A History of Western Society: Printed Page 674

Thinking Like a Historian

Making the Industrialized Worker

Looking back from the vantage point of the 1820s and 1830s, contemporary observers saw in early industrialization a process that was as much about social transformation as it was about technological transformation—

| 1 | Peter Gaskell, The Manufacturing Population of England: Its Moral, Social, and Physical Conditions, and the Changes Which Have Arisen from the Use of Steam Machinery, 1833. In this excerpt, Peter Gaskell sketches the moral, social, and physical conditions of English workers before industrialization took hold, linking these characteristics to preindustrial work conditions. |

![]() Prior to the year 1760, manufactures were in a great measure confined to the demands of the home market. At this period, and down to 1800 . . . the majority of the artisans engaged in them had laboured in their own houses, and in the bosoms of their families. . . .

Prior to the year 1760, manufactures were in a great measure confined to the demands of the home market. At this period, and down to 1800 . . . the majority of the artisans engaged in them had laboured in their own houses, and in the bosoms of their families. . . .

These were, undoubtedly, the golden times of manufactures, considered in reference to the character of the labourers. By all the processes being carried on under a man’s own roof, he retained his individual respectability; he was kept apart from associations that might injure his moral worth, whilst he generally earned wages which were sufficient not only to live comfortably upon, but which enabled him to rent a few acres of land; thus joining in his own person two classes, that are now daily becoming more and more distinct. . . .

Thus, removed from many of those causes which universally operate to the deterioration of the moral character of the labouring man, when brought into large towns . . . the small farmer, spinner, or hand-

| 2 |

Richard Guest, A Compendious History of the Cotton- |

![]() The progress of the Cotton Manufacture introduced great changes into the manners and habits of the people. The operative workmen being thrown together in great numbers had their faculties sharpened and improved by constant communication. Conversation wandered over a variety of topics not before essayed; the questions of Peace and War, which interested them importantly, inasmuch as they might produce a rise or fall of wages, became highly interesting, and this brought them into the vast field of politics and discussions on the character of their Government, and the men who composed it. They took a greater interest in the defeats and victories of their country’s arms, and from being only a few degrees above their cattle in the scale of intellect, they became Political Citizens. . . .

The progress of the Cotton Manufacture introduced great changes into the manners and habits of the people. The operative workmen being thrown together in great numbers had their faculties sharpened and improved by constant communication. Conversation wandered over a variety of topics not before essayed; the questions of Peace and War, which interested them importantly, inasmuch as they might produce a rise or fall of wages, became highly interesting, and this brought them into the vast field of politics and discussions on the character of their Government, and the men who composed it. They took a greater interest in the defeats and victories of their country’s arms, and from being only a few degrees above their cattle in the scale of intellect, they became Political Citizens. . . .

The facility with which the Weavers changed their masters, the constant effort to find out and obtain the largest remuneration for their labour, the excitement to ingenuity which the higher wages for fine manufactures and skillful workmanship produced, and a conviction that they depended mainly on their own exertions, produced in them that invaluable feeling, a spirit of freedom and independence, and that guarantee for good conduct and improvement of manners, a consciousness of the value of character and of their own weight and importance.

| 3 |

Living conditions of the working class, 1845. As middle- |

![]() QUESTION: What is your usual experience regarding the cleanliness of these classes?

QUESTION: What is your usual experience regarding the cleanliness of these classes?

DR. BLUEMNER: Bad! Mother has to go out to work, and can therefore pay little attention to the domestic economy, and even if she makes an effort, she lacks time and means. A typical woman of this kind has four children, of whom she is still suckling one, she has to look after the whole household, to take food to her husband at work, perhaps a quarter of a mile away on a building site; she therefore has no time for cleaning and then it is such a small hole inhabited by so many people. The children are left to themselves, crawl about the floor or in the streets, and are always dirty; they lack the necessary clothing to change more often, and there is no time or money to wash these frequently. There are, of course, gradations; if the mother is healthy, active and clean, and if the poverty is not too great, then things are better.

| 4 |

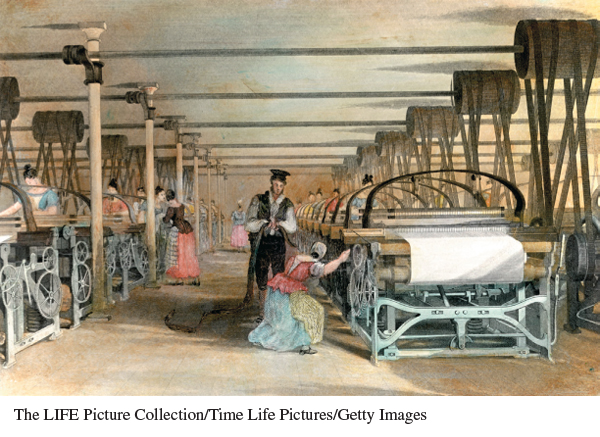

Power loom weaving, 1834. This engraving shows adult women operating power looms under the supervision of a male foreman, and it accurately reflects both the decline of family employment and the emergence of a gender- |

| 5 | Robert Owen, A New View of Society, 1831. Manufacturer and social reformer Robert Owen was also interested in the lessons of the early years of industrialization. He wished not to defend or decry industrialization, but to apply those lessons to the design and operation of his textile factory at New Lanark, Scotland. |

![]() The system of receiving apprentices from public charities was abolished; permanent settlers with large families were encouraged, and comfortable houses built for their accommodation. The practice of employing children in the mills, of six, seven, and eight years of age, was discontinued, and their parents advised to allow them to acquire health and education until they were ten years old. . . .

The system of receiving apprentices from public charities was abolished; permanent settlers with large families were encouraged, and comfortable houses built for their accommodation. The practice of employing children in the mills, of six, seven, and eight years of age, was discontinued, and their parents advised to allow them to acquire health and education until they were ten years old. . . .

[A]ttention was given to the domestic arrangements of the community. Their houses were rendered more comfortable, their streets were improved, the best provisions were purchased, and sold to them at low rates. . . .

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

- How does Richard Guest’s characterization of preindustrial workers and conditions in Source 2 compare to Peter Gaskell’s in Source 1? Why did Gaskell think industrialization would harm workers’ morals while Guest saw it as a force for moral improvement?

- Early-

nineteenth- century artists produced many images of the new factories. How would you describe the textile mill shown in Source 4? - According to the German doctor in Source 3, what challenges confronted working-

class women in their daily lives? To what extent does he seem to blame the women themselves for their situation? How might observations like these have affected the new sexual division of labor discussed in the text? - In what ways were Robert Owen’s innovations (Source 5) a response to the negative impacts of industrialization highlighted by the German doctor (Source 3)?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Using the sources above, along with what you have learned in class and in this chapter, create a comparison of industrial and preindustrial conditions, written from the perspective of a nineteenth-

Sources: (1) Peter Gaskell, The Manufacturing Population of England: Its Moral, Social, and Physical Conditions, and the Changes Which Have Arisen from the Use of Steam Machinery (London: Baldwin and Cradock, 1833), pp. 15–16, 18; (2) E. Royston Pike, Human Documents of the Industrial Revolution in Britain (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1970), pp. 26–28; (3) Laura L. Frader, ed., The Industrial Revolution: A History in Documents (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 85–86; (5) Pike, Human Documents of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, pp. 37–42.