A History of Western Society: Printed Page 11

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 11

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 13

Environment and Mesopotamian Development

From the outset, geography had a profound effect on Mesopotamia, because here agriculture is possible only with irrigation. Consequently, the Sumerians and later civilizations built their cities along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and their branches. They used the rivers to carry agricultural and trade goods, and also to provide water for vast networks of irrigation channels.

The Tigris and Euphrates flow quickly at certain times of the year and carry silt down from the mountains and hills, causing floods. To prevent major floods, the Sumerians created massive hydraulic projects, including reservoirs, dams, and dikes as well as canals. In stories written later, they described their chief god, Enlil, as “the raging flood which has no rival,” and believed that at one point there had been a massive flood, a tradition that also gave rise to the biblical story of Noah:

A flood will sweep over the cult-

To destroy the seed of mankind . . .

Is the decision, the word of the assembly of the gods.1

Judging by historical records, however, actual destructive floods were few.

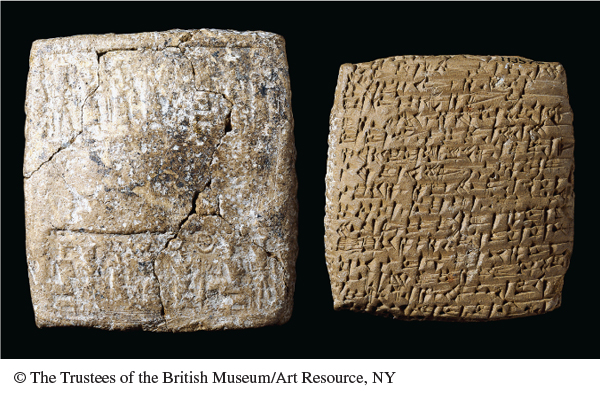

In addition to water and transport, the rivers supplied fish, a major element of the Sumerian diet, and reeds, which were used for making baskets and writing implements. The rivers also provided clay, which was hardened to create bricks, the Sumerians’ primary building material in a region with little stone. Clay was fired into pots, and inventive artisans developed the potter’s wheel so that they could make pots that were stronger and more uniform than those made by earlier methods of coiling ropes of clay. The potter’s wheel in turn appears to have led to the introduction of wheeled vehicles sometime in the fourth millennium B.C.E. Exactly where they were invented is hotly contested, but Sumer is one of the first locations in which they appeared. Wheeled vehicles, pulled by domesticated donkeys, led to road building, which facilitated settlement, trade, and conquest, although travel and transport by water remained far easier.

Cities and villages in Sumer and farther up the Tigris and Euphrates traded with one another, and even before the development of writing or kings, it appears that colonists sometimes set out from one city to travel hundreds of miles to the north or west to found a new city or to set up a community in an existing center. These colonies might well have provided the Sumerian cities with goods, such as timber and metal ores, that were not available locally. The cities of the Sumerian heartland continued to grow and to develop governments, and each one came to dominate the surrounding countryside, becoming city-

The city-

By 2500 B.C.E. there were more than a dozen city-