A History of Western Society: Printed Page 476

Living in the Past

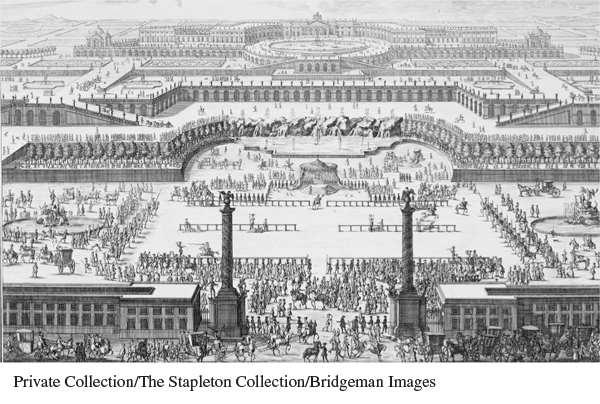

The Absolutist Palace

B y 1700 palace building had become a veritable obsession for European rulers. Their dramatic palaces symbolized the age of absolutist power, just as soaring Gothic cathedrals had expressed the idealized spirit of the High Middle Ages. With its classically harmonious, symmetrical, and geometric design, Versailles served as the model for the wave of palace building that began in the last decade of the seventeenth century. Royal palaces like Versailles were intended to overawe the people and proclaim their owners’ authority and power.

Located ten miles southwest of Paris, Versailles began as a modest hunting lodge built by Louis XIII in 1623. His son Louis XIV spent decades enlarging and decorating the original structure. Between 1668 and 1670 architect Louis Le Vau (luh VOH) enveloped the old building within a much larger one that still exists today. In 1682 the new palace became the official residence of the Sun King and his court, although construction continued until 1710, when the royal chapel was completed. At any one time, several thousand people occupied the bustling and crowded palace. The awesome splendor of the eighty-

In 1693 Charles XI of Sweden, having reduced the power of the aristocracy, ordered the construction of his Royal Palace, which dominates the center of Stockholm to this day. Another such palace was Schönbrunn, an enormous Viennese Versailles begun in 1695 by Emperor Leopold to celebrate Austrian military victories and Habsburg might. Shown at lower right is architect Joseph Bernhard Fischer von Erlach’s ambitious plan for Schönbrunn palace. Fischer’s plan emphasizes the palace’s vast size and its role as a site for military demonstrations. Ultimately, financial constraints resulted in a more modest building.

In central and eastern Europe the favorite noble servants of royalty became extremely rich and powerful, and they, too, built grandiose palaces in the capital cities. These palaces were in part an extension of the monarch, for they surpassed the buildings of less-

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- Compare these images. What did concrete objects and the manipulation of space accomplish for these rulers that mere words could not?

- What disadvantages might stem from using architecture as a political tool?

- Is the use of space and monumental architecture still a political tool in today’s world?