A History of Western Society: Printed Page 428

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 413

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 430

Chapter Chronology

The Trading States of Africa

By 1450 Africa had a few large empires along with hundreds of smaller states. From 1250 until its defeat by the Ottomans in 1517, the Mamluk Egyptian empire was one of the most powerful on the continent. Its capital, Cairo, was a center of Islamic learning and religious authority as well as a hub for Indian Ocean trade goods. Sharing in Cairo’s prosperity was the African highland state of Ethiopia, a Christian kingdom with scattered contacts with European rulers. On the east coast of Africa, Swahili-speaking city-states engaged in the Indian Ocean trade, exchanging ivory, rhinoceros horn, tortoise shells, and slaves for textiles, spices, cowrie shells, porcelain, and other goods. Peopled by confident and urbane merchants, cities like Kilwa, Malindi, Mogadishu, and Mombasa were known for their prosperity and culture.

Page 429

In the fifteenth century most of the gold that reached Europe came from the western part of the Sudan region in West Africa and from the Akan (AH-kahn) peoples living near present-day Ghana. Transported across the Sahara by Arab and African traders on camels, the gold was sold in the ports of North Africa. Other trading routes led to the Egyptian cities of Alexandria and Cairo, where the Venetians held commercial privileges.

Inland nations that sat astride the north-south caravan routes grew wealthy from this trade. In the mid-thirteenth century the kingdom of Mali emerged as an important player on the overland trade route, gaining prestige from its ruler Mansa Musa’s fabulous pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324/25. Mansa Musa reportedly came to the throne after the previous king failed to return from a naval expedition he led to explore the Atlantic Ocean. A document by a contemporary scholar, al-Umari, quoted Mansa Musa’s description of his predecessor as a man who “did not believe that the ocean was impossible to cross. He wished to reach the other side and was passionately interested in doing so.”3 After only one ship returned from an earlier expedition, the king set out himself at the head of a fleet of two thousand vessels, a voyage from which no one returned. Corroboration of these early expeditions is lacking, but this report underlines the wealth and ambition of Mali in this period. In later centuries the diversion of gold away from the trans-Sahara routes would weaken the inland states of Africa politically and economically.

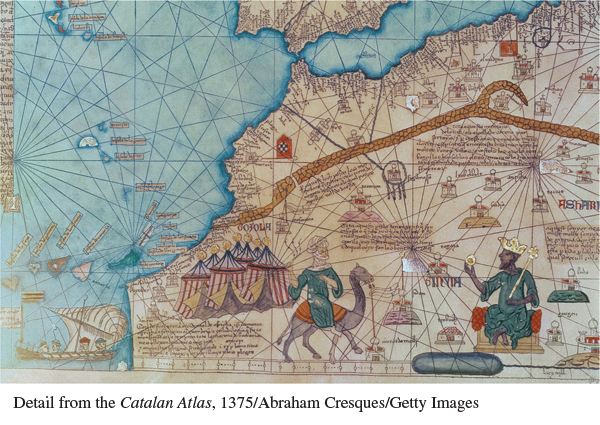

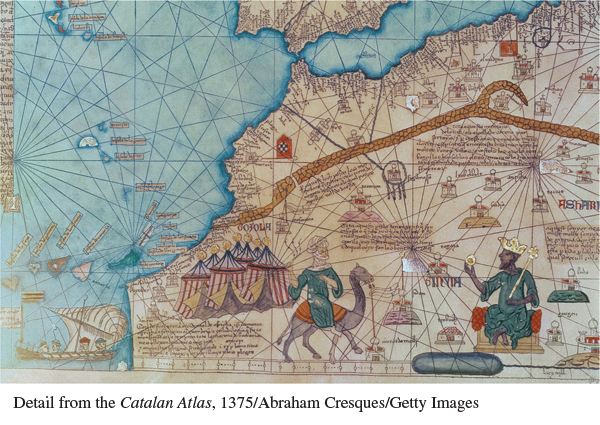

Detail from the Catalan Atlas, 1375 This detail from a medieval map depicts Mansa Musa (lower right), who ruled the powerful West African empire of Mali from 1312 to 1337. Musa’s golden crown and scepter, and the gold ingot he holds in his hand, testify to the empire’s wealth as well as to the European mapmakers’ interest in the precious metal mined in the area.

(Detail from the Catalan Atlas, 1375/Abraham Cresques/Getty Images)

Page 430

Gold was one important object of trade; slaves were another. Slavery was practiced in Africa, as it was virtually everywhere else in the world, long before the arrival of Europeans. Arab and African merchants took West African slaves to the Mediterranean to be sold in European, Egyptian, and Middle Eastern markets and also brought eastern Europeans — a major element of European slavery — to West Africa as slaves. In addition, Indian and Arab merchants traded slaves in the coastal regions of East Africa.

Legends about Africa played an important role in Europeans’ imagination of the outside world. They long cherished the belief in a powerful Christian nation in Africa ruled by a mythical king, Prester John, who was believed to be a descendant of one of the three kings who visited Jesus after his birth.