A History of Western Society: Printed Page 530

Living in the Past

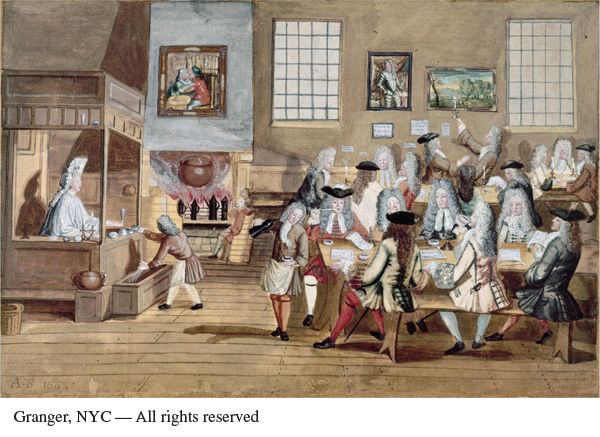

Coffeehouse Culture

C ustomers in today’s coffee shops may be surprised to learn that they are participating in a centuries-

European travelers in Istanbul were astonished at its inhabitants’ passion for coffee, which one described as “blacke as soote, and tasting not much unlike it.”* However, Italian merchants introduced coffee to Europe around 1600, and the first European coffee shop opened in Venice in 1645, soon followed by shops in Oxford, England, in 1650, London in 1652, and Paris in 1672. By the 1730s coffee shops had become so popular in London that one observer noted, “There are some people of moderate Fortunes, that lead their Lives mostly in Coffee-

Coffeehouses helped spread the ideas and values of the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment. They provided a new public space where urban Europeans could learn about and debate the issues of the day. Within a few years, each political party, philosophical sect, scientific society, and literary circle had its own coffeehouse, which served as a central gathering point for its members and an informal recruiting site for new ones. Coffeehouses self-

European coffeehouses also played a key role in the development of modern business, as their proprietors began to provide specialized commercial news to attract customers. Lloyd’s of London, the famous insurance company, got its start in the shipping lists published by coffeehouse owner Edward Lloyd in the 1690s. The streets around London’s stock exchange were crowded with coffeehouses where merchants and traders congregated to strike deals and hear the latest news.

Coffeehouses succeeded in Europe because they met a need common to politics, business, and intellectual life: the spread and sharing of information. In the late seventeenth century newspapers were rare and expensive, there were few banks to guarantee credit, and politics was limited to a tiny elite. To break through these constraints, people needed reliable information. The coffeehouse was an ideal place to acquire it, along with a new kind of stimulant that provided the energy and attention to fuel a lively discussion.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- What do the images shown here suggest about the customers of seventeenth-

and eighteenth- century coffeehouses? Who frequented these establishments? Who was excluded? - What limitations on the exchange of information existed in early modern Europe? Why were coffeehouses so useful as sites for exchanging information?

- What social role do coffeehouses play where you live? Do you see any continuities with the seventeenth-

and eighteenth- century coffeehouse?