A History of Western Society: Printed Page 568

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 568

Individuals in Society

Rebecca Protten

I n the mid-

Surviving documents refer to Rebecca as a “mulatto,” indicating a mixed European and African ancestry. A wealthy Dutch-

As a free woman, she continued to work as a servant for the van Beverhouts and to study the Bible and spread its message of spiritual freedom. In 1736 she met some missionaries for the Moravian Church, a German-

Rebecca soon took charge of the Moravians’ female missionary work. Every Sunday and every evening after work, she would walk for miles to lead meetings with enslaved and free black women. The meetings consisted of reading and writing lessons, prayers, hymns, a sermon, and individual discussions in which she encouraged her new sisters in their spiritual growth.

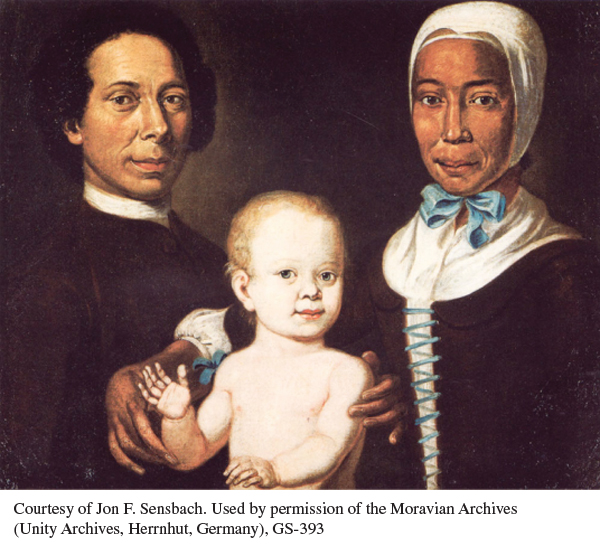

In 1738 Rebecca married a German Moravian missionary, Matthaus Freundlich, a rare but not illegal case of mixed marriage. The same year, her husband bought a plantation, with slaves, to serve as the headquarters of their mission work. The Moravians — and presumably Rebecca herself — wished to spread Christian faith among slaves and improve their treatment, but did not oppose the institution of slavery itself.

Authorities nonetheless feared that baptized and literate slaves would agitate for freedom, and they imprisoned Rebecca and Matthaus and tried to shut down the mission. Only the unexpected arrival on St. Thomas of German aristocrat and Moravian leader Count Zinzendorf saved the couple. Exhausted by their ordeal, they left for Germany in 1741 accompanied by their small daughter, but both father and daughter died soon after their arrival.

In Marienborn, a German center of the Moravian faith, Rebecca encountered other black Moravians, who lived in equality alongside their European brethren. In 1746 she married another missionary, Christian Jacob Protten, son of a Danish sailor and, on his mother’s side, grandson of a West African king. She and another female missionary from St. Thomas were ordained as deaconesses, probably making them the first women of color to be ordained in the Western Christian Church.

In 1763 Rebecca and her husband set out for her husband’s birthplace, the Danish slave fort at Christiansborg (in what is now Accra, Ghana) to establish a school for mixed-

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- Why did Moravian missionaries assign such an important leadership role to Rebecca? What particular attributes did she offer?

- Why did Moravians, including Rebecca, accept the institution of slavery instead of fighting to end it?

- What does Rebecca’s story teach us about the Atlantic world of the mid-

eighteenth century?