A History of Western Society: Printed Page 658

LIVING IN THE PAST

The Steam Age

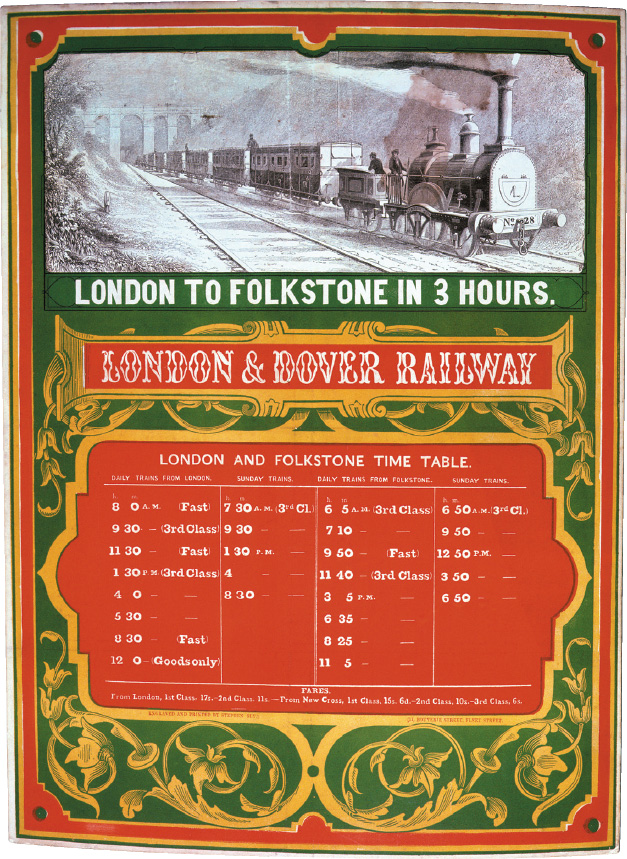

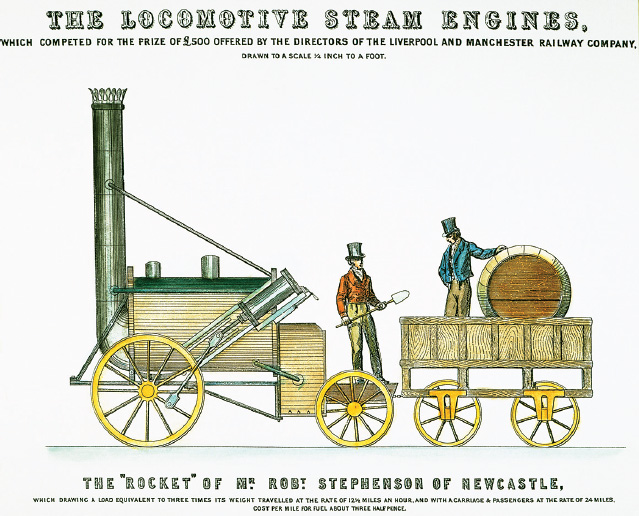

On Tuesday, October 6, 1829, a huge crowd gathered at the small town of Rainhill in northern England. Pedestrians and horse-drawn carriages jostled for space as a band played and the Union Jack waved. The occasion was a race over a newly laid two-mile stretch of track sponsored by the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company. The victor was the Rocket, a locomotive designed by George Stephenson, the company’s chief engineer, a man of modest origins who had no formal schooling. Pulling heavy wagons, Rocket first achieved over 13 miles per hour and then astounded the crowds by whizzing by at 24 miles per hour when the wagons were detached. It was probably the fastest a vehicle had traveled in history.*

The last and culminating invention of the Industrial Revolution, the railroad dramatically revealed the power and increased the speed of the new age. Until the coming of the railroad, travel was largely measured by the distance that a human or a horse could cover before becoming exhausted. Steam power created a revolution in human transportation, allowing a constant, rapid rate of travel with no limits on its duration. Time and space suddenly and drastically contracted, as faraway places could be reached in one-third the time or less. As the poet Heinrich Heine proclaimed in 1843, “What changes must now occur, in our way of looking at things, in our notions! … I feel as if the mountains and forests of all countries were advancing on Paris. Even now, I can smell the German linden trees; the North Sea’s breakers are rolling against my door.”†

Racing down the track at speeds that reached 50 miles per hour by 1850 was an overwhelming experience. Some great painters, notably Joseph M. W. Turner (1775-1851) and Claude Monet (1840-1926), succeeded in expressing this sense of power and awe. Contemporary novelists also recorded their impressions of early train travel, as in this striking passage by Charles Dickens: “Through the hollow, on the height, by the heath, by the orchard, by the park, by the garden, over the canal, across the river, where the sheep are feeding, where the mill is going, where the barge is floating, where the dead are lying, where the factory is smoking, where the stream is running, where the village clusters … away with a strike and a roar and a rattle, and no trace to leave behind but dust and vapour.”‡ After surviving a terrible railroad crash, Dickens himself developed an intense fear of train travel. The increase in speed also led doctors to worry about the effects of the constant noise and vibration on passengers and crew.

Despite these concerns, the railroad quickly became a central institution of society. So did the massive new train stations, the cathedrals of the industrial age. Leading railway engineers such as Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Thomas Brassey, whose tunnels pierced mountains and whose bridges spanned valleys, became public idols — the astronauts of their day.

*Christopher McGowan, Rail, Steam, and Speed: The “Rocket” and the Birth of Steam Locomotion (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), p. 21.

†Quoted in Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), p. 37.

‡Charles Dickens, Dombey and Son (Ware, U.K.: Wordsworth Editions, 1999), p. 262.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

Question

Why was the train so revolutionary? What evidence is provided here for contemporaries’ perceptions of train travel?

Question

Why is the train less important in today’s culture?