Background and Motives of the Crusades

The medieval church’s attitude toward violence was contradictory. On the one hand, church councils threatened excommunication for anyone who attacked peasants, clerics, or merchants or destroyed crops and unfortified places, a movement termed the Peace of God. Councils also tried to limit the number of days on which fighting was permitted, prohibiting it on Sundays, on special feast days, and in the seasons of Lent and Advent. On the other hand, popes supported armed conflict against kings and emperors if this worked to their advantage, thus encouraging warfare among Christians. After a serious theological disagreement in 1054 split the Orthodox Church of Byzantium and the Roman Church of the West, the pope also contemplated invading the Byzantine Empire, an idea that subsequent popes considered as well.

Although conflicts in which Christians fought Christians were troubling to many thinkers, war against non-Christians was another matter. By the ninth century popes and other church officials encouraged war in defense of Christianity, promising spiritual benefits to those who died fighting. By the eleventh century these benefits were extended to all those who simply joined a campaign: their sins would be remitted without having to do penance, that is, without having to confess to a priest and carry out some action to make up for the sins. Around this time, Christian thinkers were developing the concept of purgatory, a place where those on their way to Heaven stayed for a while to do any penance they had not completed while alive. (Those on their way to Hell went straight there.) Engaging in holy war could shorten one’s time in purgatory, or, as many people understood the promise, allow one to head straight to paradise. Popes signified this by providing indulgences, grants with the pope’s name on them that lessened earthly penance and postmortem purgatory. Popes promised these spiritual benefits, and also provided financial support, for Christian armies in the reconquista in Spain and the Norman campaign against the Muslims in Sicily. Preachers communicated these ideas widely and told stories about warrior-saints who slew hundreds of enemies.

Religious devotion had long been expressed through pilgrimages to holy places, and these were increasingly described in military terms, as battles against the hardships along the way. Pilgrims to Jerusalem were often armed, so the line between pilgrimage and holy war on this particular route was increasingly blurred.

In the midst of these developments came a change in possession of Jerusalem. The Arabic Muslims who had ruled Jerusalem and the surrounding territory for centuries had allowed Christian pilgrims to travel freely, but in the late eleventh century the Seljuk (SEHL-jook) Turks took over Palestine, defeating both Arabic and Byzantine armies (Map 9.4). The emperor at Constantinople appealed to the West for support, asserting that the Turks would make pilgrimages to holy places more dangerous, and that the holy city of Jerusalem should be in Christian hands. The emperor’s appeal fit well with papal aims, and in 1095 Pope Urban II called for a great Christian holy war against the infidels — a term Christians and Muslims both used to describe the other. Urban offered indulgences to those who would fight for and regain the holy city of Jerusalem.

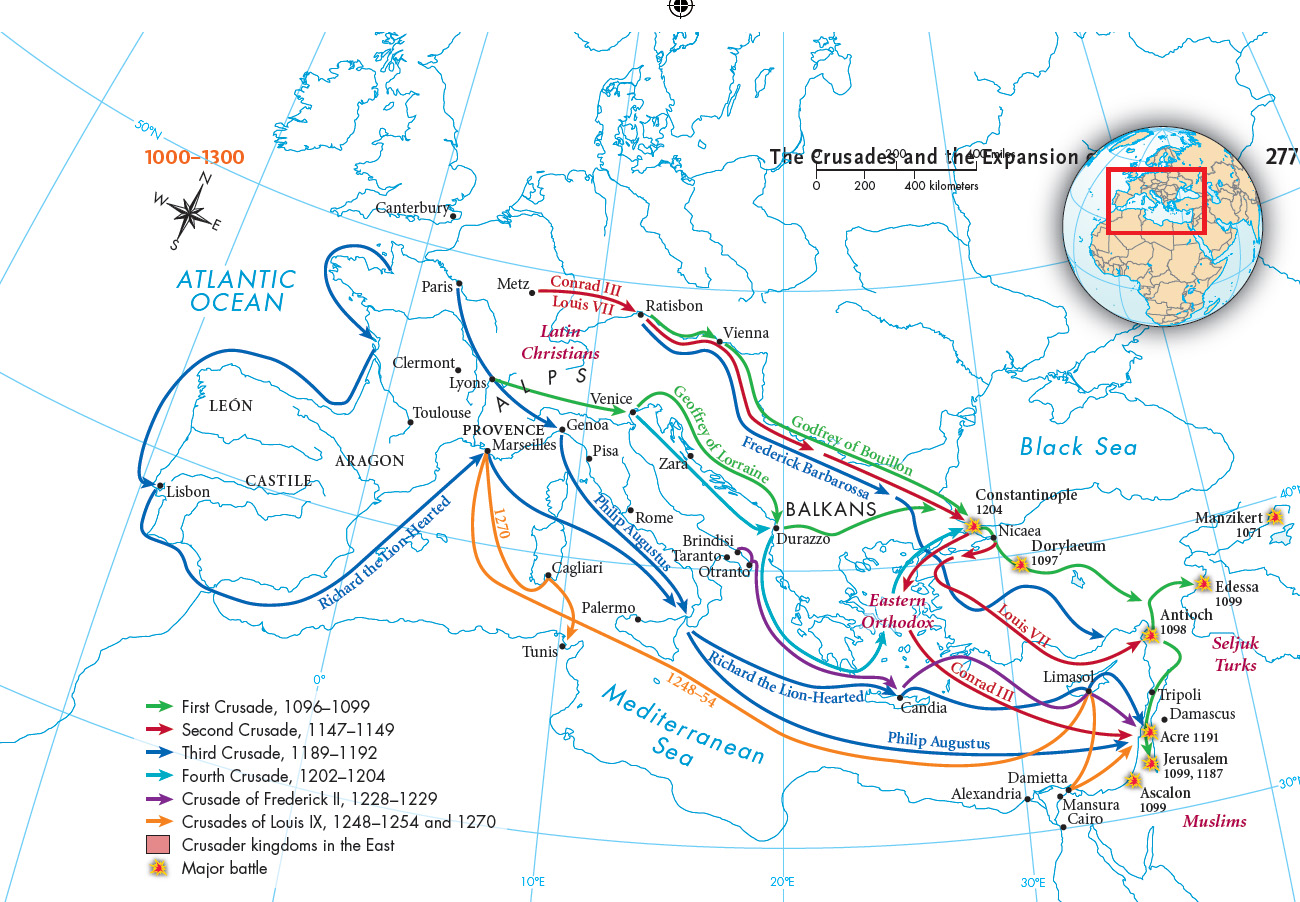

MAPPING THE PAST

ANALYZING THE MAP How were the results of the various Crusades shaped by the routes that the Crusaders took?

CONNECTIONS How did the routes and Crusader kingdoms offer opportunities for profit?