A History of Western Society: Printed Page 448

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 432

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 449

Life in the Colonies

Many factors helped shape life in European colonies, including geographical location, pre-

Women played a crucial role in the emergence of colonial societies. The first explorers formed unions with native women, through coercion or choice, and relied on them as translators and guides and to form alliances with indigenous powers. As settlement developed, the character of each colony was influenced by the presence or absence of European women. Where women and children accompanied men, as in the British colonies and the Spanish mainland colonies, new settlements took on European languages, religion, and ways of life that have endured, with input from local cultures, to this day. Where European women did not accompany men, as on the west coast of Africa and most European outposts in Asia, local populations largely retained their own cultures, to which male Europeans acclimatized themselves. The scarcity of women in all colonies, at least initially, opened up opportunities for those who did arrive, leading one cynic to comment that even “a whore, if handsome, makes a wife for some rich planter.”15

It was not just the availability of Englishwomen that prevented Englishmen from forming unions with indigenous women. English cultural attitudes drew strict boundaries between “civilized” and “savage,” and even settlements of Christianized native peoples were segregated from the English. This was in strong contrast with the situation in New France, where royal officials initially encouraged French traders to form ties with indigenous people, including marrying local women. Assimilation of the native population was seen as one solution to the low levels of immigration from France.

The vast majority of women who crossed the Atlantic were captive Africans, constituting four-

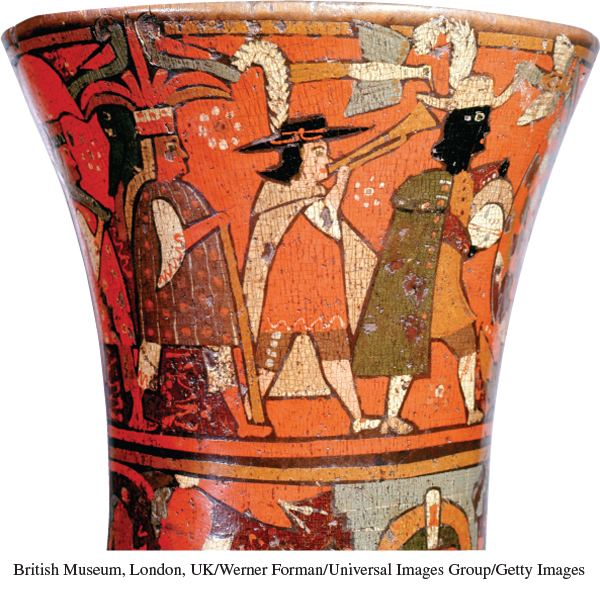

The mixing of indigenous peoples with Europeans and Africans created whole new populations and ethnicities and complex forms of identity (see Chapter 17). In Spanish America the word mestizo — métis in French — described people of mixed Native American and European descent. The blanket terms “mulatto” and “people of color” were used for those of mixed African and European origin. With its immense slave-