A History of Western Society: Printed Page 684

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 654

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 683

Chapter Chronology

The European Balance of Power

Elite representatives of the Quadruple Alliance (plus a representative of the restored Bourbon monarch of France) — including Tsar Alexander I of Russia, King Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia, Emperor Franz II of Austria, and their foreign ministers — met to fashion the peace at the Congress of Vienna from September 1814 to June 1815. A host of delegates from the smaller European states also attended the conference and offered minor assistance.

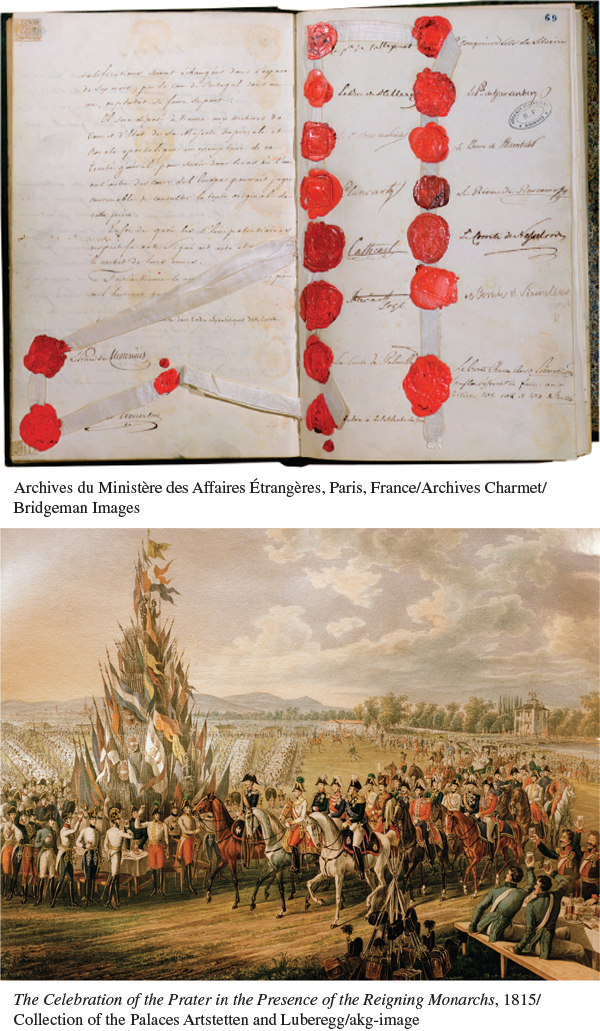

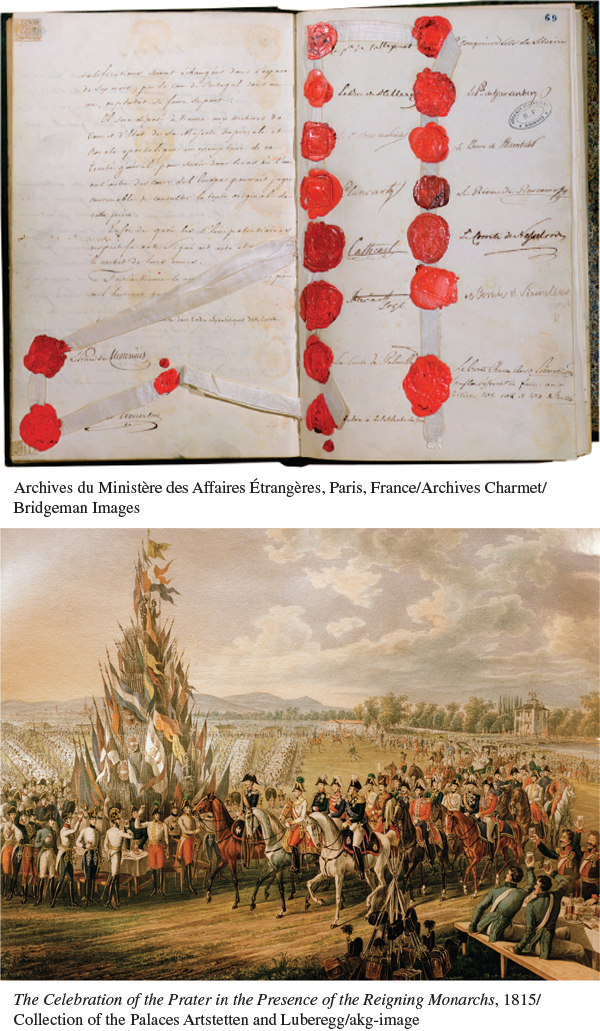

Congress of Vienna The Congress of Vienna was renowned for its intense diplomatic deal making, resulting in the Treaty of Vienna, the last page of which was signed and sealed in 1815 by the representatives of the various European states attending the conference (inset). The congress won additional notoriety for its ostentatious parades, parties, and dance balls. The painting here portrays a mounted group of European royalty, led by the Prussian emperor and the Russian tsar, in a flamboyant parade designed to celebrate Napoleon’s defeat the year before. Onlookers toast the victorious monarchs. The display of flags, weapons, and heraldic emblems symbolizes the unity of Europe’s Great Powers, while the long tables in the background suggest the extent of the festivities. Such images were widely distributed to engender popular support for the conservative program.

painting: The Celebration of the Prater in the Presence of the Reigning Monarchs, 1815/Collection of the Palaces Artstetten and Luberegg/akg-image

Page 685

Such a face-to-face meeting of kings and emperors was very rare at the time. Professional ambassadors and court representatives had typically conducted state-to-state negotiations; now national leaders engaged in what we would today call “summit diplomacy.” Participants at the congress enjoyed any number of festivities associated with aristocratic court culture, including formal receptions, military parades and reviews, sumptuous dinner parties, fancy ballroom dances, fireworks displays, and operatic and theatrical productions. Participation in Vienna’s vibrant salon culture offered further opportunities to socialize, discuss current issues, and make informal deals that could be confirmed at the conference table. All the while, newspapers, pamphlets, periodicals, and satiric cartoons kept readers across Europe up-to-date on social events as well as the latest political developments and agreements. The conference thus marked an important transitional moment in Western history. The salon society and public sphere of the seventeenth-century Enlightenment (see Chapter 16) gradually shifted toward nineteenth-century cultures of publicity and public opinion informed by more modern mass-media campaigns.1

The allied powers were concerned first and foremost with the defeated enemy, France. Self-interest and traditional ideas about the balance of power motivated allied moderation toward the former foe. To Klemens von Metternich (MEH-tuhr-nihk) and Robert Castlereagh (KA-suhl-ray), the foreign ministers of Austria and Great Britain, the balance of power meant an international equilibrium of political and military forces that would discourage aggression by any combination of states or, worse, the domination of Europe by any single state. Their French negotiating partner, the skillful and cynical diplomat Charles Talleyrand, concurred.

The allies offered France lenient terms after Napoleon’s abdication. They agreed to restore the Bourbon king to the French throne. The first Treaty of Paris, signed before the conference (and before Napoleon escaped from Elba and attacked the Bourbon regime), gave France the boundaries it had possessed in 1792, which were larger than those of 1789. In addition, France did not have to pay war reparations. Thus the victorious powers avoided provoking a spirit of victimization and desire for revenge in the defeated country.

The Quadruple Alliance combined leniency with strong defensive measures designed to raise barriers against the possibility of renewed French aggression. Belgium and Holland — incorporated into the French empire under Napoleon — were united under an enlarged and independent “Kingdom of the Netherlands” capable of opposing French expansion to the north. The German-speaking lands on France’s eastern border, also taken by Napoleon (see Chapter 19), were returned to Prussia. As a famous German anthem put it, the expanded Prussia would now stand as the “watch on the Rhine” against French attack. In addition, the allies reorganized the German-speaking territories of central Europe. A new German Confederation, a loose association of German-speaking states based on Napoleon’s reorganization of the territory dominated by Prussia and Austria, replaced the roughly three hundred principalities, free cities, and dynastic states of the Holy Roman Empire with just thirty-eight German states (see Map 21.1).

Page 686

Page 687

Austria, Britain, Prussia, and Russia furthermore used the balance of power to settle their own potentially dangerous disputes. The victors generally agreed that each of them should receive compensation in the form of territory for their victory over the French. Great Britain had already won colonies and strategic outposts during the long wars. Austria gave up territories in Belgium and southern Germany but expanded greatly elsewhere, taking the rich provinces of Venetia and Lombardy in northern Italy as well as former Polish possessions and new lands on the eastern coast of the Adriatic.

Russian and Prussian claims for territorial expansion were more contentious. When Russia had pushed Napoleon out of central Europe, its armies had expanded its control over Polish territories. Tsar Alexander I wished to make Russian rule permanent. But when France, Austria, and Great Britain all argued for limits on Russian gains, the tsar ceded territories back to Prussia and accepted a smaller Polish kingdom. Prussian claims on the state of Saxony, a wealthy kingdom in the German Confederation, were particularly contentious. The Saxon king had supported Napoleon to the bitter end; now Wilhelm III wanted to incorporate Saxony into Prussia. Under pressure, he agreed to partition the state, leaving an independent Saxony in place, a change that posed no real threat to its Great Power neighbors but soothed their fears of Prussian expansionism. These territorial changes and compromises fell very much within the framework of balance-of-power ideology.

Unfortunately for France, in February 1815 Napoleon suddenly escaped from his “comic kingdom” on the island of Elba and re-ignited his wars of expansion for a brief time (see Chapter 19). Yet the second Treaty of Paris, concluded in November 1815 after Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo, was still relatively moderate toward France. The elderly Louis XVIII was restored to his throne for a second time. France lost only a little territory, had to pay an indemnity of 700 million francs, and was required to support a large army of occupation for five years. The rest of the settlement concluded at the Congress of Vienna was left intact. The members of the Quadruple Alliance, however, did agree to meet periodically to discuss their common interests and to consider appropriate measures for the maintenance of peace in Europe. This agreement marked the beginning of the European “Congress System,” which lasted long into the nineteenth century and settled many international crises peacefully, through international conferences or “congresses” and balance-of-power diplomacy.