A History of Western Society: Printed Page 701

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 670

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 698

Chapter Chronology

Romanticism in Art and Music

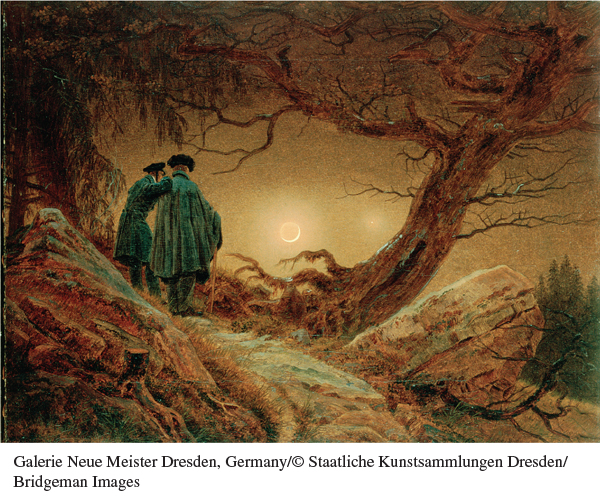

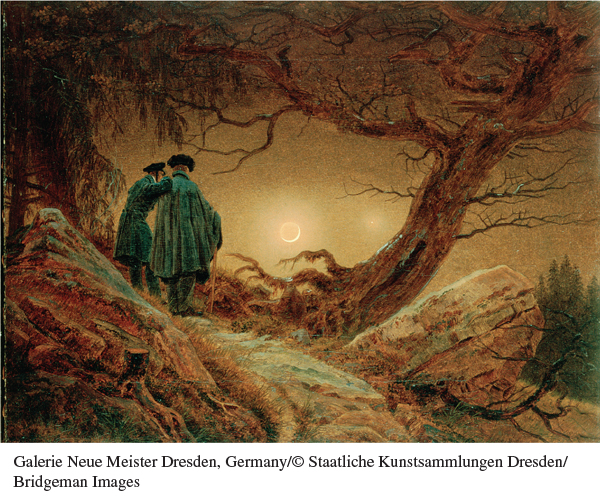

Romantic concerns with nature, history, and the imagination extended well beyond literature, into the realms of art and music. France’s Eugène Delacroix (oo-ZHEHN deh-luh-KWAH) (1798–1863), one of Romanticism’s greatest artists, painted dramatic, colorful scenes that stirred the emotions. Delacroix was fascinated with remote and exotic subjects, whether lion hunts in Morocco or dreams of languishing, sensuous women in a sultan’s harem. The famous German painter Casper David Friedrich (1774–1840) preferred somber landscapes of ruined churches or remote arctic shipwrecks, which captured the divine presence in natural forces.

Casper David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon, 1820 Friedrich’s reverence for the mysterious powers of nature radiates from this masterpiece of Romantic art. The painting shows two relatively small, anonymous figures mesmerized by the sublime beauty of the full moon. Viewers of the painting, positioned by the artist to look over the shoulders of the men, are likewise compelled to experience nature’s wonder. In a subtle expression of the connection between Romanticism and political reform, Friedrich has clothed the men in old-fashioned, traditional German dress, which radical students had adopted as a form of protest against the repressive conservatism of the post-Napoleonic era.

(Galerie Neue Meister Dresden, Germany/© Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden/Bridgeman Images)

In England the Romantic painters Joseph M. W. Turner (1775–1851) and John Constable (1776–1837) were fascinated by nature, but their interpretations of it contrasted sharply, aptly symbolizing the tremendous emotional range of the Romantic movement. Turner depicted nature’s power and terror; wild storms and sinking ships were favorite subjects. Constable painted gentle Wordsworthian landscapes in which human beings lived peacefully with their environment, the comforting countryside of unspoiled rural England.

Musicians and composers likewise explored the Romantic sensibility. Abandoning well-defined musical structures, the great Romantic composers used a wide range of forms to create profound musical landscapes that evoked powerful emotions. They transformed the small classical orchestra, tripling its size by adding wind instruments, percussion, and more brass and strings. The crashing chords evoking the surge of the masses in Chopin’s “Revolutionary Etude” and the bottomless despair of the funeral march in Beethoven’s Third Symphony — such were the modern orchestra’s musical paintings that plumbed the depths of human feeling.

This range and intensity gave music and musicians much greater prestige and publicity than in the past. Music no longer simply complemented a church service or helped a nobleman digest his dinner. It became a sublime end in itself, most perfectly realizing the endless yearning of the soul. The unbelievable one-in-a-million performer — the great virtuoso who could transport the listener to ecstasy and hysteria — became a cultural hero. People swooned, for example, for Franz Liszt (1811–1886), the greatest pianist of his age, as they scream for rock stars today.

Delacroix, Massacre at Chios, 1824 This moving masterpiece by Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix portrays an Ottoman massacre of ethnic Greeks on the island of Chios during the struggle for national independence in Greece. The Greek revolt won the enthusiastic support of European liberals, nationalists, and Romantics, and this massive oil painting (ca. 13 feet by 11 feet) portrays the Ottomans as cruel and violent oppressors holding back the course of history.

(Musée du Louvre, Paris, France/Bridgeman Images)

The first great Romantic composer is also the most famous today. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) used contrasting themes and tones to produce dramatic conflict and inspiring resolutions. As one contemporary admirer wrote, “Beethoven’s music sets in motion the lever of fear, of awe, of horror, of suffering, and awakens just that infinite longing which is the essence of Romanticism.”10 Beethoven’s range and output were tremendous. At the peak of his fame, he began to lose his hearing. He considered suicide but eventually overcame despair: “I will take fate by the throat; it will not bend me completely to its will.”11 Beethoven continued to pour out immortal music, although his last years were silent, spent in total deafness.