A History of Western Society: Printed Page 725

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 693

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 723

Chapter Chronology

Improvements in Urban Planning

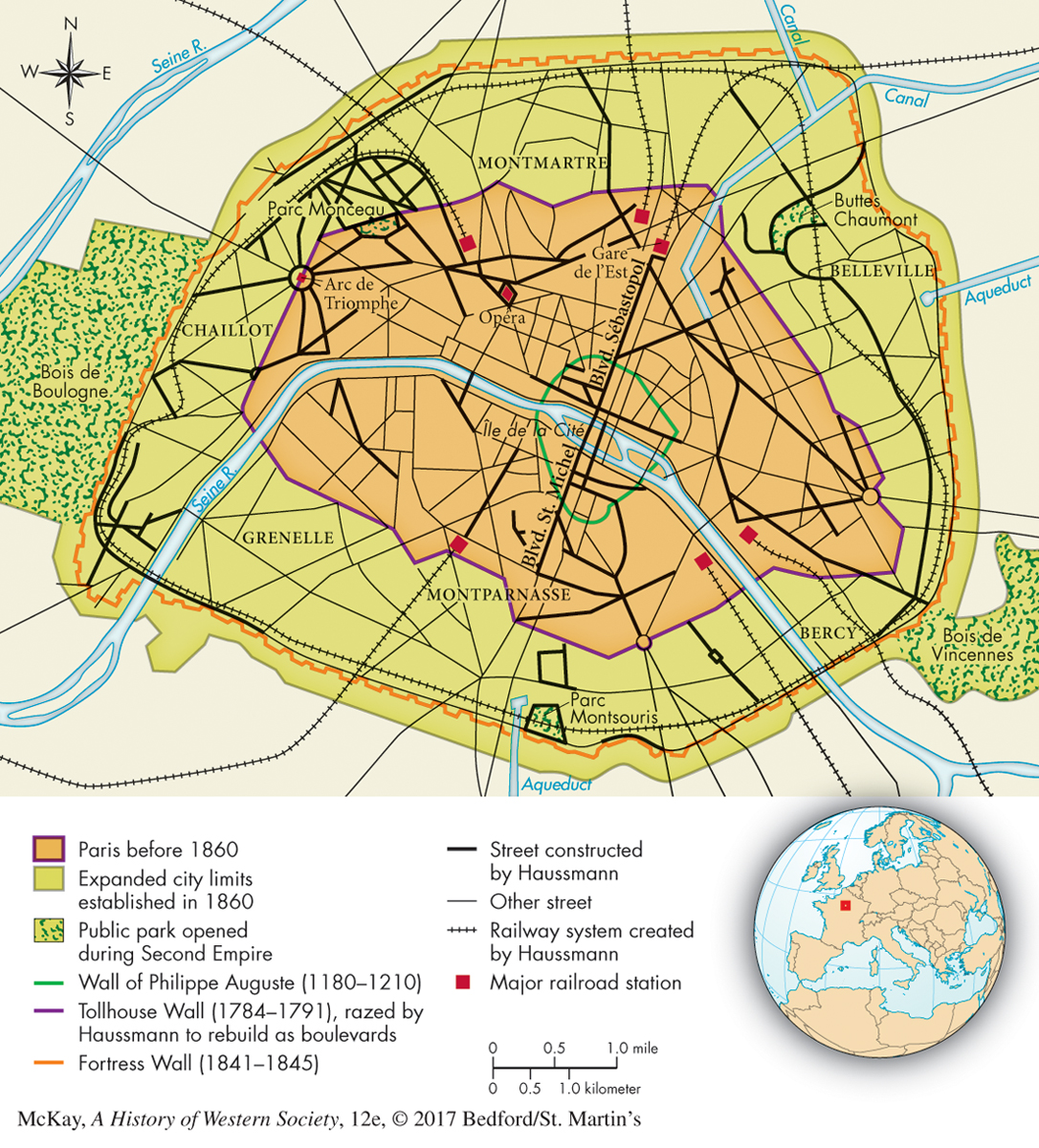

In addition to public health improvements, more effective urban planning was an important key to unlocking a better quality of urban life in the nineteenth century. France took the lead in this area during the rule of Napoleon III (r. 1848–1870), who used government action to promote the welfare of his subjects. Napoleon III believed that rebuilding much of Paris would provide employment, improve living conditions, limit the outbreak of cholera epidemics — and testify to the power and glory of his empire. He hired Baron Georges Haussmann (HOWS-muhn) (1809–1884), an aggressive, impatient Alsatian, to modernize the city. An authoritarian manager and capable city planner, Haussmann bulldozed both buildings and opposition. In twenty years Paris was completely transformed (Map 22.2).

Figure 22.3: MAP 22.2 The Modernization of Paris, ca. 1850–1870 The addition of broad boulevards, large parks, and grand train stations transformed Paris. The cutting of the new north-south axis — known as the Boulevard Saint-Michel — was one of Haussmann’s most controversial projects. His plan razed much of Paris’s medieval core and filled the Île de la Cité with massive government buildings. Note the addition of new streets and light rail systems (the basis of the current Parisian subway system, the “metro”) that encircle the city core, emblematic of the public transportation revolution that enhanced living conditions in nineteenth-century European cities.

The Paris of 1850 was a labyrinth of narrow, dark streets, the results of desperate overcrowding and a lack of effective planning. More than one-third of the city’s 1 million inhabitants lived in a central district not twice the size of New York’s Central Park. Residents faced terrible conditions and extremely high death rates. The entire metropolis had few open spaces and only two public parks.

For two decades Haussmann and his fellow planners proceeded on many interrelated fronts. With a bold energy that often shocked their contemporaries, they razed old buildings in order to cut broad, straight, tree-lined boulevards through the center of the city as well as in new quarters rising on the outskirts (see Map 22.2). These boulevards, designed in part to prevent the easy construction and defense of barricades by revolutionary crowds, permitted traffic to flow freely and afforded impressive vistas. Their creation demolished some of the worst slums. New streets stimulated the construction of better housing, especially for the middle classes. Planners created small neighborhood parks and open spaces throughout the city and developed two very large parks suitable for all kinds of holiday activities — one on the affluent west side and one on the poor east side of the city. The city improved its sewers, and a system of aqueducts more than doubled the city’s supply of clean, fresh water.

Page 726

Rebuilding Paris provided a new model for urban planning and stimulated urban reform throughout Europe, particularly after 1870. In city after city, public authorities mounted a coordinated attack on many of the interrelated problems of the urban environment. As in Paris, improvements in public health through better water supply and waste disposal often went hand in hand with new boulevard construction. Urban planners in cities such as Vienna and Cologne followed the Parisian example of tearing down old walled fortifications and replacing them with broad, circular boulevards on which they erected office buildings, town halls, theaters, opera houses, and museums. These ring roads and the new boulevards that radiated outward from the city center eased movement and encouraged urban expansion (see Map 22.2). Zoning expropriation laws, which allowed a majority of the owners of land in a given quarter of the city to impose major street or sanitation improvements on a reluctant minority, were an important mechanism of the urban reform movement.

Urban Poverty Nineteenth-century London was notorious for its urban squalor, captured in this 1895 photo of Kensington High Street. For the families that lived in these ramshackle apartments, this small, unsanitary courtyard served as a cramped recreation, market, and working space.

(Market Court, Kensington High Street, London, c. 1895/English Heritage/Heritage Images/Getty Images)