A History of Western Society: Printed Page 522

Thinking Like a Historian

The Enlightenment Debate on Religious Tolerance

Enlightenment philosophers questioned many aspects of European society, including political authority, social inequality, and imperialism. A major focus of their criticism was the dominance of the established church and the persecution of minority faiths. While many philosophers defended religious tolerance, they differed widely in their approaches to the issue.

| 1 | Moses Mendelssohn, “Reply to Lavater,” 1769. In 1769 Johann Caspar Lavater, a Swiss clergyman, called on Moses Mendelssohn to either refute proofs of Christianity publicly or submit to baptism. Mendelssohn’s reply is both a call for toleration and an affirmation of his religious faith. |

![]() It is, of course, the natural obligation of every mortal to diffuse knowledge and virtue among his fellow men, and to do his best to extirpate their prejudices and errors. One might think, in this regard, that it was the duty of every man publicly to oppose the religious opinions that he considers mistaken. But not all prejudices are equally harmful, and hence the prejudices we may think we perceive among our fellow men must not all be treated in the same way. Some are directly contrary to the happiness of the human race. . . .

It is, of course, the natural obligation of every mortal to diffuse knowledge and virtue among his fellow men, and to do his best to extirpate their prejudices and errors. One might think, in this regard, that it was the duty of every man publicly to oppose the religious opinions that he considers mistaken. But not all prejudices are equally harmful, and hence the prejudices we may think we perceive among our fellow men must not all be treated in the same way. Some are directly contrary to the happiness of the human race. . . .

Sometimes, however, the opinions of my fellow men, which in my belief are errors, belong to the higher theoretical principles which are too remote from practical life to do any direct harm; but, precisely because of their generality, they form the basis on which the nation that upholds them has built its moral and social system, and thus happen to be of great importance to this part of the human race. To oppose such doctrines in public, because we consider them prejudices, is to dig up the ground to see whether it is solid and secure, without providing any other support for the building that stands on it. Anyone who cares more for the good of humanity than for his own fame will be slow to voice his opinion about such prejudices, and will take care not to attack them outright without extreme caution.

| 2 | Voltaire, Treatise on Toleration, 1763. Voltaire, the prominent French philosophe, began his Treatise on Toleration by recounting the infamous trial of Jean Calas. Although all the evidence pointed toward suicide, the judges concluded that Calas had killed his son in order to prevent him from converting to Catholicism, and Calas was brutally executed in 1762. For Voltaire, the Calas affair was a battle between fanaticism and reason, extremism and moderation. |

![]() Some fanatic in the crowd cried out that Jean Calas had hanged his son Marc Antoine. The cry was soon repeated on all sides; some adding that the deceased was to have abjured Protestantism on the following day, and that the family and young Lavaisse had strangled him out of hatred of the Catholic religion. In a moment all doubt had disappeared. The whole town was persuaded that it is a point of religion with the Protestants for a father and mother to kill their children when they wish to change their faith.

Some fanatic in the crowd cried out that Jean Calas had hanged his son Marc Antoine. The cry was soon repeated on all sides; some adding that the deceased was to have abjured Protestantism on the following day, and that the family and young Lavaisse had strangled him out of hatred of the Catholic religion. In a moment all doubt had disappeared. The whole town was persuaded that it is a point of religion with the Protestants for a father and mother to kill their children when they wish to change their faith.

. . . There was not, and could not be, any evidence against the family; but a deluded religion took the place of proof. . . .

The daughters were taken from the mother and put in a convent. The mother, almost sprinkled with the blood of her husband, her eldest son dead, the younger banished, deprived of her daughters and all her property, was alone in the world, without bread, without hope, dying of the intolerable misery. Certain persons, having carefully examined the circumstances of this horrible adventure, were so impressed that they urged the widow, who had retired into solitude, to go and demand justice at the feet of the throne. . . .

At Paris reason dominates fanaticism, however powerful it be; in the provinces fanaticism almost always overcomes reason.

| 3 |

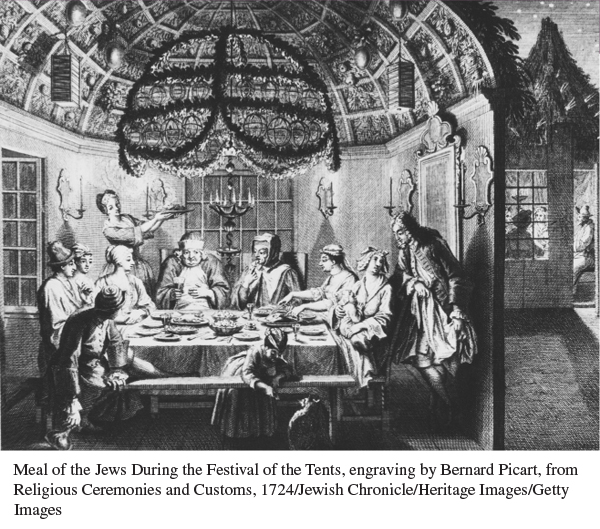

Bernard Picart, “Jewish Meal During the Feast of the Tabernacles,” from Ceremonies and Customs of All the Peoples of the World, 1724. Eighteenth- |

| 4 | Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Nathan the Wise, 1779. In this excerpt from Nathan the Wise, a play by German writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, the sultan Saladin asks a Jewish merchant named Nathan to tell him which is the true religion: Islam, Christianity, or Judaism. Nathan responds with a parable about a man who promised to leave the same opal ring, a guarantor of divine favor, to each of his three beloved sons. He then had two exact replicas of the ring made so that each son would believe he had inherited the precious relic. |

![]() NATHAN: Scarce was the father dead.

NATHAN: Scarce was the father dead.

When each one with his ring appears

Claiming each the headship of the house.

Inspections, quarrelling, and complaints ensue;

But all in vain, the veritable ring

Was not distinguishable —

(After a pause, during which he expects the Sultan’s answer)

Almost as indistinguishable as to us,

Is now — the true religion.

SALADIN: What? Is that meant as answer to my question?

NATHAN:’Tis meant but to excuse myself, because

I lack the boldness to discriminate between the rings,

Which the father by express intent had made

So that they might not be distinguished.

SALADIN: The rings! Don’t play with me.

I thought the faiths which I have named

Were easily distinguishable,

Even to their raiment, even to meat and drink.

NATHAN: But yet not as regards their proofs:

For do not all rest upon history, written or traditional?

And history can also be accepted

Only on faith and trust. Is it not so?

Now, whose faith and confidence do we least misdoubt?

That of our relatives? Of those whose flesh and blood we are,

Of those who from our childhood

Have lavished on us proofs of love,

Who ne’er deceived us, unless ’twere wholesome for us so?

How can I place less faith in my forefathers

Than you in yours? or the reverse?

Can I desire of you to load your ancestors with lies,

So that you contradict not mine? Or the reverse?

And to the Christian the same applies.

Is that not so?

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

- Based on these sources, what attitudes did eighteenth-

century Europeans manifest toward religions other than their own? Were such attitudes always negative? - What justifications did Enlightenment philosophers use to argue in favor of religious tolerance? Were arguments in favor of religious tolerance necessarily antireligious?

- Why did Judaism figure so prominently in debates about religious tolerance in eighteenth-

century Europe? In what ways do you think Mendelssohn’s experience as a Jew (Source 1) shaped his views on religious tolerance?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Using the sources above, along with what you have learned in class and in this chapter, compare and contrast the views on religious toleration presented in the sources. On what would the authors of these works have agreed? How did their arguments in favor of toleration differ? What explanation can you offer for the differences you note?

Sources: (1) Ritchie Robertson, ed., The German-