufactured goods. Under free-

International trade grew as transportation systems improved. European investors funded much of the railroad construction undertaken in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, which connected seaports with resource-

The power of steam revolutionized transportation by sea as well as by land. Steam power began to supplant sails on the oceans of the world in the late 1860s. The time needed to cross the Atlantic dropped from three weeks in 1870 to about ten days in 1900, and the opening of the Suez and Panama Canals (in 1869 and 1914, respectively) shortened transport time to other areas of the globe considerably.

The revolution in land and sea transportation encouraged European entrepreneurs to open up and exploit vast new territories around the world. Improved transportation enabled Asia, Africa, and Latin America to ship not only familiar agricultural products but also new raw materials for industry, such as jute, rubber, cotton, and coconut oil. The export of raw materials supplied by these “primary producers” to Western manufacturers boosted economic growth in core countries but did little to establish independent industry in the nonindustrialized periphery.

New communications systems were used to direct the flow of goods across global networks. Transoceanic telegraph cables, firmly in place by the 1880s, enabled rapid communications among the financial centers of the world. The same communications network conveyed world commodity prices instantaneously.

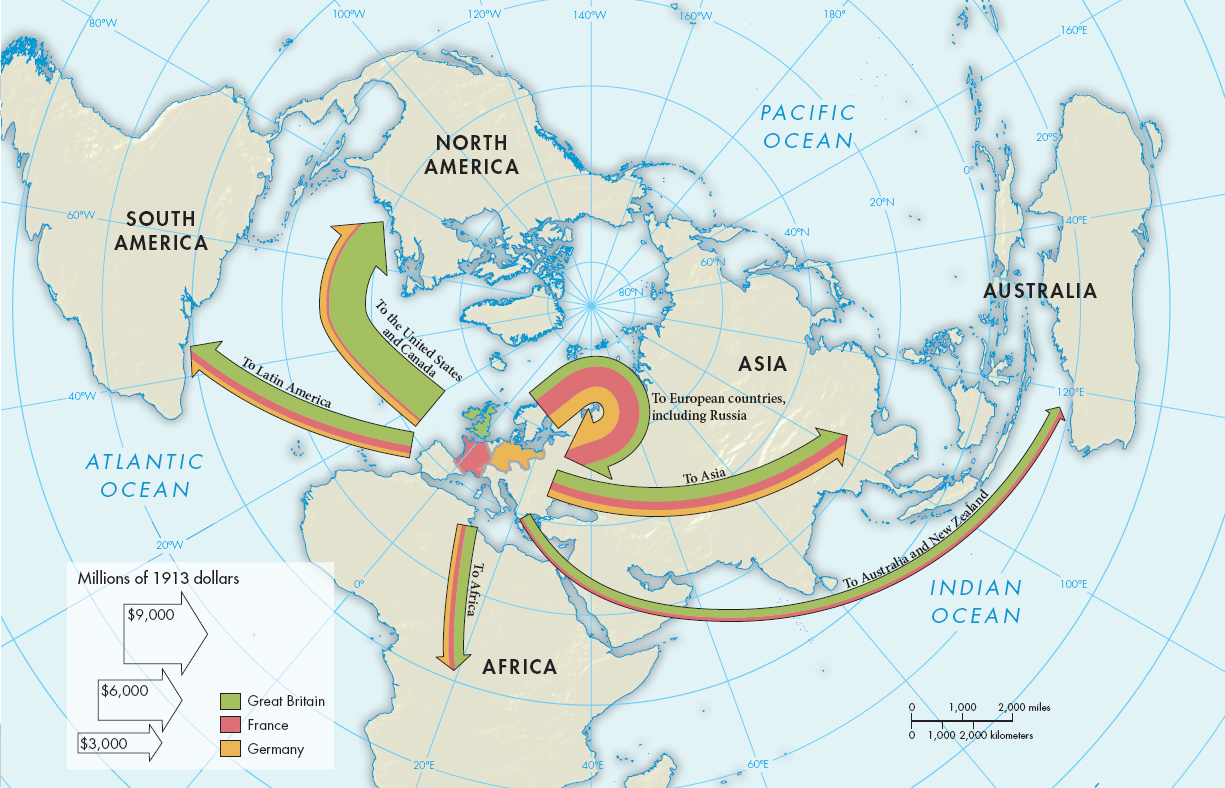

As their economies grew, Europeans began to make massive foreign investments beginning about 1840. By the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Europeans had invested more than $40 billion abroad (Map 24.1). The great gap between rich and poor within Europe meant that the wealthy and moderately well-

About three-

The extension of Western economic power and the construction of neo-