A History of Western Society: Printed Page 292

Living in the Past

Child’s Play

H istorians used to paint a grim picture of medieval childhood. Childhood, they argued, was not recognized as a distinct stage in life until at least the late eighteenth century, and children were raised harshly or received little parental attention because so many died. These views were derived largely from advice about raising children provided by priests and educators who advocated strict discipline and warned against coddling, and from portraits of children that showed them dressed as little adults.

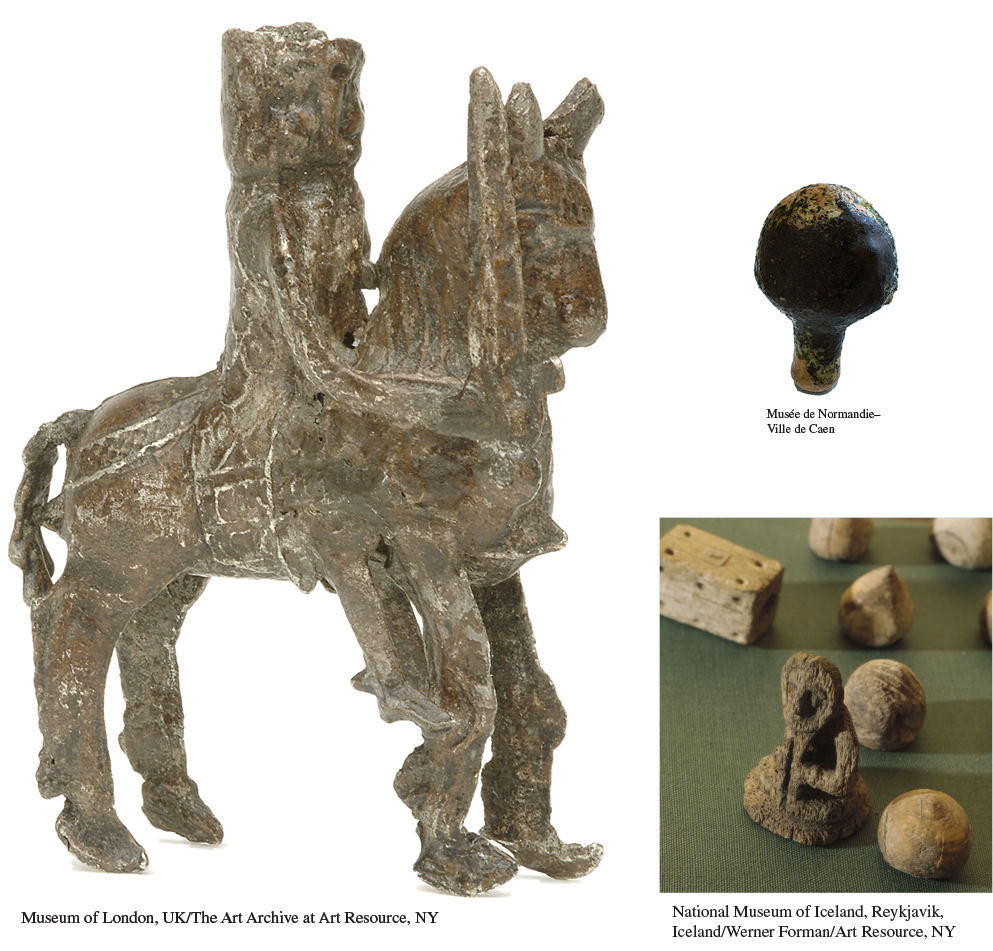

This bleak view has been relieved more recently by scholars using sources that reveal how children were actually treated. They have discovered that many parents showed great affection for their children and experienced deep grief when they died young. Parents left children to monasteries not because they were indifferent, but because they hoped thereby to ensure them a better material and spiritual future. Parents made toys for children: balls, dolls, rattles, boats, hobbyhorses, tops, and many other playthings. They tried to protect their children with religious amulets and pilgrimages to special shrines and sang them lullabies. Even practices that to us may seem cruel, such as tight swaddling, were motivated by a concern for the child’s safety and health at a time when most households had open fires, domestic animals wandered freely, and mothers and older siblings engaged in labor-

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- In the illustration of the mother and infant, how does the manuscript illuminator portray the relationship between parent and child? Does this support or challenge the notion that medieval parents treated their children coldly?

- How do the toys shown here prepare children for their later roles in life? Do these seem to be toys for nobles or for less elite children?

- How does the material from which these toys were made contribute to the fact that few have survived? What else might account for this? (To answer the latter question, think about your own toys: which ones were in good shape when you outgrew them, and which were not?)