A History of Western Society: Printed Page 554

Thinking Like a Historian

Rural Industry: Progress or Exploitation?

Eighteenth-

| 1 | Daniel Defoe’s observations of English industry Novelist and economic writer Daniel Defoe claimed that the labor of women and children in spinning and weaving brought in as much income as or more income than the man’s agricultural work, allowing the family to eat well and be warmly clothed. |

![]() Being a compleat prospect of the trade of this nation, as well the home trade as the foreign, 1728.

Being a compleat prospect of the trade of this nation, as well the home trade as the foreign, 1728.

[A] poor labouring man that goes abroad to his Day Work, and Husbandry, Hedging, Ditching, Threshing, Carting, &c. and brings home his Week’s Wages, suppose at eight Pence to twelve Pence a Day, or in some Counties less; if he has a Wife and three or four Children to feed, and who get little or nothing for themselves, must fare hard, and live poorly; ’tis easy to suppose it must be so.

But if this Man’s Wife and Children can at the same Time get Employment, if at next Door, or at the next Village there lives a Clothier, or a Bay Maker, or a stuff or Drugget Weaver;* the Manufacturer sends the poor Woman combed Wool, or carded Wool every Week to spin, and she gets eight Pence or nine Pence a day at home; the Weaver sends for her two little Children, and they work by the Loom, winding, filling quills, &c. and the two bigger Girls spin at home with their Mother, and these earn three Pence or four Pence a Day each: So that put it together, the Family at Home gets as much as the Father gets Abroad, and generally more.

This alters the Case extremely, the Family feels it, they all feed better, are cloth’d warmer, and do not so easily nor so often fall into Misery and Distress; the Father gets them Food, and the Mother gets them Clothes; and as they grow, they do not run away to be Footmen and Soldiers, Thieves and Beggars or sell themselves to the Plantations to avoid the Gaol and the Gallows, but have a Trade at their Hands, and every one can get their Bread.

| 2 | Anonymous, “The Clothier’s Delight.” Couched in the voice of the ruthless cloth merchant, this song from around 1700 expresses the bitterness and resentment textile workers felt against the low wages paid by employers. One can imagine a group of weavers gathered at the local tavern singing their protest on a rare break from work. |

![]() Of all sorts of callings that in England be

Of all sorts of callings that in England be

There is none that liveth so gallant as we;

Our trading maintains us as brave as a knight,

We live at our pleasure and take our delight;

We heapeth up richest treasure great store

Which we get by griping and grinding the poor.

And this is a way for to fill up our purse

Although we do get it with many a curse.

Throughout the whole kingdom, in country and town,

There is no danger of our trade going down,

So long as the Comber can work with his comb,

And also the Weaver weave with his lomb;

The Tucker and Spinner that spins all the year,

We will make them to earn their wages full dear.

And this is a way, etc.

| 3 |

Late- |

![]() Fire at Isaac Hardy’s, which burnt 6 lbs. of cotton, 5 pairs of stockings and set the cradle on fire, with a child in which was much burnt. It happened through the wife improvidently holding the candle under the cotton as it was drying.

Fire at Isaac Hardy’s, which burnt 6 lbs. of cotton, 5 pairs of stockings and set the cradle on fire, with a child in which was much burnt. It happened through the wife improvidently holding the candle under the cotton as it was drying.

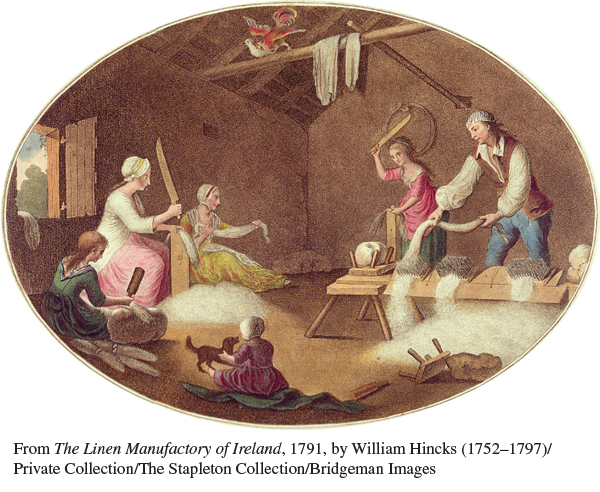

| 4 | The linen industry in Ireland. Many steps went into making textiles. Here the women are beating away the woody part of the flax plant so that the man can comb out the soft part. The combed fibers will then be spun into thread and woven into cloth by this family enterprise. |

| 5 |

Samuel Crompton’s memories of childhood labor. In his memoir, Samuel Crompton recalled his childhood labor in the cotton industry of the mid- |

![]() I recollect that soon after I was able to walk I was employed in the cotton manufacture. My mother used to bat the cotton wool on a wire riddle. It was then put into a deep brown mug with a strong ley of soap suds. My mother then tucked up my petticoats about my waist, and put me into the tub to tread upon the cotton at the bottom. When a second riddleful was batted I was lifted out, it was placed in the mug, and I again trod it down. This process was continued untill the mug became so full that I could no longer safely stand in it, when a chair was placed beside it, and I held on by the back. When the mug was quite full the soapsuds were poured off, and each separate dollop [i.e., lump] of wool well squeezed to free it from moisture. They were then placed on the bread-

I recollect that soon after I was able to walk I was employed in the cotton manufacture. My mother used to bat the cotton wool on a wire riddle. It was then put into a deep brown mug with a strong ley of soap suds. My mother then tucked up my petticoats about my waist, and put me into the tub to tread upon the cotton at the bottom. When a second riddleful was batted I was lifted out, it was placed in the mug, and I again trod it down. This process was continued untill the mug became so full that I could no longer safely stand in it, when a chair was placed beside it, and I held on by the back. When the mug was quite full the soapsuds were poured off, and each separate dollop [i.e., lump] of wool well squeezed to free it from moisture. They were then placed on the bread-

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

- What impression of cottage industry does the painting of the Irish linen industry in Source 4 present? How does this contrast with the impressions from the written sources?

- Do you think the personal accounts of a diary (Source 3) or a memoir (Source 5) are more reliable sources on rural industry than a social commentator’s opinion (Source 1) or a song (Source 2)? Why or why not?

- Who was involved in the work of rural textile manufacture, and what tasks did these workers perform? How does this division of labor resemble or differ from the household in which you grew up?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Using the sources above, along with what you have learned in class and in this chapter, write an essay assessing the impact of the putting-

Sources: (1) Daniel Defoe, A Plan of the English Commerce: Being a compleat prospect of the trade of this nation, as well the home trade as the foreign (London, 1728), pp. 90–91; (2) Paul Mantoux and Marjorie Vernon, eds., The Industrial Revolution in the Eighteenth Century: An Outline of the Beginnings of the Modern Factory System in England (1928; Abingdon, U.K.: Taylor and Francis, 2006), pp. 75–76; (3, 5) Ivy Pinchbeck, Women Workers and the Industrial Revolution, 1750–1850 (1930; Abingdon, U.K.: Frank Cass, 1977), p. 114.