A History of Western Society: Printed Page 631

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 605

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 631

Chapter Chronology

The Thermidorian Reaction and the Directory

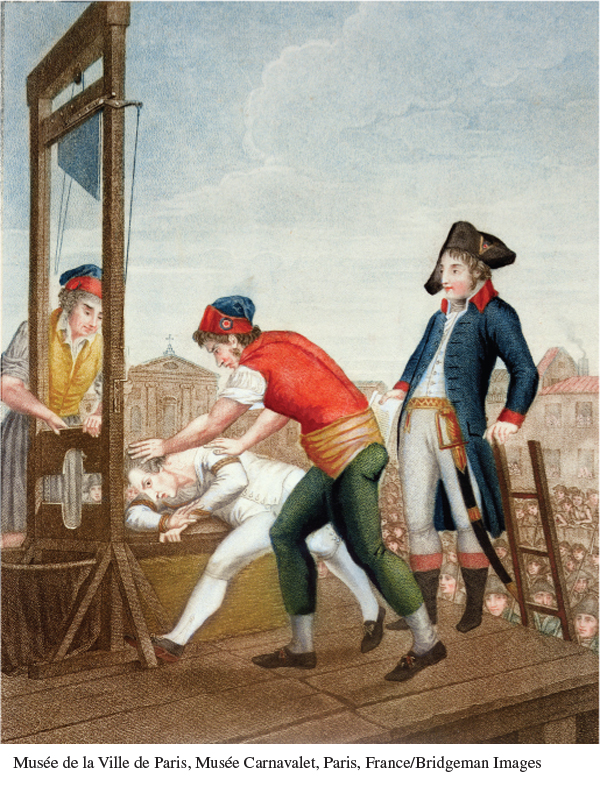

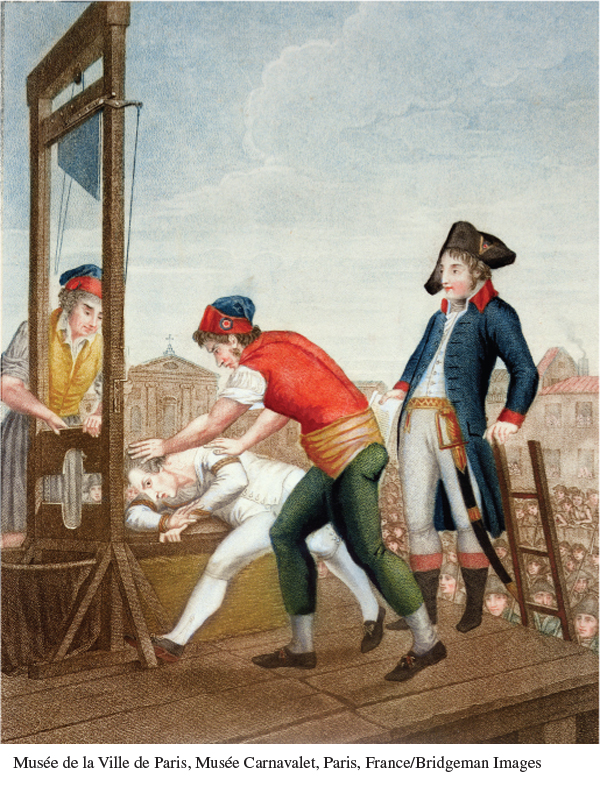

The success of French armies led the Committee of Public Safety to relax the emergency economic controls, but the Committee extended the political Reign of Terror. In March 1794 the revolutionary tribunal sentenced many of its critics to death. Two weeks later Robespierre sent long-standing collaborators who he believed had turned against him, including Danton, to the guillotine. In June 1794 a new law removed defendants’ right of legal counsel and criminalized criticism of the Revolution. A group of radicals and moderates in the Convention, knowing that they might be next, organized a conspiracy. They howled down Robespierre when he tried to speak to the National Convention on July 27, 1794 — a date known as 9 Thermidor according to France’s newly adopted republican calendar. The next day it was Robespierre’s turn to be guillotined.

The Execution of Robespierre After overseeing the Terror, during which thousands of men and women accused of being enemies of the Revolution faced speedy trial and execution, it was Maximilien Robespierre’s turn to face the guillotine on 9 Thermidor Year II (July 28, 1794).

(Musée de la Ville de Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, France/Bridgeman Images)

As Robespierre’s closest supporters followed their leader to the guillotine, the respectable middle-class lawyers and professionals who had led the liberal Revolution of 1789 reasserted their authority. This period of Thermidorian reaction, as it was called, hearkened back to the ideals of the early Revolution; the new leaders of government proclaimed an end to the revolutionary expediency of the Terror and the return of representative government, the rule of law, and liberal economic policies. In 1795 the National Convention abolished many economic controls, let prices rise sharply, and severely restricted the local political organizations through which the sans-culottes exerted their strength.

Page 634

In the same year, members of the National Convention wrote a new constitution to guarantee their economic position and political supremacy. As in previous elections, the mass of the population could vote only for electors who would in turn elect the legislators, but the new constitution greatly reduced the number of men eligible to become electors by instating a substantial property requirement. It also inaugurated a bicameral legislative system for the first time in the Revolution, with a Council of 500 serving as the lower house that initiated legislation and a Council of Elders (composed of about 250 members aged forty years or older) acting as the upper house that approved new laws. To prevent a new Robespierre from monopolizing power, the new Assembly granted executive power to a five-man body, called the Directory.

The Directory continued to support French military expansion abroad. War was no longer so much a crusade as a response to economic problems. Large, victorious French armies reduced unemployment at home. However, the French people quickly grew weary of the corruption and ineffectiveness that characterized the Directory. The trauma of years of military and political violence had alienated the public, and the Directory’s heavy-handed and opportunistic policies did not reverse the situation. This general dissatisfaction revealed itself clearly in the national elections of 1797, which returned a large number of conservative and even monarchist deputies who favored peace at almost any price. Two years later Napoleon Bonaparte ended the Directory in a coup d’état (koo day-TAH) and substituted a strong dictatorship for a weak one.