A History of Western Society: Printed Page 926

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 930

INDIVIDUALS IN SOCIETY

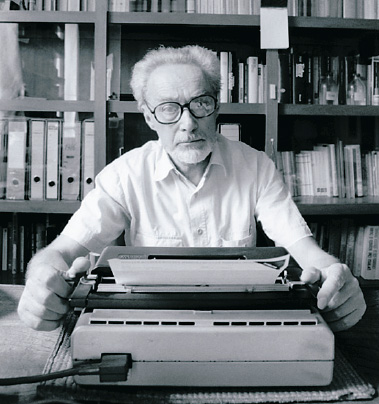

Primo Levi

Most Jews deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau were murdered soon after arriving, but the Nazis made some prisoners into slave laborers, and a few of them survived. Primo Levi (1919–1987), one of these laborers, lived to become one of the most influential witnesses to the Holocaust.

Like much of Italy’s small Jewish community, Levi’s family belonged to the urban professional classes. Levi graduated from the University of Turin with highest honors in chemistry in 1941. Growing discrimination against Italian Jews led him to join the antifascist resistance two years later. Captured, he was deported to Auschwitz with 650 Italian Jews in February 1944. Stone-faced SS men picked 96 men, Levi among them, and 29 women from this group to work in labor camps; the rest were gassed upon arrival.

Levi and his fellow prisoners were kicked, punched, stripped, branded with tattoos, crammed into huts, and worked unmercifully. Hoping for some prisoner solidarity, Levi found only a desperate struggle of each against all and enormous status differences among prisoners. Many bewildered newcomers, beaten and demoralized by their bosses — the most privileged prisoners — collapsed and died. Others struggled to secure their own privileges, however small, because food rations and working conditions were so abominable that prisoners who were not bosses usually perished in two to three months.

Sensitive and noncombative, Levi found himself sinking into oblivion. But instead of joining the mass of the “drowned,” he became one of the “saved” — a complicated surprise with moral implications that he would ponder all his life. As Levi explained in Survival in Auschwitz (1947), the usual road to salvation in the camps was some kind of collaboration with German power. Savage German criminals were released from prison to become brutal camp guards; non-Jewish political prisoners competed for jobs entitling them to better conditions; and, especially troubling for Levi, a few Jews plotted and struggled to gain the power of life and death over other Jewish prisoners.

Though not one of these Jewish bosses, Levi believed that he, like almost all survivors, had entered the “gray zone” of moral compromise. “Nobody can know for how long and under what trials his soul can resist before yielding or breaking,” Levi wrote. “The harsher the oppression, the more widespread among the oppressed is the willingness, with all its infinite nuances and motivations, to collaborate.”* The camps held no saints, he believed: the Nazi system degraded its victims, forcing them to commit sometimes-bestial acts against their fellow prisoners in order to survive.

For Levi, salvation came from his education. Interviewed by a German technocrat for work in the camp’s synthetic rubber program, Levi was chosen for this relatively easy labor because he spoke fluent German, including scientific terminology. Work in the warm camp laboratory offered Levi opportunities to pilfer equipment he could then trade to other prisoners for food and necessities. Levi also gained critical support from three prisoners who refused to do wicked and hateful acts. And he counted luck as essential for his survival: in the camp infirmary with scarlet fever in February 1945 as advancing Russian armies prepared to liberate the camp, Levi was not evacuated by the Nazis and shot to death like most Jewish prisoners.

After the war, Levi was haunted by the nightmare that the Holocaust would be ignored or forgotten. Ashamed that so many people whom he considered better than himself had perished, and wanting the world to understand the genocide in all its complexity so that people would never again tolerate such atrocities, he turned to writing about his experiences. Primo Levi, while revealing Nazi guilt, tirelessly grappled with his vision of individual choice and moral ambiguity in a hell designed to make the victims collaborate and persecute each other.

* Primo Levi, The Drowned and the Saved (New York: Vintage, 1989), pp. 43, 60. See also Levi, Survival in Auschwitz: The Nazi Assault on Humanity (London: Collier Books, 1961). These powerful testimonies are highly recommended.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

Question

Describe Levi’s experience at Auschwitz. How did camp prisoners treat each other? Why?

Question

What does Levi mean by the “gray zone”?

Question

Will a vivid historical memory of the Holocaust help to prevent future genocide?