Introduction

The Origins of Modern Western Society

The notion of “the West” has ancient origins. Greek civilization grew up in the shadow of earlier civilizations to the south and east of Greece, especially Egypt and Mesopotamia. Greeks defined themselves in relation to these more advanced cultures, which they lumped together as “the East.” They passed this conceptualization on to the Romans, who in turn transmitted it to the peoples of western and northern Europe. When Europeans established overseas colonies in the late fifteenth century, they believed they were taking Western culture with them, even though many of its elements, such as Christianity, had originated in what Europeans by that point regarded as the East. Throughout history, the meaning of “the West” has shifted, but in every era it has meant more than a geographical location.

The Ancient World

The ancient world provided several cultural elements that the modern world has inherited. First came the traditions of the Hebrews, especially their religion, Judaism, with its belief in one god and in themselves as a chosen people. The Hebrews developed their religious ideas in books that were later brought together in the Hebrew Bible, which Christians term the Old Testament. Second, Greek architectural, philosophical, and scientific ideas have exercised a profound influence on Western thought. Third, Rome provided the Latin language, the instrument of verbal and written communication for more than a thousand years, and concepts of law and government that molded Western ideas of political organization. Finally, Christianity, the spiritual faith and ecclesiastical organization that derived from the life and teachings of a Jewish man, Jesus of Nazareth, also came to condition Western religious, social, and moral values and systems.

The Hebrews

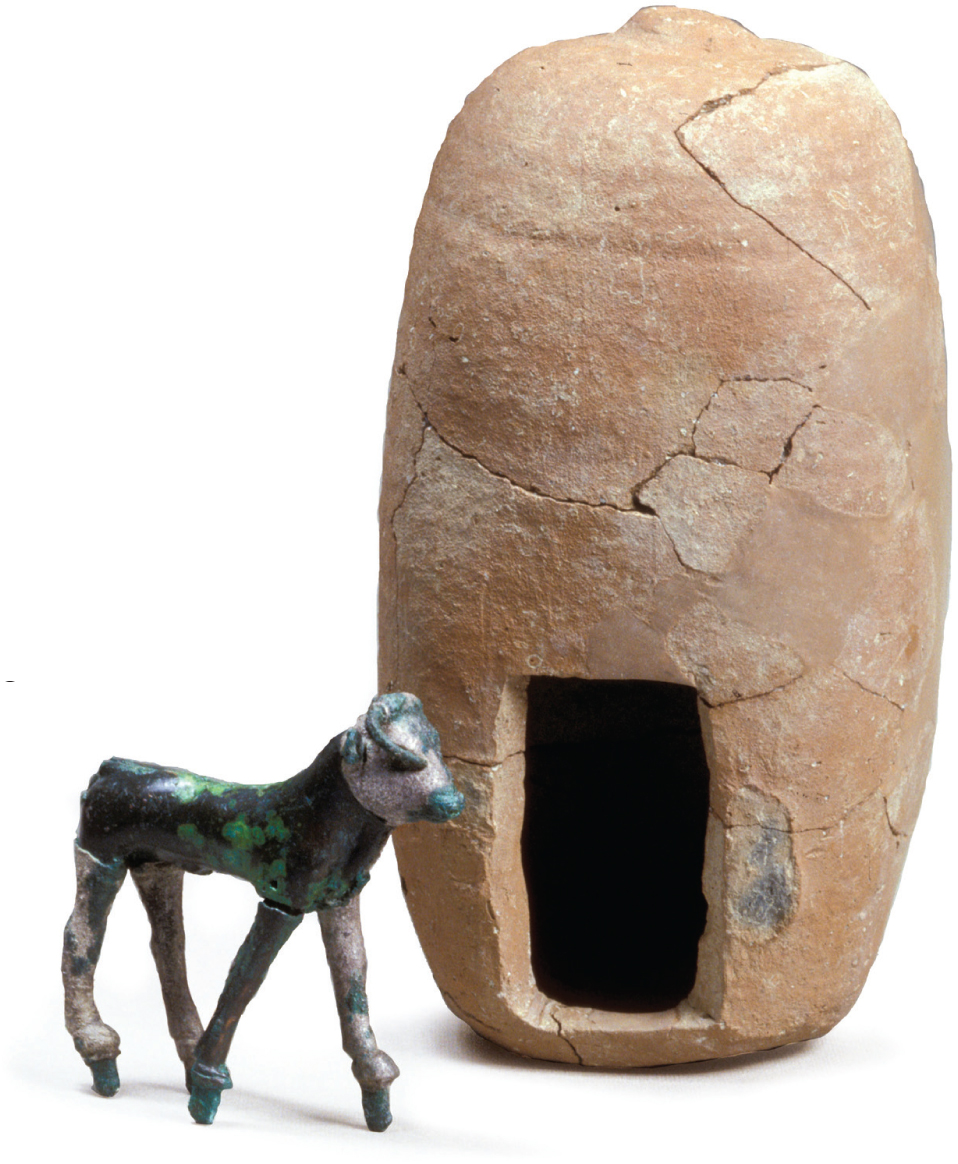

The Hebrews were nomadic pastoralists who may have migrated into the Nile Delta from the east, seeking good land for their herds of sheep and goats. According to the Hebrew Bible, they were enslaved by the Egyptians but were led out of Egypt by a charismatic leader named Moses. The Hebrews settled in the area between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River known as Canaan. They were organized into tribes, each tribe consisting of numerous families who thought of themselves as all related to one another and having a common ancestor.

In Canaan, the nomadic Hebrews encountered a variety of other peoples, whom they both learned from and fought. The Bible reports that the inspired leader Saul established a monarchy over the twelve Hebrew tribes and that the kingdom grew under the leadership of King David. David’s successor, Solomon (r. ca. 965–925 B.C.E.), launched a building program including cities, palaces, fortresses, roads, and a temple at Jerusalem, which became the symbol of Hebrew unity. This unity did not last long, however, as at Solomon’s death his kingdom broke into two separate states, Israel and Judah.

In their migration, the Hebrews had come in contact with many peoples, such as the Mesopotamians and the Egyptians, who had many gods. The Hebrews came to believe in a single god, Yahweh, who had created all things and who took a strong personal interest in the individual. According to the Bible, Yahweh made a covenant with the Hebrews: if they worshipped Yahweh as their only god, he would consider them his chosen people and protect them from their enemies. This covenant was to prove a constant force in the Hebrews’ religion, Judaism, a word taken from the kingdom of Judah.

Worship was embodied in a series of rules of behavior, the Ten Commandments, which Yahweh gave to Moses. These required certain kinds of religious observances and forbade the Hebrews to steal, lie, murder, or commit adultery, thus creating a system of ethical absolutes. From the Ten Commandments a complex system of rules of conduct was created and later written down as Hebrew law, beginning with the Torah — the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. Hebrew Scripture, a group of books written over many centuries, also contained history, hymns of praise, prophecy, traditions, advice, and other sorts of writings. Jews today revere these texts, as do many Christians, and Muslims respect them, all of which gives them particular importance.

The Greeks

The people of ancient Greece built on the traditions and ideas of earlier societies to develop a culture that fundamentally shaped Western civilization. Drawing on their day-to-day experiences as well as logic and empirical observation, the Greeks developed ways of understanding and explaining the world around them, which grew into modern philosophy and science. They also created new political forms, including the small independent city-state known as the polis. Scholars label the period dating from around 1100 B.C.E. to 323 B.C.E., in which the polis predominated, the Hellenic period. Two poleis were especially powerful: Sparta, which created a military state in which men remained in the army most of their lives, and Athens, which created a democracy in which male citizens had a direct voice.

Athens created a brilliant culture, with magnificent art and architecture whose grace and beauty still speak to people. In their comedies and tragedies, Athenians Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides were the first playwrights to treat eternal problems of the human condition. Athens also experimented with the political system we call democracy. Greek democracy meant the rule of citizens, not “the people” as a whole, and citizenship was generally limited to free adult men whose parents were citizens. Women were citizens for religious and reproductive purposes, but their citizenship did not give them the right to participate in government. Slaves, resident foreigners, and free men who were not children of a citizen were not citizens and had no political voice. Thus ancient Greek democracy did not reflect the modern concept that all people are created equal, but it did permit male citizens to share in determining the diplomatic and military policies of the polis.

Classical Greece of the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E. also witnessed an incredible flowering of philosophical ideas. Some Greeks began to question their old beliefs and myths, and sought rational rather than supernatural explanations for natural phenomena. They began an intellectual revolution with the idea that nature was predictable, creating what we now call philosophy and science. These ideas also emerged in medicine: Hippocrates, the most prominent physician and teacher of medicine of his time, sought natural explanations for diseases and natural means to treat them.

The Sophists, a group of thinkers in fifth-century-B.C.E. Athens, applied philosophical speculation to politics and language, questioning the beliefs and laws of the polis to understand their origin. They believed that excellence in both politics and language could be taught, and they provided lessons for the young men of Athens who wished to learn how to persuade others in the often-tumultuous Athenian democracy.

Socrates (ca. 470–399 B.C.E.), whose ideas are known only through the works of others, also applied philosophy to politics and to people. Because he posed questions rather than giving answers, it is difficult to say exactly what Socrates thought about many things, although he does seem to have felt that through knowledge people could approach the supreme good and thus find happiness. Most of what we know about Socrates comes from his student Plato (427–347 B.C.E.), who wrote dialogues in which Socrates asks questions and who also founded the Academy, a school dedicated to philosophy. Plato developed the theory that there are two worlds: the impermanent, changing world that we know through our senses, and the eternal, unchanging realm of “forms” that constitute the essence of true reality. According to Plato, true knowledge and the possibility of living a virtuous life come from contemplating ideal forms. Plato’s student Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.) also thought that true knowledge was possible, but he believed that such knowledge came from observation of the world, analysis of natural phenomena, and logical reasoning, not contemplation. He investigated the nature of government, ideas of matter and motion, outer space, ethics, and language and literature, among other subjects. Aristotle’s ideas later profoundly shaped both Muslim and Western philosophy and theology.

Echoing the broader culture, Plato and Aristotle viewed philosophy as an exchange between men in which women had no part. The ideal for Athenian citizen women was a secluded life, although how far this ideal was actually a reality is impossible to know. Women in citizen families probably spent most of their time at home, leaving the house only to attend religious festivals and perhaps occasionally plays.

Greek political and intellectual advances took place against a background of constant warfare. The long and bitter struggle between the cities of Athens and Sparta called the Peloponnesian War (431–404 B.C.E.) ended in Athens’s defeat. Shortly afterward, Sparta, Athens, and Thebes contested for hegemony in Greece, but no single state was strong enough to dominate the others. Taking advantage of the situation, Philip II (r. 359–336 B.C.E.) of Macedonia, a small kingdom encompassing part of modern Greece and other parts of the Balkans, defeated a combined Theban-Athenian army in 338 B.C.E. Unable to resolve their domestic quarrels, the Greeks lost their freedom to the Macedonian invader.

Philip was assassinated just two years after he had conquered Greece, and his throne was inherited by his son, Alexander. In twelve years, Alexander conquered an empire stretching from Macedonia across the Middle East into Asia as far as India. He established cities and military colonies in strategic spots as he advanced eastward, but he died at the age of thirty-two while planning his next campaign.

Alexander left behind an empire that quickly broke into smaller kingdoms, but more important, his death ushered in an era, the Hellenistic, in which Greek culture, the Greek language, and Greek thought spread widely, blending with local traditions. The Hellenistic period stretches from Alexander’s death in 323 B.C.E. to the Roman conquest in 30 B.C.E. of the kingdom established in Egypt by Alexander’s successors. Greek immigrants moved to the cities and colonies established by Alexander and his successors, spreading the Greek language, ideas, and traditions in a process scholars later called Hellenization. Local people who wanted to rise in wealth or status learned Greek. The economic and cultural connections of the Hellenistic world later proved valuable to the Romans, allowing them to trade products and ideas more easily over a broad area.

The mixing of peoples in the Hellenistic era influenced religion, philosophy, and science. The Hellenistic kings built temples to the old Greek gods and promoted rituals and ceremonies that honored them, but new deities, such as Tyche — the goddess and personification of luck, fate, chance, and fortune — also gained prominence. More people turned to mystery religions, which blended Greek and non-Greek elements and offered their adherents secret knowledge, unification with a deity, and sometimes life after death. Others turned to practical philosophies that provided advice on how to live a good life. These included Epicureanism, which advocated moderation to achieve a life of contentment, and Stoicism, which advocated living in accordance with nature. In the scholarly realm, Hellenistic thinkers made advances in mathematics, astronomy, and mechanical design. Additionally, physicians used observation and dissection to better understand the way the human body works.

Despite the new ideas, the Hellenistic period did not see widespread improvements in the way most people lived and worked. Cities flourished, but many people who lived in rural areas were actually worse off than they had been before, because of higher levels of rents and taxes. Technology was applied to military needs, but not to the production of food or other goods.

The Greek world was largely conquered by the Romans, and the various Hellenistic monarchies became part of the Roman Empire. In cultural terms the lines of conquest were reversed, however, as the Romans were tremendously influenced by Greek art, philosophy, and ideas, all of which have had a lasting impact on the modern world as well.

Rome: From Republic to Empire

The city of Rome, situated near the center of the boot-shaped peninsula of Italy, conquered all of Italy, then the western Mediterranean basin, and then areas in the east that had been part of Alexander’s empire, creating an empire that at its largest stretched from England to Egypt and from Portugal to Persia. The Romans spread the Latin language throughout much of their empire, providing a common language for verbal and written communication for more than a thousand years. They also established concepts of law and government that molded Western legal systems, ideas of political organization, and administrative practices.

The city of Rome developed from small villages and was influenced by the Etruscans who lived to the north. Sometime in the sixth century B.C.E. a group of aristocrats revolted against the ruling king and established a republican form of government in which the main institution of power was the Senate, an assembly of aristocrats, rather than a single monarch. According to tradition, this happened in 509 B.C.E., so scholars customarily divide Roman history into two primary stages: the republic, from 509 to 27 B.C.E., in which Rome was ruled by the Senate; and the empire, from 27 B.C.E. to 476 C.E., in which Roman territories were ruled by an emperor.

In the years following the establishment of the republic, the Romans fought numerous wars with their neighbors on the Italian peninsula. Their superior military institutions, organization, and manpower allowed them to conquer or take into their influence most of Italy by about 265 B.C.E. Once they had conquered an area, the Romans built roads and often shared Roman citizenship. Roman expansion continued. In a series of wars they conquered lands all around the Mediterranean, creating an overseas empire that brought them unheard-of power and wealth. First they defeated the Carthaginians in the Punic Wars, and then they turned east. Declaring the Mediterranean mare nostrum, “our sea,” the Romans began to create a political and administrative machinery to hold the Mediterranean together under a mutually shared cultural and political system of provinces ruled by governors sent from Rome.

The Romans created several assemblies through which men elected high officials and passed ordinances. The most important of these was the Senate, a political assembly — initially only of hereditary aristocrats called patricians — that advised officials and handled government finances. The common people of Rome, known as plebeians, were initially excluded from holding offices or sitting in the Senate, but a long political and social struggle led to a broadening of the base of political power to include male plebeians. The basis of Roman society for both patricians and plebeians was the family, headed by the paterfamilias, who held authority over his wife, children, and servants. Households often included slaves, who also provided labor for fields and mines.

A lasting achievement of the Romans was their development of law. Roman civil law consisted of statutes, customs, and forms of procedure that regulated the lives of citizens. As the Romans came into more frequent contact with foreigners, Roman officials applied a broader “law of the peoples,” to such matters as peace treaties, the treatment of prisoners of war, and the exchange of diplomats. All sides were to be treated the same regardless of their nationality. By the late republic, Roman jurists had widened this still further into the concept of natural law based in part on Stoic ideas they had learned from Greek thinkers. Natural law, according to these thinkers, is made up of rules that govern human behavior that come from applying reason rather than customs or traditions, and so apply to all societies. In reality, Roman officials generally interpreted the law to the advantage of Rome, of course, at least to the extent that the strength of Roman armies allowed them to enforce it. But Roman law came to be seen as one of the most important contributions Rome made to the development of Western civilization.

Law was not the only facet of Hellenistic Greek culture to influence the Romans. The Roman conquest of the Hellenistic East led to the wholesale confiscation of Greek sculpture and paintings to adorn Roman temples and homes. Greek literary and historical classics were translated into Latin; Greek philosophy was studied in the Roman schools; educated people learned Greek as well as Latin as a matter of course. Public baths based on the Greek model — with exercise rooms, swimming pools, and reading rooms — served not only as centers for recreation and exercise but also as centers of Roman public life.

The wars of conquest eventually created serious political problems for the Romans, which surfaced toward the end of the second century B.C.E. Overseas warfare required huge armies for long periods of time. A few army officers gained fabulous wealth, but most soldiers did not and returned home to find their farms in ruins. Those with cash to invest bought up small farms, creating vast estates called latifundia. Landless veterans migrated to Rome seeking work. Unable to compete with the tens of thousands of slaves in Rome, they formed a huge unemployed urban population. Rome divided into political factions, each of which named a supreme military commander, who led Roman troops against external enemies but also against each other. Civil war erupted.

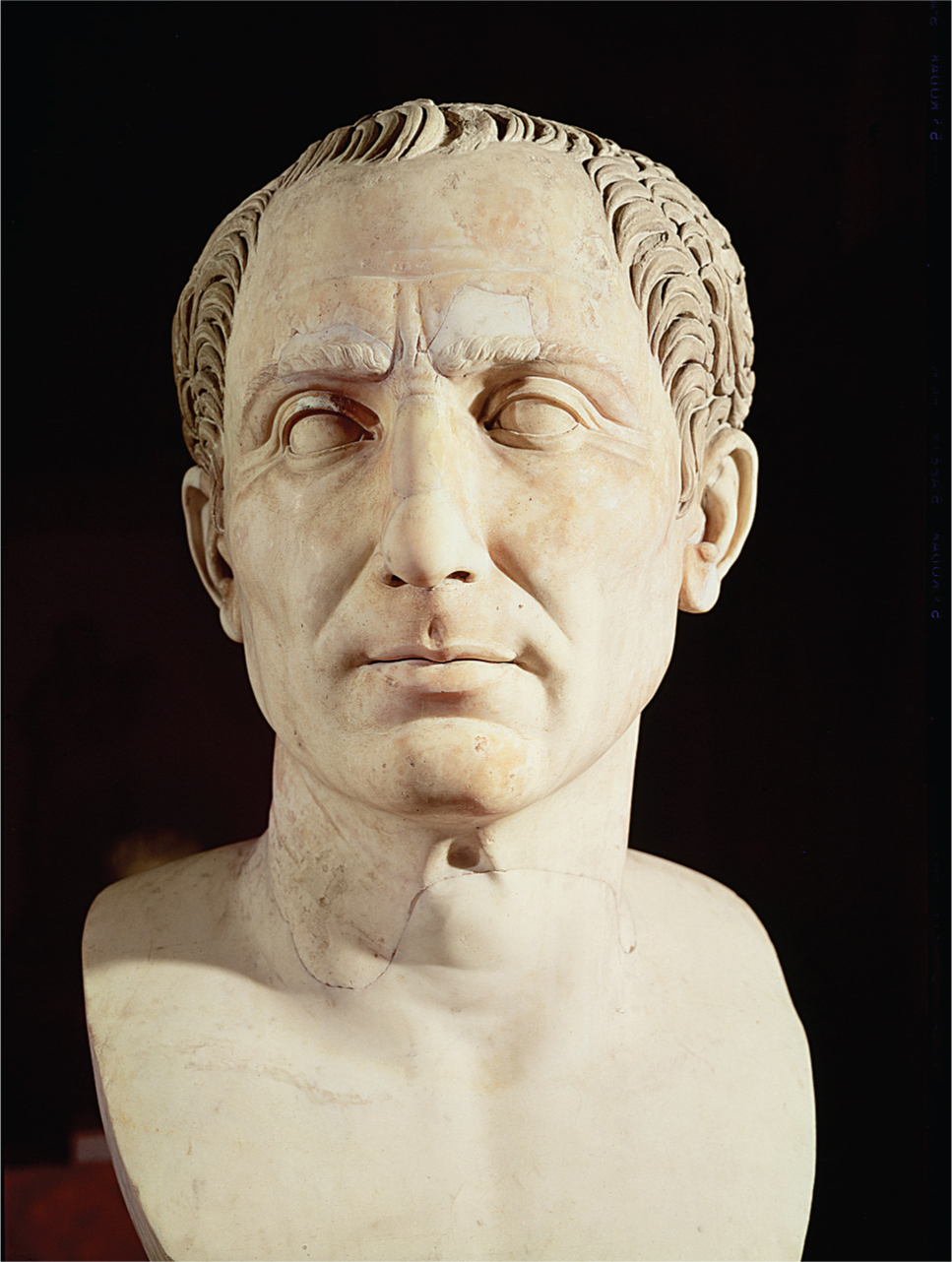

Out of the violence and disorder emerged Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.E.), a victorious general, shrewd politician, and highly popular figure. He took practical steps to end the civil war, such as expanding citizenship and sending large numbers of the urban poor to found colonies and spread Roman culture in Gaul, Spain, and North Africa. Fearful that Caesar’s popularity and ambition would turn Rome into a monarchy, a group of aristocratic conspirators assassinated him in 44 B.C.E. Civil war was renewed. In 31 B.C.E. Caesar’s grandnephew and adopted son Octavian defeated his rivals and became master of Rome. For his success, the Senate in 27 B.C.E. gave Octavian the name Augustus, meaning “revered one.” Although the Senate did not mean this to be a decisive break, that date is generally used to mark the end of the Roman Republic and the start of the Roman Empire.

Augustus rebuilt effective government. Although he claimed that he was restoring the republic, he actually transformed the government into one in which all power was held by a single ruler, gradually taking over many of the offices that traditionally had been held by separate people. Without specifically saying so, Augustus created the office of emperor. The English word emperor is derived from the Latin word imperator, an origin that reflects the fact that Augustus’s command of the army was the main source of his power.

Augustus ended domestic turmoil and secured the provinces. He founded new colonies, mainly in the western Mediterranean basin, which promoted the spread of Greco-Roman culture and the Latin language to the West. Magistrates exercised authority in their regions as representatives of Rome. Augustus broke some of the barriers between Italy and the provinces by extending citizenship to many of the provincials who had supported him. Later emperors added more territory, and a system of Roman roads and sea-lanes united the empire, with trade connections extending to India and China. For two hundred years the Mediterranean world experienced what later historians called the pax Romana — a period of prosperity, order, and relative peace.

In the third century C.E. this prosperity and stability gave way to a period of domestic upheaval and foreign invasion. Rival generals backed by their troops contested the imperial throne in civil wars. Groups the Romans labeled “barbarians,” such as the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Gauls, and others, migrated into and invaded the Roman Empire from the north and east. Civil war and invasions devastated towns and farms, causing severe economic depression. The emperors Diocletian (r. 284–305 C.E.) and Constantine (r. 306–337 C.E.) tried to halt the general disintegration by reorganizing the empire, expanding the state bureaucracy, building more defensive works, and imposing heavier taxes. For administrative purposes, Diocletian divided the empire into a western half and an eastern half, and Constantine established the new capital city of Constantinople in the East. Their attempts to solve the empire’s problems failed, however. The emperors ruling from Constantinople could not provide enough military assistance to repel invaders in the western half of the Roman Empire. In 476 a Germanic chieftain, Odoacer, deposed the Roman emperor in the West and did not take on the title of emperor, calling himself instead the king of Italy. This date thus marks the official end of the Roman Empire in the West, although the Roman Empire in the East, later called the Byzantine Empire, would last for nearly another thousand years.

After the Western Roman Empire’s decline, the rich legacy of Greco-Roman culture was absorbed by the medieval world. The Latin language remained the basic medium of communication among educated people in central and western Europe for the next thousand years; for almost two thousand years, Latin literature formed the core of all Western education. Roman roads, buildings, and aqueducts remained in use. Rome left its mark on the legal and political systems of most European countries. Rome had preserved the best of ancient culture for later times.

The Spread of Christianity

The ancient world also left behind a powerful religious legacy, Christianity. Christianity derives from the teachings of a Jewish man, Jesus of Nazareth (ca. 3 B.C.E.–29 C.E.). According to the accounts of his life written down and preserved by his followers, Jesus preached of a heavenly kingdom of eternal happiness in a life after death and of the importance of devotion to God and love of others. His teachings were based on Hebrew Scripture and reflected a conception of God and morality that came from Jewish tradition, but he deviated from traditional Jewish teachings in insisting that he taught in his own name, not simply in the name of Yahweh. He came to establish a spiritual kingdom, he said, not an earthly one, and he urged his followers and listeners to concentrate on the world to come, not on material goods or earthly relationships. Some Jews believed that Jesus was the long-awaited savior who would bring prosperity and happiness, while others thought he was religiously dangerous. The Roman official of Judaea, Pontius Pilate, feared that the popular agitation surrounding Jesus could lead to revolt against Rome. He arrested Jesus, met with him, and sentenced him to death by crucifixion — the usual method for common criminals. Jesus’s followers maintained that he rose from the dead three days later.

Those followers might have remained a small Jewish sect but for the preaching of a Hellenized Jew, Paul of Tarsus (ca. 5–67 C.E.). Paul traveled widely and wrote letters of advice, many of which were copied and circulated, transforming Jesus’s ideas into more specific moral teachings. Paul urged that Jews and non-Jews be accepted on an equal basis, and the earliest converts included men and women from all social classes. People were attracted to Christian teachings for a variety of reasons: it offered a message of divine forgiveness and eternal life, taught that every individual has a role to play in building the kingdom of God, and fostered a deep sense of community and identity in the often highly mobile Roman world.

Some Roman officials and emperors opposed Christianity and attempted to stamp it out, but most did not, and by the second century Christianity began to establish more permanent institutions, including a hierarchy of officials. It attracted more highly educated individuals, and modified teachings that seemed upsetting to Romans. In 313 the emperor Constantine legalized Christianity, and in 380 the emperor Theodosius made it the official religion of the empire. Carried by settlers, missionaries, and merchants to Gaul, Spain, North Africa, and Britain, Christianity formed a basic element of Western civilization.

Christian writers also played a powerful role in the conservation of Greco-Roman thought. They used Latin as their medium of communication, thereby preserving it. They copied and transmitted classical texts. Writers such as Saint Augustine of Hippo (354–430) used Roman rhetoric and Roman history to defend Christian theology. In so doing, they assimilated classical culture into Christian teaching.

The Middle Ages

Fifteenth-century scholars believed that they were living in a period of rebirth that had recaptured the spirit of ancient Greece and Rome. What separated their time from classical antiquity, in their opinion, was a long period of darkness to which a seventeenth-century professor gave the name “Middle Ages.” In this conceptualization, Western history was divided into three periods — ancient, medieval, and modern — an organization that is still in use today. Recent scholars have demonstrated, however, that the thousand-year period between roughly the fifth and fourteenth centuries was not one of stagnation, but one of great changes in every realm of life: social, political, intellectual, economic, and religious. The men and women of the Middle Ages built on the cultural heritage of the Greco-Roman world and on the traditions of barbarian groups to create new ways of doing things.

The Early Middle Ages

The time period that historians mark off as the early Middle Ages, extending from about the fifth to the tenth centuries, saw the emergence of a distinctly Western society and culture. The geographical center of that society shifted northward from the Mediterranean basin to western Europe. Whereas a rich urban life and flourishing trade had characterized the ancient world, the barbarian invasions led to the decline of cities and the destruction of commerce. Early medieval society was rural and local, with the village serving as the characteristic social unit.

Several processes were responsible for the development of European culture. First, Europe became Christian. Missionaries traveled throughout Europe instructing Germanic, Celtic, and Slavic peoples in the basic tenets of the Christian faith. Seeking to gain more converts, the Christian Church incorporated pagan beliefs and holidays, creating new rituals and practices that were meaningful to people, and creating a sense of community through parish churches and the veneration of saints.

Second, as barbarian groups migrated into the Western Roman Empire, they often intermarried with the old Roman aristocracy. The elite class that emerged held the dominant political, social, and economic power in early — and later — medieval Europe. Barbarian customs and tradition, such as ideals of military prowess and bravery in battle, became part of the mental furniture of Europeans.

Third, in the seventh and eighth centuries, Muslim military conquests carried Islam, the religion inspired by the prophet Muhammad (ca. 571–632), from the Arab lands across North Africa, the Mediterranean basin, and Spain into southern France. The Arabs eventually translated many Greek texts. When, beginning in the ninth century, those texts were translated from Arabic into Latin, they came to play a role in the formation of European scientific and philosophical thought.

Monasticism, an ascetic form of Christian life first practiced in Egypt and characterized by isolation from the broader society, simplicity of living, and abstention from sexual activity, flourished and expanded in both the Byzantine East and the Latin West. Medieval people believed that the communities of monks and nuns provided an important service: prayer on behalf of the broader society. In a world lacking career opportunities, monasteries also offered education for the children of the upper classes. Men trained in monastery schools served royal and baronial governments as advisers, secretaries, diplomats, and treasurers; monks in the West also pioneered the clearing of wasteland and forestland.

One of the barbarian groups that settled within the Roman Empire and allied with the Romans was the Franks, and after the Roman Empire collapsed they expanded their holdings, basing some of their government on Roman principles. In the eighth century the dynamic warrior-king of the Franks, Charles the Great, or Charlemagne (r. 768–814), came to control most of central and western continental Europe except Muslim Spain, and western Europe achieved a degree of political unity. Charlemagne supported Christian missionary efforts and encouraged both classical and Christian scholarship. His coronation in 800 by the pope at Rome in a ceremony filled with Latin anthems represented a fusion of classical, Christian, and barbarian elements, as did Carolingian culture more generally. In the ninth century Vikings, Muslims, and Magyars (early Hungarians) raided and migrated into Europe, leading to the collapse of centralized power. Charlemagne’s empire was divided, and real authority passed into the hands of local strongmen. Out of this vulnerable society, which was constantly threatened by outside invasions, a new political form involving mutual obligations, later called “feudalism,” developed. The power of the local nobles in the feudal structure rested on landed estates worked by peasants in another system of mutual obligation termed “manorialism,” in which the majority of peasants were serfs, required to stay on the land where they were born and pay obligations to a lord in labor and products.

The High and Later Middle Ages

By the beginning of the eleventh century, the European world showed distinct signs of recovery, vitality, and creativity. Over the next three centuries, a period called the High Middle Ages, that recovery and creativity manifested itself in every facet of culture — economic, social, political, intellectual, and artistic. A greater degree of peace paved the way for these achievements.

The Viking, Muslim, and Magyar invasions gradually ended. Warring knights supported ecclesiastical pressure against violence, and disorder declined. A warming climate, along with technological improvements such as water mills and horse-drawn plows, increased the available food supply. Most people remained serfs, living in simple houses in small villages, but a slow increase in population led to new areas being cultivated, and some serfs were able to buy their freedom.

Relative security and the increasing food supply allowed for the growth and development of towns in the High Middle Ages. Towns gained legal and political rights, merchant and craft guilds grew more powerful, and towns became centers of production as well as trading centers. In medieval social thinking, three classes existed: the clergy, who prayed; the nobility, who fought; and the peasantry, who tilled the land. The merchant class, engaging in manufacturing and trade, seeking freedom from the jurisdiction of feudal lords, and pursuing wealth with a fiercely competitive spirit, fit none of the standard categories. Townspeople represented a radical force for change. Trade brought in new ideas as well as merchandise, and towns developed into intellectual and cultural centers.

The growth of towns and cities went hand in hand with a revival of regional and international trade. For example, Italian merchants traveled to the regional fairs of France and Flanders to exchange silk from China and slaves from the Crimea for English woolens, French wines, and Flemish textiles. Merchants adopted new business techniques and a new attitude toward making money. They were eager to invest surplus capital to make more money. These developments added up to what scholars have termed a commercial revolution, a major turning point in the economic and social life of the West. The development of towns and commerce was to lay the foundations for Europe’s transformation, centuries later, from a rural agricultural society into an urban industrial society — a change with global implications.

The High Middle Ages also saw the birth of the modern centralized state. The concept of the state had been one of Rome’s great legacies to Western civilization, but for almost five hundred years after the disintegration of the Roman Empire in the West, political authority was weak. Charlemagne had far less control of what went on in his kingdom than Roman emperors had, and after the Carolingian Empire broke apart, political authority was completely decentralized, with power spread among many feudal lords. Beginning in the last half of the tenth century, however, feudal rulers started to develop new institutions of law and government that enabled them to assert their power over lesser lords and the general population. Centralized states slowly crystallized, first in France and England, and then in Spain and northern Europe. In Italy and Germany, however, strong independent local authorities predominated.

Medieval rulers required more officials, larger armies, and more money with which to pay for them. They developed financial bureaucracies, of which the most effective were those in England. They also sought to transform a hodgepodge of oral and written customs and rules into a uniform system of laws acceptable and applicable to all their peoples. In France, local laws and procedures were maintained, but the king also established a royal court that published laws and heard appeals. In England, the king’s court regularized procedures, and the idea of a common law that applied to the whole country developed. Fiscal and legal measures enacted by King John led to opposition from the high nobles of England, who in 1215 forced him to sign the Magna Carta, agreeing to observe the law. English kings following John recognized this common law, a law that their judges applied throughout the country. Exercise of common law often involved juries of local people to answer questions of fact. The common law and jury systems of the Middle Ages have become integral features of Anglo-American jurisprudence. In the fourteenth century kings also summoned meetings of the leading classes in their kingdoms, and thus were born representative assemblies, most notably the English Parliament.

In their work of consolidation and centralization, kings increasingly used the knowledge of university-trained officials. Universities first emerged in western Europe in the twelfth century. Medieval universities were educational institutions for men that produced trained officials for the new bureaucratic states. The universities at Bologna in Italy and Montpellier in France, for example, were centers for the study of Roman law. Paris became the leading university for the study of philosophy and theology. Medieval Scholastics (philosophers and theologians) sought to harmonize Greek philosophy, especially the works of Aristotle, with Christian teaching. They wanted to use reason to deepen the understanding of what was believed on faith. At the University of Paris, Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) wrote an important synthesis of Christian revelation and Aristotelian philosophy in his Summa Theologica. Medieval universities developed the basic structures familiar to modern students: colleges, universities, examinations, and degrees. Colleges and universities are another major legacy of the Middle Ages to the modern world.

At the same time that states developed, energetic popes built their power within the Western Christian Church and asserted their superiority over kings and emperors. A papal call to retake the holy city of Jerusalem led to nearly two centuries of warfare between Christians and Muslims. Christian warriors, clergy, and settlers moved out from western and central Europe in all directions, so that through conquest and colonization border regions were gradually incorporated into a more uniform European culture.

Most people in medieval Europe were Christian, and the village or city church was the center of community life, where people attended services, honored the saints, and experienced the sacraments. The village priest blessed the fields before the spring planting and the fall harvesting. In everyday life people engaged in rituals heavy with religious symbolism, and every life transition was marked by a ceremony with religious elements. Guilds of merchants sought the protection of patron saints and held elaborate public celebrations on the saints’ feast days. Indeed, the veneration of saints — men and women whose lives contemporaries perceived as outstanding in holiness — and an increasingly sophisticated sacramental system became central features of popular religion. University lectures and meetings of parliaments began with prayers. Kings relied on the services of bishops and abbots in the work of the government. Gothic cathedrals, where people saw beautiful stained-glass windows and listened to complex music, manifested medieval people’s deep Christian faith and their pride in their own cities.

The high level of energy and creativity that characterized the twelfth and thirteenth centuries could not be sustained indefinitely. In the fourteenth century every conceivable disaster struck western Europe. The climate turned colder and wetter, leading to poor harvests and widespread famine. People weakened by hunger were more susceptible to disease, and in the middle of the fourteenth century the bubonic plague (or Black Death) swept across the continent, taking a terrible toll on population. England and France became deadlocked in a long and bitter struggle known as the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453). War devastated the countryside, especially in France, leading to widespread discontent and peasant revolts. Workers in cities also revolted against dismal working conditions, and violent crime and ethnic tensions increased. Many urban residents were increasingly dissatisfied with the Christian Church and turned to heretical movements that challenged church power. Schism in the Catholic Church resulted in the simultaneous claim by two popes of jurisdiction. Yet, in spite of the pessimism and crises, important institutions and cultural forms, including representative assemblies and national literatures, emerged.

Early Modern Europe

While war gripped northern Europe, a new culture emerged in southern Europe. The fourteenth century witnessed the beginning of remarkable changes in many aspects of Italian intellectual, artistic, and cultural life. Artists and writers thought they were living in a new golden age, but not until the sixteenth century was this change given the label we use today — the Renaissance, from the French version of a word meaning “rebirth.” The term was first used by the artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) to describe the art of “rare men of genius” such as his contemporary Michelangelo. Through their works, Vasari judged, the glory of the classical past had been reborn after centuries of darkness, or had perhaps even been surpassed. Vasari used the word Renaissance to describe painting, sculpture, and architecture, what he termed the “Major Arts.” Gradually, however, Renaissance was used to refer to many aspects of life at this time, first in Italy and then in the rest of Europe. This new attitude had a slow diffusion out of Italy, with the result that the Renaissance happened at different times in different parts of Europe. Italian art of the fourteenth through the early sixteenth centuries is described as “Renaissance,” as is English literature of the late sixteenth century (including Shakespeare).

About a century after Vasari coined the word Renaissance, scholars began to view the cultural and political changes of the Renaissance, along with the religious changes of the Reformation and the European voyages of exploration, as ushering in the “modern” world. Since then, some historians have chosen to view the Renaissance as a bridge between the medieval and modern eras, as it corresponded chronologically with the late medieval period and as there was much continuity along with the changes. Others have questioned whether the word Renaissance should be used at all to describe an era in which many social groups saw decline rather than advancement. These debates remind us that the labels medieval, Renaissance, and modern are intellectual constructs devised after the fact. They all contain value judgments, as do other chronological designations, such as the “golden age” of Athens and the “Roaring Twenties.”

The Renaissance

In the commercial revival of the Middle Ages, ambitious merchants amassed great wealth, especially in the city-states of northern Italy. These city-states were communes in which all citizens shared power, but political instability often led to their transformation into city-states ruled by single individuals. As their riches and power grew, rulers and merchants displayed their wealth in great public buildings as well as magnificent courts — palaces where they lived and conducted business. Political rulers, popes, and powerful families hired writers, artists, musicians, and architects through the system of patronage, which allowed for a great outpouring of culture.

The Renaissance was characterized by self-conscious awareness among fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Italians — particularly scholars and writers known as humanists — that they were living in a new era. Key to this attitude was a serious interest in the Latin classics, a belief in individual potential, and a more secular attitude toward life. All of these are evident in the political theory developed in the Renaissance, particularly that of Machiavelli. Humanists opened schools to train boys and young men for active lives of public service, but had doubts about whether humanist education was appropriate for women. As humanism spread to northern Europe, religious concerns became more pronounced, and Christian humanists set out plans for the reform of church and society. Their ideas reached a much wider audience than did those of early humanists because of the development of the printing press with movable metal type, which revolutionized communication.

Interest in the classical past and in the individual also shaped Renaissance art in terms of style and subject matter. Painting became more naturalistic, and the individual portrait emerged as a distinct artistic genre. Wealthy merchants, cultured rulers, and powerful popes all hired painters, sculptors, and architects to design and ornament public and private buildings. Art in Italy became more secular and classical, while that in northern Europe retained a more religious tone. Artists began to understand themselves as having a special creative genius, though they continued to produce works on order for patrons, who often determined the content and form.

Social hierarchies in the Renaissance built on those of the Middle Ages, with the addition of new features that evolved into the modern social hierarchies of race, class, and gender. In the fifteenth century black slaves entered Europe in sizable numbers for the first time since the collapse of the Roman Empire, and Europeans fit them into changing understandings of ethnicity and race. The medieval hierarchy of orders based on function in society intermingled with a new hierarchy based on wealth, with new types of elites becoming more powerful. The Renaissance debate about women led many to discuss women’s nature and proper role in society, a discussion sharpened by the presence of a number of ruling queens in this era.

Beginning in the fifteenth century rulers utilized aggressive methods to rebuild their governments. First in the regional states of Italy, then in the expanding monarchies of France, England, and Spain, rulers began the work of reducing violence, curbing unruly nobles, and establishing domestic order. They attempted to secure their borders and enhanced methods of raising revenue. The monarchs of western Europe emphasized royal majesty and royal sovereignty and insisted on the respect and loyalty of all subjects, including the nobility. In central Europe the Holy Roman emperors attempted to do the same, but they were not able to overcome the power of local interests to create a unified state.

The Reformation

Calls for reform of the Christian Church began very early in its history. When Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth century, many believers thought that the church had abandoned its original mission, and they called for a return to a church that was not linked to the state. Throughout the Middle Ages, individuals and groups argued that the church had become too wealthy and powerful, and urged monasteries, convents, bishoprics, and the papacy to give up their property and focus on service to the poor. Some asserted that basic teachings of the church were not truly Christian and that changes were needed in theology as well as in institutional structures and practices. The Christian humanists of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries urged reform, primarily through educational and social change. Throughout the centuries, men and women believed that the early Christian Church represented a golden age akin to the golden age of the classical past celebrated by Renaissance humanists.

Thus sixteenth-century cries for reformation were hardly new. What was new, however, was the breadth with which they were accepted and their ultimate impact. In 1500 there was one Christian Church in western Europe to which all Christians at least nominally belonged. Fifty years later there were many, a situation that continues today. Thus, along with the Renaissance, the Reformation is often seen as a key element in the creation of the “modern” world.

In 1517 Martin Luther (1483–1546), a priest and professor of theology at a small German university, launched an attack on clerical abuses. The Catholic Church in the early sixteenth century had serious problems, and many individuals and groups had long called for reform. This background of discontent helps explain why Martin Luther’s ideas found such a ready audience. Luther and other Protestants developed a new understanding of Christian doctrine that emphasized faith, the power of God’s grace, and the centrality of the Bible. Protestant ideas were attractive to educated people and urban residents, and they spread rapidly through preaching, hymns, and the printing press. By 1530 many parts of the Holy Roman Empire and Scandinavia had broken with the Catholic Church.

Some reformers developed more radical ideas about infant baptism, ownership of property, and the separation between church and state. Both Protestants and Catholics regarded these as dangerous, and radicals were banished or executed. The German Peasants’ War, in which Luther’s ideas were linked to calls for social and economic reform, was similarly put down harshly. The Protestant reformers did not break with medieval ideas about the proper gender hierarchy, though they did elevate the status of marriage and viewed orderly households as the key building blocks of society.

The progress of the Reformation was shaped by the political situation in the Holy Roman Empire. The Habsburg emperor, Charles V, ruled almost half of Europe along with Spain’s overseas colonies. Within the empire his authority was limited, however, and local princes, nobles, and cities actually held the most power. This decentralization allowed the Reformation to spread. Charles remained firmly Catholic, and in the 1530s religious wars began in Germany. These were brought to an end with the Peace of Augsburg in 1555, which allowed rulers to choose whether their territory would be Catholic or Lutheran.

In England, the political issue of the royal succession triggered that country’s break with Rome, and a Protestant Church was established. Protestant ideas also spread into France and eastern Europe. In all these areas, a second generation of reformers built on Lutheran and Zwinglian ideas to develop their own theology and plans for institutional change. The most important of the second-generation reformers was John Calvin, whose ideas would come to shape Christianity over a much wider area than did Luther’s. The Roman Catholic Church responded slowly to the Protestant challenge, but by the 1530s the papacy was leading a movement for reform within the church instead of blocking it. Catholic doctrine was reaffirmed at the Council of Trent, and reform measures, such as the opening of seminaries for priests and a ban on holding multiple church offices, were introduced. New religious orders such as the Jesuits and the Ursulines spread Catholic ideas through teaching, and in the case of the Jesuits through missionary work.

Religious differences led to riots, civil wars, and international conflicts in the later sixteenth century. In France and the Netherlands, Calvinist Protestants and Catholics used violence against each other, and religious differences became mixed with political and economic grievances. Long civil wars resulted; one in the Netherlands became an international conflict. War ended in France with the Edict of Nantes in which Protestants were given some civil rights, and in the Netherlands with a division of the country into a Protestant north and a Catholic south. The era of religious wars was also the time of the most extensive witch persecutions in European history, as both Protestants and Catholics tried to rid their cities and states of people they regarded as linked to the Devil.

The Renaissance and the Reformation are often seen as two of the key elements in the creation of the “modern” world. The radical changes brought by the Reformation contained many aspects of continuity, however. Sixteenth-century reformers looked back to the early Christian Church for their inspiration, and many of their reforming ideas had been advocated for centuries. Most Protestant reformers worked with political leaders to make religious changes, just as early church officials had worked with Emperor Constantine and his successors as Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth century. The spread of Christianity and the spread of Protestantism were accomplished not only by preaching, persuasion, and teaching, but also by force and violence. The Catholic Reformation was carried out by activist popes, a church council, and new religious orders, as earlier reforms of the church had been.

Just as they linked with earlier developments, the events of the Reformation were also closely connected with what is often seen as the third element in the “modern” world, discussed in the first chapter of this book: European Exploration and Conquest. Only a week after Martin Luther stood in front of Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms declaring his independence in matters of religion, Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese sea captain with Spanish ships, was killed in a group of islands off the coast of Southeast Asia. Charles V had provided the backing for Magellan’s voyage, the first to circumnavigate the globe. Magellan viewed the spread of Christianity as one of the purposes of his trip, and later in the sixteenth century institutions created as part of the Catholic Reformation, including the Jesuit order and the Inquisition, would operate in European colonies overseas as well as in Europe itself. The islands where Magellan was killed were later named the Philippines, in honor of Charles’s son Philip, who sent an ill-fated expedition, the Spanish Armada, against Protestant England. Philip’s opponent Queen Elizabeth was similarly honored when English explorers named a huge chunk of territory in North America “Virginia” as a tribute to their “Virgin Queen.” The desire for wealth and power was an important motivation in the European voyages and colonial ventures, but so was religious zeal.