A History of Western Society: Printed Page 13

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 13

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 15

The Invention of Writing and the First Schools

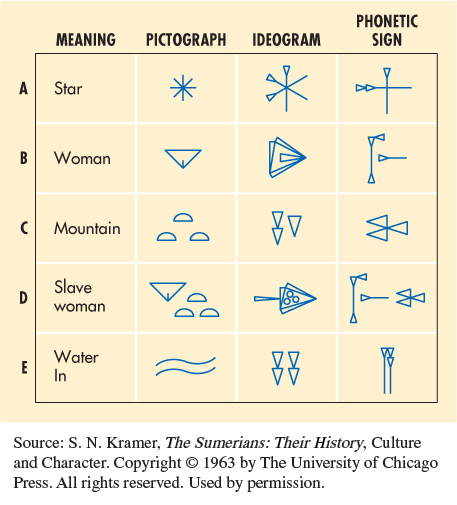

The origins of writing probably go back to the ninth millennium B.C.E., when Near Eastern peoples used clay tokens as counters for record keeping. By the fourth millennium, people had realized that impressing the tokens on clay, or drawing pictures of the tokens on clay, was simpler than making tokens. This breakthrough in turn suggested that more information could be conveyed by adding pictures of still other objects. The result was a complex system of pictographs in which each sign pictured an object, such as “star” (line A of Figure 1.1). These pictographs were the forerunners of the Sumerian form of writing known as cuneiform (kyou-

Scribes could combine pictographs to express meaning. For example, the sign for woman (line B) and the sign for mountain (line C) were combined, literally, into “mountain woman” (line D), which meant “slave woman” because the Sumerians regularly obtained their slave women from wars against enemies in the mountains. Pictographs were initially limited in that they could not represent abstract ideas, but the development of ideograms — signs that represented ideas — made writing more versatile. Thus the sign for star could also be used to indicate heaven, sky, or even god. The real breakthrough came when scribes started using signs to represent sounds. For instance, the symbol for “water” (two parallel wavy lines) could also be used to indicate “in,” which sounded the same as the spoken word for “water” in Sumerian.

The development of the Sumerian system of writing was piecemeal, with scribes making changes and additions as they were needed. The system became so complicated that scribal schools were established, which by 2500 B.C.E. flourished throughout Sumer. Students at the schools were all male, and most came from families in the middle range of urban society. Each school had a master, teachers, and monitors. Discipline was strict, and students were caned for sloppy work and misbehavior. One graduate of a scribal school had few fond memories of the joy of learning:

My headmaster read my tablet, said:

“There is something missing,” caned me.

. . .

The fellow in charge of silence said:

“Why did you talk without permission,” caned me.

The fellow in charge of the assembly said:

“Why did you stand at ease without permission,” caned me.2

Scribal schools were primarily intended to produce individuals who could keep records of the property of temple officials, kings, and nobles. Thus writing first developed as a way to enhance the growing power of elites, not to record speech, although it later came to be used for that purpose, and the stories of gods, kings, and heroes were also written down. Hundreds of thousands of hardened clay tablets have survived from ancient Mesopotamia, and from them historians have learned about many aspects of life, including taxes and wages. Sumerians wrote numbers as well as words on clay tablets, and some surviving tablets show multiplication and division problems.

Mathematics was not just a theoretical matter to the people living in Mesopotamia, because the building of cities, palaces, temples, and canals demanded practical knowledge of geometry and trigonometry.