A History of Western Society: Printed Page 68

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 71

Overseas Expansion

The development of the polis coincided with the growth of the Greek world in both wealth and numbers, bringing new problems. The increase in population created more demand for food than the land could supply. The resulting social and political tensions drove many people to seek new homes outside of Greece. In some cases the losers in a conflict within a polis were forced to leave. Other factors, largely intangible, played their part as well: the desire for a new start, a love of excitement and adventure, and curiosity about what lay beyond the horizon.

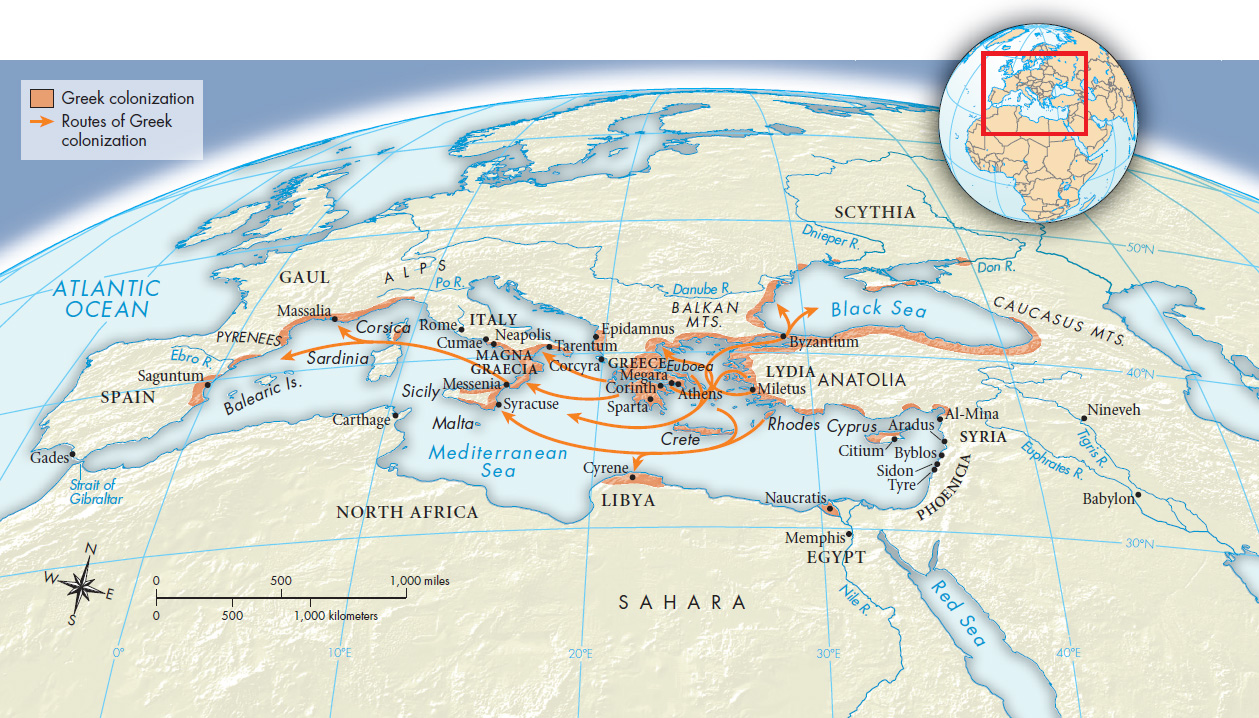

Greeks from the mainland and Ionia traveled throughout the Mediterranean, sailing in great numbers to Sicily and southern Italy, where there was ample space for expansion (Map 3.2). Here they established prosperous cities and often intermarried with local people. Some adventurous Greeks sailed farther west to Sardinia, France, Spain, and perhaps even the Canary Islands. In Sardinia they first established trading stations, and then permanent towns. From these new outposts Greek influence extended to southern France. The modern city of Marseilles, for example, began as a Greek colony and later sent settlers to southern Spain. In the far western Mediterranean the city of Carthage, established by the Phoenicians in the ninth century B.C.E., remained the dominant power. The Greeks traded with the Carthaginians but never conquered them.

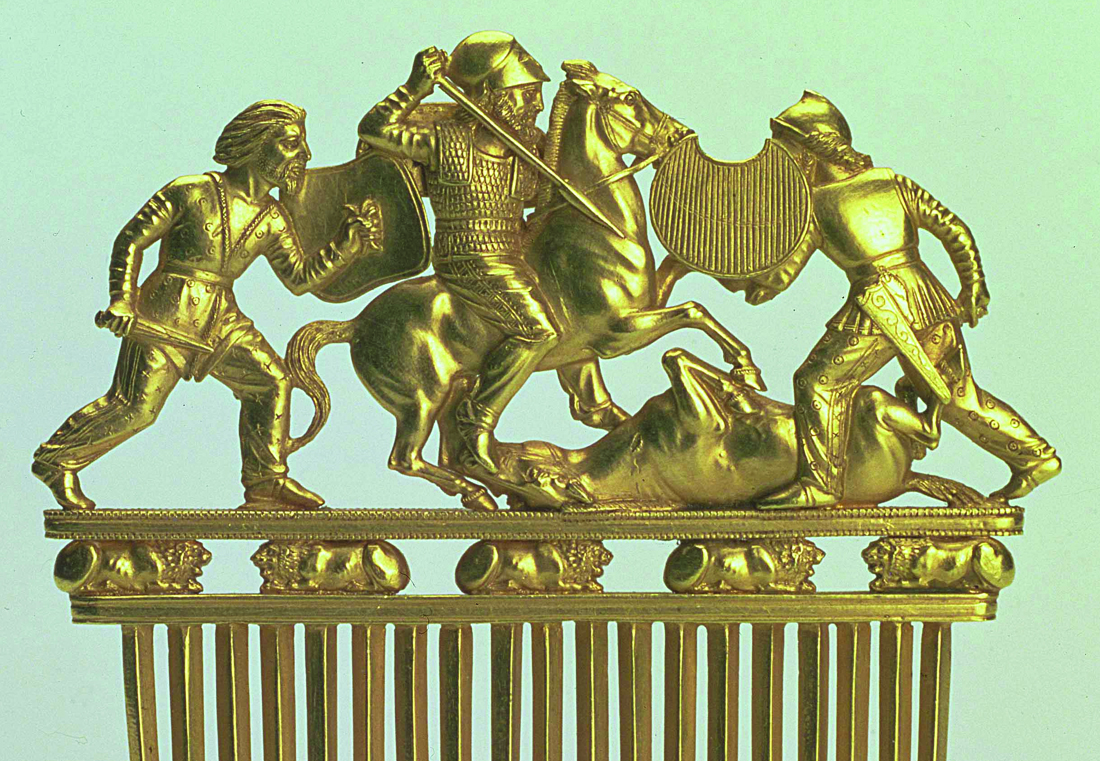

Colonization changed the entire Greek world, both at home and abroad. In economic terms the expansion of the Greeks created a much larger market for agricultural and manufactured goods. From the east, especially from the northern coast of the Black Sea, came wheat. In return flowed Greek wine and olive oil, which could not be produced in the harsher climate of the north. Greek-manufactured goods, notably rich jewelry and fine pottery, circulated from southern Russia to Spain. During the same period the Greeks adopted the custom of minting coins from metal, first developed in the kingdom of Lydia in Anatolia. Coins provided many advantages over barter: they allowed merchants to set the value of goods in a determined system, they could be stored easily, and they allowed for more complex exchanges than did direct barter.

Colonization presented the polis with a huge challenge, for it required organization and planning on an unprecedented scale. The colonizing city, called the metropolis, or “mother city,” first decided where to establish the colony, how to transport colonists to the site, and who would sail. Sometimes groups of people left willingly, and in other instances they left involuntarily after a civil war or other conflict. Then the metropolis collected and stored the supplies that the colonists would need both to feed themselves and to plant their first crop. All preparations ready, a leader, called an oikist, ordered the colonists to sail. Once the colonists landed, the oikist laid out the new polis, selected the sites of temples and public buildings, and established the government. Then he surrendered power to the new leaders. The colony was thereafter independent of the metropolis, a pattern that was quite different from most later systems of colonization. Colonization spread the polis and its values far beyond the shores of Greece.