A History of Western Society: Printed Page 602

Chapter Chronology

Living in the Past

Page 602

Improvements in Childbirth

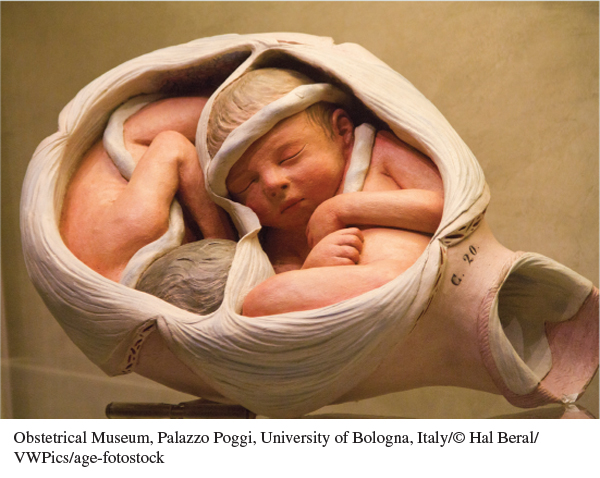

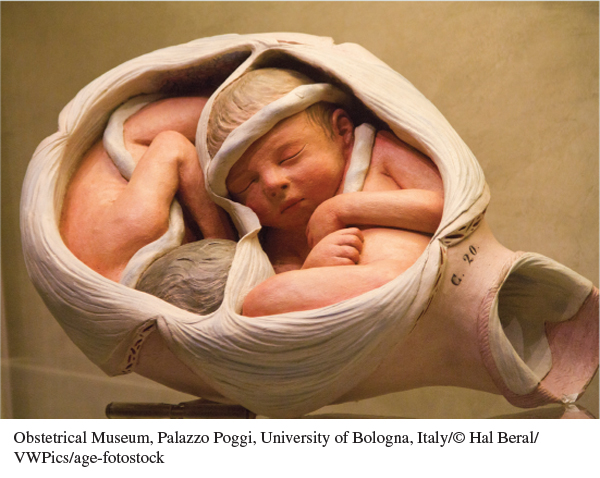

Life-size model showing twin fetuses.

(Obstetrical Museum, Palazzo Poggi, University of Bologna, Italy/© Hal Beral/VWPics/age-fotostock)

M ost women in eighteenth-century Europe gave birth to at least five or six children over their lifetimes. They were assisted in the arduous, often dangerous process of childbirth by friends, relatives, and, in many cases, professional midwives. Birth took place at home, sometimes with the aid of a birthing chair, such as the folding chair from Sicily shown bottom right.

The training and competency of midwives were often rudimentary, especially in the countryside. Enlightenment interest in education and public health helped inspire a movement across Europe to raise standards. One of its pioneers was Madame Angelique Marguerite Le Boursier du Coudray. Du Coudray herself had undergone a rigorous three-year apprenticeship and was a member of the Parisian surgeons’ guild. She set off on a mission to teach rural midwives in the French province of Auvergne.

Eighteenth-century birthing chair from Sicily.

(SSPL/Getty Images)

Du Coudray saw that her unlettered pupils learned through the senses, not through books. Thus she made, possibly for the first time in history, a life-size obstetrical model — a “machine” — out of fabric and stuffing for use in her classes. She reported, “I had . . . the students maneuver in front of me on a machine . . . which represented the pelvis of a woman, the womb, its opening, its ligaments, the conduit called the vagina, the bladder, and rectum intestine. I added [an artificial] child of natural size, whose joints were flexible enough to be able to be put in different positions.”* Now du Coudray could demonstrate the problems of childbirth, and each student could practice on the model in the “lab session.”

As her reputation grew, du Coudray sought to reach a national audience. In 1757 she published her Manual on the Art of Childbirth. The Manual incorporated her hands-on teaching method and served as a reference for students and graduates. In 1759 the government authorized du Coudray to carry her instruction “throughout the realm” and promised financial support.

Her classes brought women from surrounding villages to meet mornings and afternoons six days a week, with ample time to practice on the mannequin. After two to three months of instruction, Madame du Coudray and her entourage moved on. Teaching thousands of midwives, Madame du Coudray and her model may well have contributed to the decline in infant mortality and to the increase in population occurring in France in the eighteenth century — an increase she and her royal supporters fervently desired. Certainly she spread better knowledge about childbirth from the educated elite to the common people.

Page 603

Childbirth was traditionally a woman’s world that brought female relatives, friends, and the midwife to the laboring woman’s bedside, as shown in this Dutch painting from the late seventeenth century.

(The Newborn Baby, 1675, by Matthys Naiveu [1647–1726], [oil on canvas]/Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York, USA/Image source: Art Resource, NY)

“Incorrect method of delivery” from du Coudray’s Manual.

(Bibliothèque de la Faculté de Médecine, Paris, France/Archive Charmet/Bridgeman Images)

- How do you account for du Coudray’s remarkable success? What does her story suggest about women’s lives in this period, both within their families and in the economic realm? What kind of opportunities were available to women?

- What is painted on the Italian birthing chair where a woman’s head would rest during labor? What might this suggest about childbirth in this period?

- How might the Dutch painting of childbirth shown here differ if painted by a Western artist today?