A History of Western Society: Printed Page 22

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 21

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 23

The Nile and the God-King

The Greek historian and traveler Herodotus (heh-

Hail to thee, O Nile, that issues from the earth and comes to keep Egypt alive! . . .

He that waters the meadows which Re [Ra] created,

He that makes to drink the desert . . .

He who makes barley and brings emmer [wheat] into being . . .

He who brings grass into being for the cattle . . .

He who makes every beloved tree to grow . . .

O Nile, verdant art thou, who makest man and cattle to live.4

The Egyptians based their calendar on the Nile, dividing the year into three four-

Through the fertility of the Nile and their own hard work, Egyptians produced an annual agricultural surplus, which in turn sustained a growing and prosperous population. The Nile also unified Egypt. The river was the region’s principal highway, promoting communication and trade throughout the valley.

Egypt was fortunate in that it was nearly self-

The political power structures that developed in Egypt came to be linked with the Nile. Somehow the idea developed that a single individual, a king, was responsible for the rise and fall of the Nile. This belief came about before the development of writing in Egypt, so, as with the growth of priestly and royal power in Sumer, the precise details of its origins have been lost. The king came to be viewed as a descendant of the gods, and thus as a god himself. (See “Thinking Like a Historian: Addressing the Gods.”)

Political unification most likely proceeded slowly, but stories told about early kings highlighted one who had united Upper Egypt — the upstream valley in the south — and Lower Egypt — the delta area of the Nile that empties into the Mediterranean Sea — into a single kingdom around 3100 B.C.E. In some sources he is called Narmer and in other sources Menes, but his fame as a unifier is the same, whatever his name, and he is generally depicted in carvings and paintings wearing the symbols of the two kingdoms. Historians later divided Egyptian history into dynasties, or families of kings. For modern historical purposes, however, it is more useful to divide Egyptian history into periods (see “Periods of Egyptian History,” below). The political unification of Egypt in the Archaic Period (3100–2660 B.C.E.) ushered in the period known as the Old Kingdom (2660–2180 B.C.E.), an era remarkable for prosperity and artistic flowering.

Periods of Egyptian History

| Dates | Period | Significant Events |

| 3100–2660 B.C.E. | Archaic | Unification of Egypt |

| 2660–2180 B.C.E. | Old Kingdom | Construction of the pyramids |

| 2180–2080 B.C.E. | First Intermediate | Political disunity |

| 2080–1640 B.C.E. | Middle Kingdom | Recovery and political stability |

| 1640–1570 B.C.E. | Second Intermediate | Hyksos migrations; struggles for power |

| 1570–1070 B.C.E. | New Kingdom | Creation of an Egyptian empire; growth in wealth |

| 1070–712 B.C.E. | Third Intermediate | Political fragmentation and conquest by outsiders (see Chapter 2) |

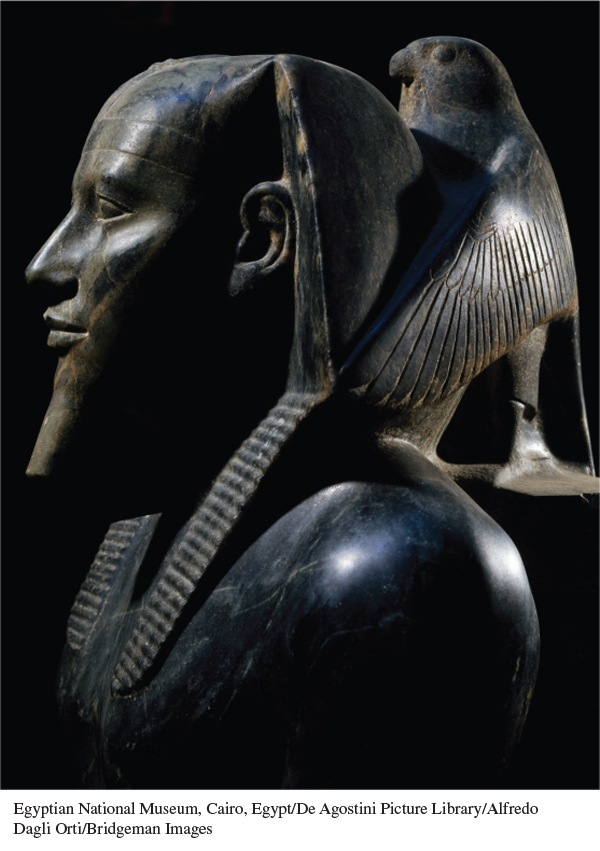

The focal point of religious and political life in the Old Kingdom was the king, who commanded wealth, resources, and people. The king’s surroundings had to be worthy of a god, and only a magnificent palace was suitable for his home; in fact, the word pharaoh, which during the New Kingdom came to be used for the king, originally meant “great house.” Just as the kings occupied a great house in life, so they reposed in great pyramids after death. Built during the Old Kingdom, these massive stone tombs contained all the things needed by the king in his afterlife. The pyramid also symbolized the king’s power and his connection with the sun-

To ancient Egyptians, the king embodied the concept of ma’at, a cosmic harmony that embraced truth, justice, and moral integrity. Ma’at gave the king the right, authority, and duty to govern. To the people, the king personified justice and order — harmony among themselves, nature, and the divine.

Kings did not always live up to this ideal, of course. The two parts of Egypt were difficult to hold together, and several times in Egypt’s long history there were periods of disunity, civil war, and chaos. During the First Intermediate Period (2180–2080 B.C.E.), rulers of various provinces asserted their independence from the king, and Upper and Lower Egypt were ruled by rival dynasties. There is evidence that the Nile’s floods were unusually low during this period because of drought, which contributed to instability just as it helped bring down the Akkadian empire. Warrior-