A History of Western Society: Printed Page 800

LIVING IN THE PAST

The Immigrant Experience

Between 1800 and 1930, 60 million Europeans left their homelands in search of better lives. About half moved to the United States; between 1890 and 1925 over 20 million men, women, and children passed through the Ellis Island Immigration Station in New York City harbor. During these years, southern and eastern Europeans, such as Italians, Poles, and Russian Jews, far outnumbered the northern Europeans who had predominated in the mid-nineteenth-century wave of migration to the United States. Today over 40 percent of Americans are descendants of people who went through immigration control on Ellis Island. These figures give some idea of the immense number of people involved in this great migration, but statistics hardly capture what it was like to pull up stakes and move to America.

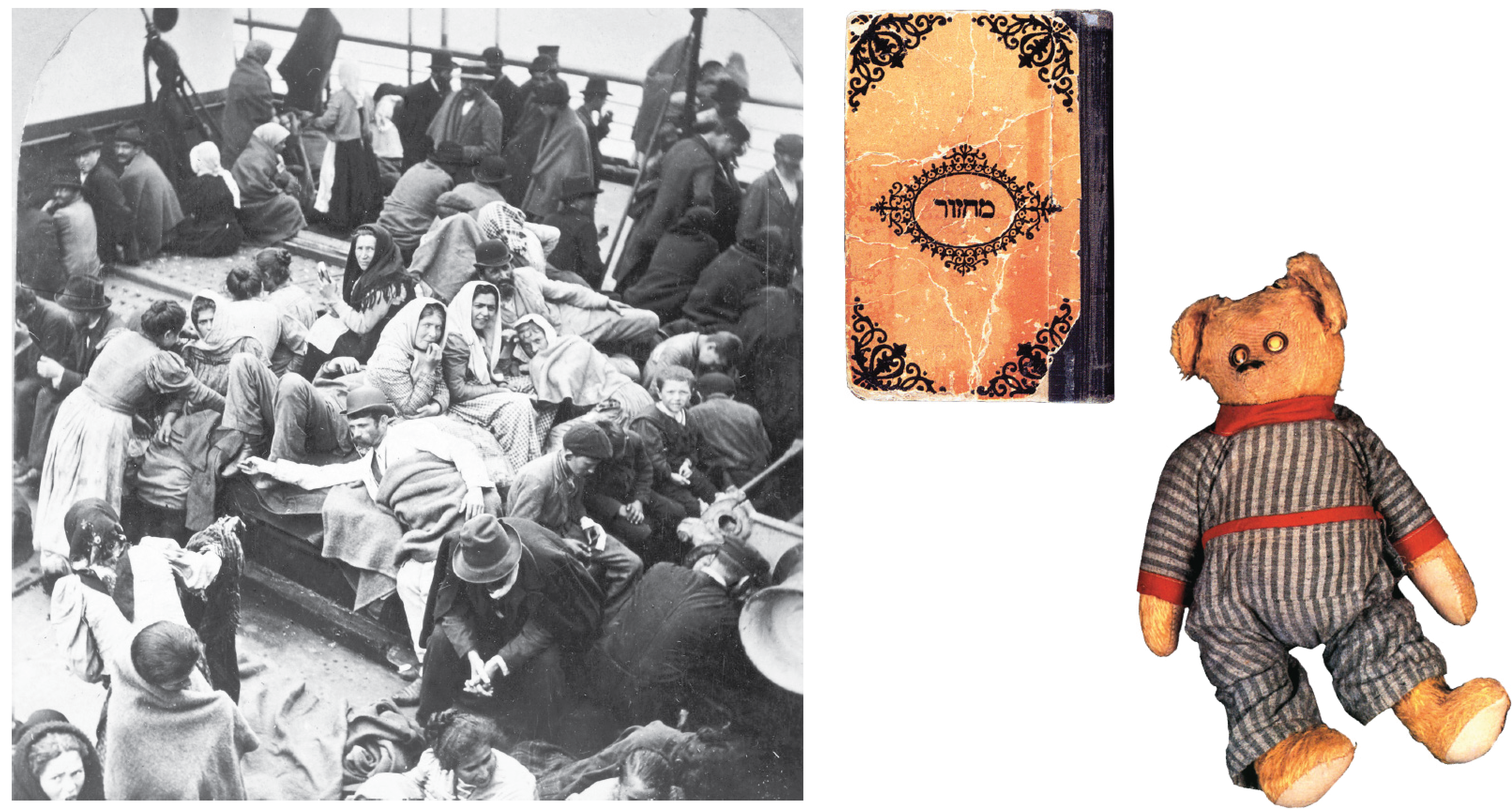

Transporting migrants across the North Atlantic was big business. Well-established steamship companies such as Cunard, White Star, and Hamburg-America advertised inexpensive fares and good accommodations. The reality was usually different. For the vast majority who could afford only third-class passage in the steerage compartment (so called because it was located near the ship’s rudder), the eight- to fourteen-day journey overseas from Naples, Hamburg, or Liverpool was cramped, cold, and unsanitary. Yet poor job prospects and religious or political persecution at home — and the lure of America’s booming economy — led many to take the journey.

Once they arrived at Ellis Island, steerage passengers were subjected to a four- to five-hour examination in the Great Hall. Physicians checked their health. Customs officers inspected legal documents. Bureaucrats administered intelligence tests and evaluated the migrants’ financial and moral status. The exams worried and sometimes insulted the new arrivals. As one Polish-Jewish immigrant remembered, “They asked us questions. ‘How much is two and one? How much is two and two?’ But the next young girl, also from our city, went and they asked her, ‘How do you wash stairs, from the top or from the bottom?’ She says, ‘I don’t come to America to wash stairs.’”

Migrants with obvious illnesses were required to stay in the island’s hospital as long as several weeks to see if they improved. Sick passengers whom officials judged either a threat to public health or a likely drain on public finances were sent home. Suspected anarchists and, later, Bolsheviks were also deported.

By today’s standards, it was remarkably easy for those seeking to establish permanent residency to enter the United States — only about 2 percent of all migrants were denied entry. After they cleared processing, the new arrivals were ferried to New York City, where they either stayed or moved to other industrialized cities of the Northeast and Midwest. The migrants typically took unskilled jobs for low wages, but by keeping labor costs down, they fueled the rapid industrialization of late-nineteenth-century America. They furthermore transformed the United States from a land of predominantly British and northern European settlers into the multiethnic melting pot of myth and fame.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

Question

Why did so many Europeans make the difficult and sometimes-dangerous transatlantic trip to the United States?

Question

What were the main concerns of U.S. immigration officials as they evaluated the new arrivals? Did U.S. officials treat immigrants fairly?