A History of Western Society: Printed Page 366

Thinking Like a Historian

Humanist Learning

Renaissance humanists wrote often and forcefully about education, and learning was also a subject of artistic works shaped by humanist ideas. What did humanists see as the best course of study and the purpose of education, and how were these different for men and women?

| 1 | Peter Paul Vergerius, letter to Ubertinus of Padua, 1392. The Venetian scholar and church official Vergerius (1370–1445) advises the son of the ruler of Padua about the proper education for men. |

![]() We call those studies liberal which are worthy of a free man; those studies by which we attain and practise virtue and wisdom; that education which calls forth, trains and develops those highest gifts of body and of mind which ennoble men, and which are rightly judged to rank next in dignity to virtue only. . . .

We call those studies liberal which are worthy of a free man; those studies by which we attain and practise virtue and wisdom; that education which calls forth, trains and develops those highest gifts of body and of mind which ennoble men, and which are rightly judged to rank next in dignity to virtue only. . . .

| 2 | Leonardo Bruni, letter to Lady Baptista Malatesta, ca. 1405. The Florentine humanist and city official Leonardo Bruni advises the daughter of the duke of Urbino about the proper education for women. |

![]() There are certain subjects in which, whilst a modest proficiency is on all accounts to be desired, a minute knowledge and excessive devotion seem to be a vain display. For instance, subtleties of Arithmetic and Geometry are not worthy to absorb a cultivated mind, and the same must be said of Astrology. You will be surprised to find me suggesting (though with much more hesitation) that the great and complex art of Rhetoric should be placed in the same category. My chief reason is the obvious one, that I have in view the cultivation most fitting to a woman. To her neither the intricacies of debate nor the oratorical artifices of action and delivery are of the least practical use, if indeed they are not positively unbecoming. Rhetoric in all its forms — public discussion, forensic argument, logical fence, and the like — lies absolutely outside the province of woman. What Disciplines then are properly open to her? In the first place she has before her, as a subject peculiarly her own, the whole field of religion and morals. The literature of the Church will thus claim her earnest study. . . .

There are certain subjects in which, whilst a modest proficiency is on all accounts to be desired, a minute knowledge and excessive devotion seem to be a vain display. For instance, subtleties of Arithmetic and Geometry are not worthy to absorb a cultivated mind, and the same must be said of Astrology. You will be surprised to find me suggesting (though with much more hesitation) that the great and complex art of Rhetoric should be placed in the same category. My chief reason is the obvious one, that I have in view the cultivation most fitting to a woman. To her neither the intricacies of debate nor the oratorical artifices of action and delivery are of the least practical use, if indeed they are not positively unbecoming. Rhetoric in all its forms — public discussion, forensic argument, logical fence, and the like — lies absolutely outside the province of woman. What Disciplines then are properly open to her? In the first place she has before her, as a subject peculiarly her own, the whole field of religion and morals. The literature of the Church will thus claim her earnest study. . . .

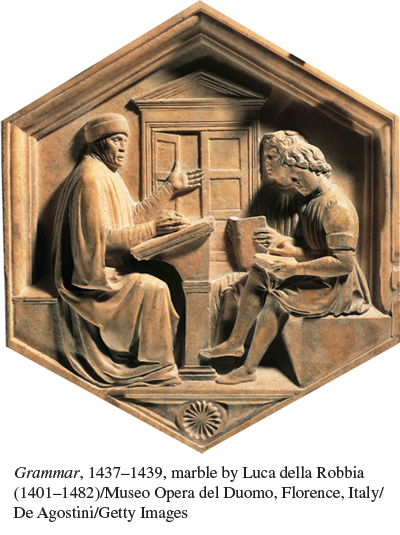

| 3 | Luca della Robbia, Grammar, 1437–1439. In this hexagonal panel made for the bell tower of the cathedral of Florence, Luca della Robbia conveys ideas about the course and goals of learning with the open classical door in the background. |

| 4 | Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, “Oration on the Dignity of Man,” 1486. Pico, the brilliant son of an Italian count and protégé of Lorenzo de’ Medici, wrote an impassioned summary of human capacities for learning that ends with this. |

![]() O sublime generosity of God the Father! O highest and most wonderful felicity of man! To him it was granted to have what he chooses, to be what he wills. At the moment when they are born, beasts bring with them from their mother’s womb, as Lucilius [the classical Roman author] says, whatever they shall possess. From the beginning or soon afterwards, the highest spiritual beings have been what they are to be for all eternity. When man came into life, the Father endowed him with all kinds of seeds and the germs of every way of life. Whatever seeds each man cultivates will grow and bear fruit in him. If these seeds are vegetative, he will be like a plant; if they are sensitive, he will become like the beasts; if they are rational, he will become like a heavenly creature; if intellectual, he will be an angel and a son of God. And if, content with the lot of no created being, he withdraws into the centre of his own oneness, his spirit, made one with God in the solitary darkness of the Father, which is above all things, will surpass all things. Who then will not wonder at this chameleon of ours, or who could wonder more greatly at anything else?

O sublime generosity of God the Father! O highest and most wonderful felicity of man! To him it was granted to have what he chooses, to be what he wills. At the moment when they are born, beasts bring with them from their mother’s womb, as Lucilius [the classical Roman author] says, whatever they shall possess. From the beginning or soon afterwards, the highest spiritual beings have been what they are to be for all eternity. When man came into life, the Father endowed him with all kinds of seeds and the germs of every way of life. Whatever seeds each man cultivates will grow and bear fruit in him. If these seeds are vegetative, he will be like a plant; if they are sensitive, he will become like the beasts; if they are rational, he will become like a heavenly creature; if intellectual, he will be an angel and a son of God. And if, content with the lot of no created being, he withdraws into the centre of his own oneness, his spirit, made one with God in the solitary darkness of the Father, which is above all things, will surpass all things. Who then will not wonder at this chameleon of ours, or who could wonder more greatly at anything else?

| 5 |

Cassandra Fedele, “Oration on Learning,” 1487. The Venetian Cassandra Fedele (1465–1558), the best- |

![]() I shall speak very briefly on the study of the liberal arts, which for humans is useful and honorable, pleasurable and enlightening since everyone, not only philosophers but also the most ignorant man, knows and admits that it is by reason that man is separated from beasts. For what is it that so greatly helps both the learned and the ignorant? What so enlarges and enlightens men’s minds the way that an education in and knowledge of literature and the liberal arts do? . . . But erudite men who are filled with the knowledge of divine and human things turn all their thoughts and considerations toward reason as though toward a target, and free their minds from all pain, though plagued by many anxieties. These men are scarcely subjected to fortune’s innumerable arrows and they prepare themselves to live well and in happiness. They follow reason as their leader in all things; nor do they consider themselves only, but they are also accustomed to assisting others with their energy and advice in matters public and private. . . .

I shall speak very briefly on the study of the liberal arts, which for humans is useful and honorable, pleasurable and enlightening since everyone, not only philosophers but also the most ignorant man, knows and admits that it is by reason that man is separated from beasts. For what is it that so greatly helps both the learned and the ignorant? What so enlarges and enlightens men’s minds the way that an education in and knowledge of literature and the liberal arts do? . . . But erudite men who are filled with the knowledge of divine and human things turn all their thoughts and considerations toward reason as though toward a target, and free their minds from all pain, though plagued by many anxieties. These men are scarcely subjected to fortune’s innumerable arrows and they prepare themselves to live well and in happiness. They follow reason as their leader in all things; nor do they consider themselves only, but they are also accustomed to assisting others with their energy and advice in matters public and private. . . .

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

- According to these sources, what should people learn? Why should they learn?

- Renaissance humanism has sometimes been viewed as opposed to religion, especially to the teachings of the Catholic Church at the time. Do these sources support this idea?

- How are the programs of study recommended for men and women similar? How and why are they different?

- How does the gender of the author shape his or her ideas about the human capacity for reason and learning?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Using the sources above, along with what you have learned in class and in this chapter, write a short essay that analyzes humanist learning. What were the goals and purposes of humanist education, and how were these different for men and women? How did these differences reflect Renaissance society more generally?

Sources: (1, 2) W. H. Woodward, ed. and trans., Vittorino da Feltre and Other Humanist Educators (London: Cambridge University Press, 1897), pp. 102, 106–107, 126–127; (4) Translated by Mary Martin McLaughlin, in The Portable Renaissance Reader, edited by James Bruce Ross and Mary Martin McLaughlin, copyright 1953, 1968, renewed © 1981 by Penguin Random House LLC. Used by permission of Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC; (5) Cassandra Fedele, Letters and Orations, ed. and trans. Diana Robin. Copyright © 2000 by The University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. Used with permission of the publisher.