A History of Western Society: Printed Page 328

LIVING IN THE PAST

Treating the Plague

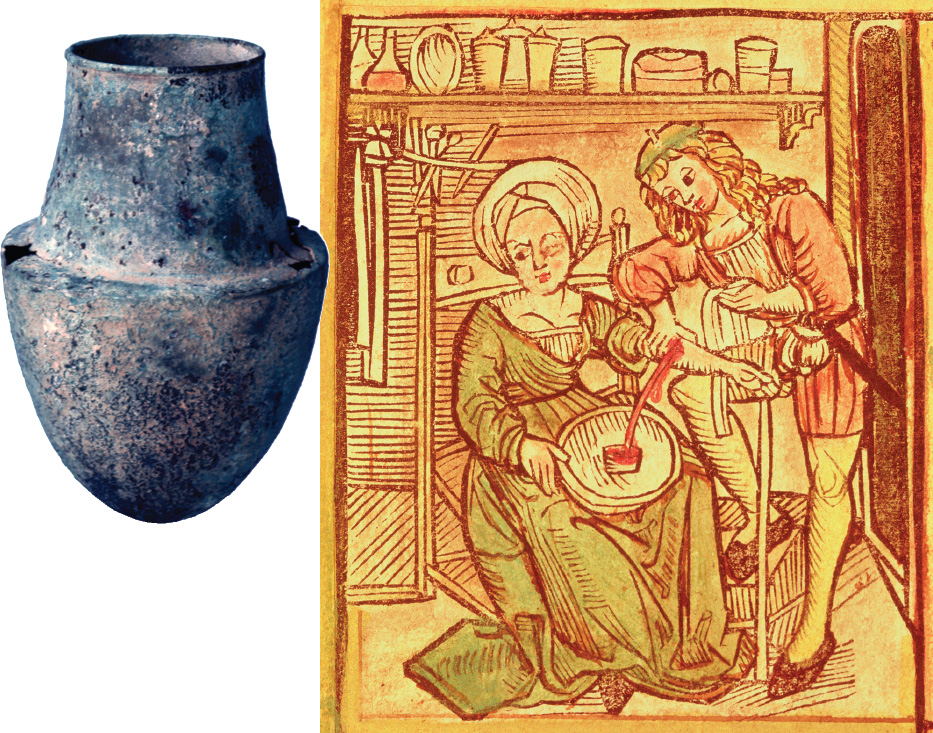

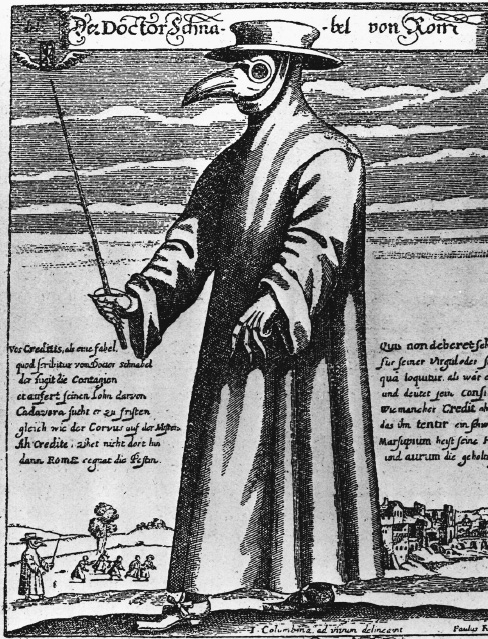

Medieval physicians based treatments for the plague on their understanding of how the body worked, as do doctors in any era. Fourteenth-century people — lay, scholarly, and medical — attributed the disease to “poisons” in the air that caused the fluids in the body to become unbalanced. The imbalance in fluids led to illness, an idea that had been the core of Western ideas about the primary cause of disease since the ancient Greeks. Certain symptoms of the plague, such as boils that oozed and blood-filled coughing, were believed to be the body’s natural reaction to too much fluid.

Doctors thus recommended preventive measures that would block the poisoned air from entering the body, such as burning incense or holding strong-smelling herbs or other substances, like rosemary, juniper, or sulfur, in front of the nose. Treatment concentrated on ridding the body of poisons and bringing the fluids into balance. As one fifteenth-century treatise put it, “everyone over seven should be made to vomit daily” and twice a week wrap up in sheets to “sweat copiously.” The best way to regain health, however, was to let blood: “as soon as [the patient] feels an itch or pricking in his flesh [the physician] must use a goblet or cupping horn to let blood and draw down the blood from his heart, and this should be done two or three times at intervals of one or two days at the most.” Letting blood was considered the most effective way to rebalance the fluids and to flush the body of poisons.

Source: Quotations from Rosemary Horrox, The Black Death (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994), p. 194.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

Question

In the background of the plague doctor engraving, the artist shows a group of children running away as the plague doctor approaches. What aspects of his appearance or treatment methods contributed to this reaction?

Question

Many people who lived through the plague reported that it created a sense of hopeless despair. Do the quotations from medical treatises and the objects depicted here support this idea? Why or why not?