A History of Western Society: Printed Page 29

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 31

Individuals in Society

Hatshepsut and Nefertiti

E gyptians understood the pharaoh to be an avatar of the god Horus, the source of law and morality, and the mediator between gods and humans. The pharaoh’s connection with the divine stretched to members of his family, so that his siblings and children were also viewed as divine in some ways. Because of this, a pharaoh often took his sister or half-

The familial connection with the divine allowed a handful of women to rule in their own right in Egypt’s long history. We know the names of four female pharaohs, of whom the most famous was Hatshepsut (r. ca. 1479–ca. 1458 B.C.E.), the sister and wife of Thutmose II. After he died, she served as regent — adviser and co-

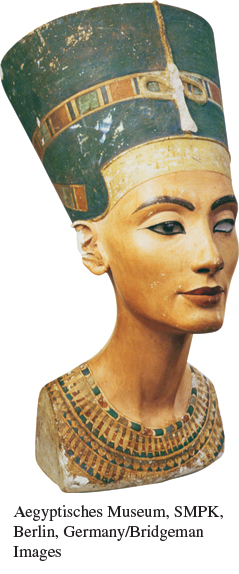

Though female pharaohs were very rare, many royal women had power through their position as “Great Royal Wives.” The most famous was Nefertiti, the wife of Akhenaton. Her name means “the perfect (or beautiful) woman has come,” and inscriptions also give her many other titles. Nefertiti used her position to spread the new religion of the sun-

Together Nefertiti and Akhenaton built a new palace and capital city at Akhetaton, the present Amarna, away from the old centers of power. There they developed the cult of Aton to the exclusion of the traditional deities. Nearly the only literary survival of their religious belief is the “Hymn to Aton,” which declares Aton to be the only god. It describes Nefertiti as “the great royal consort whom he, Akhenaton, loves. The mistress of the Two Lands, Upper and Lower Egypt.”

Nefertiti is often shown as being the same size as her husband, and in some inscriptions she is performing religious rituals that would normally have been carried out only by the pharaoh. The exact details of her power are hard to determine, however. An older theory held that her husband removed her from power, though there is also speculation that after his death she may have ruled secretly in her own right under a different name. Her tomb has long since disappeared. In the last decade individual archaeologists have claimed that several different mummies were Nefertiti, but most scholars dismiss these claims. Because her parentage is not known for certain, DNA testing such as that done on Tutankhamon’s corpse would not reveal whether any specific mummy was Nefertiti.

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- Why might it have been difficult for Egyptians to accept a female ruler?

- What opportunities do hereditary monarchies such as that of ancient Egypt provide for women? How does this fit with gender hierarchies in which men are understood as superior?