A History of Western Society: Printed Page 732

Chapter Chronology

Living in the Past

Nineteenth-Century Women’s Fashion

Page 732

I n the last third of the nineteenth century, fashionable clothing, especially for middle-class women, became the first modern consumer industry, as shoppers snapped up the constantly changing ready-to-wear goods sold by large department stores. Before the twentieth century, when society fragmented into many different groups expressing themselves in many clothing styles, clothing patterns focused mainly on perceived differences in class and gender. Most changes in women’s fashion originated in Paris in the nineteenth century. The crinoline dresses from 1869 shown on this page were worn exclusively by aristocratic and wealthy middle-class women, initially in France, and then across the Western world. These expensive dresses, flawlessly tailored by skilled seamstresses, abounded in elaborate embroidery, rich velvety materials, and fancy accessories. The circular spread of the gowns was created by the crinoline, a slip with a metal hoop that held the skirt out on all sides. Underneath their dress, women wore a corset, the century’s most characteristic women’s undergarment, which was laced up tightly in back and which pressed unmercifully inward from the breasts to the hips.

Crinoline dresses, Paris, 1869.

(Private Collection/Bridgeman Images)

By 1875, as shown in this painting of a middle-class interior (below), the corset still bound a woman’s frame, but the crinoline hoop had been replaced by the bustle, a cotton fan with steel reinforcement that pushed the dress out in back to exaggerate gender differences. Worn initially by the wealthy elite, the bustle became the standard for middle-class women when cheaper ready-to-wear versions became available throughout Europe in department stores or mail-order catalogues. Emulating the elite in style, conventional middle-class women shopped carefully, scouting for sales. They used fashion to distinguish themselves from working-class women, who wore simple cotton clothes, just as the wealthy had tried to use clothing to differentiate themselves from the middle class earlier in the century.

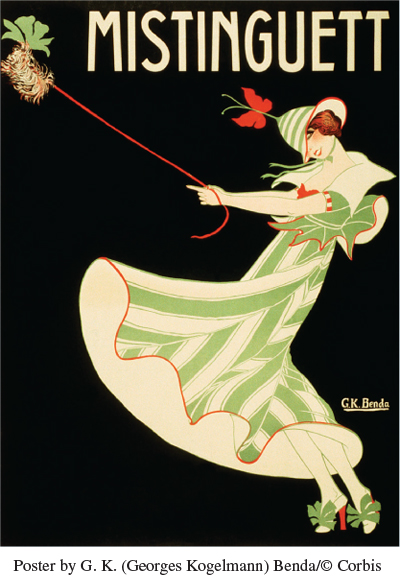

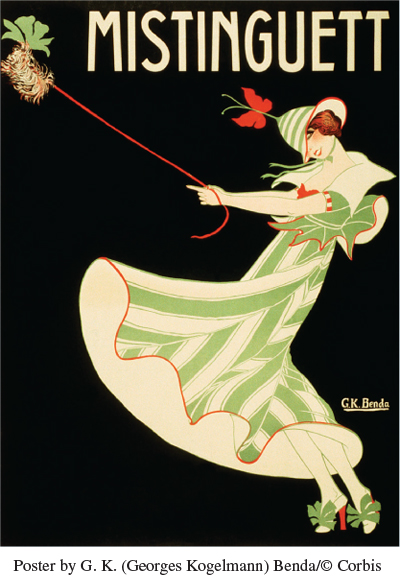

By century’s end alternative styles of dress had emerged. The young middle-class Englishwoman in this 1893 photo (below) has chosen a woman’s tailored suit, the only major English innovation in nineteenth-century women’s fashion. This alternative dress combined the tie, suit jacket, vest, and straw hat of male attire with typical feminine elements, such as the skirt and gloves. This practical, socially accepted dress appealed to the growing number of women in paid employment in the 1890s. By the early part of the twentieth century, the corset had given way entirely to the more flexible brassiere and the mainstream embrace of loose-fitting garments, as illustrated by this 1910 French advertisement (below).

Page 733

Summer dress with bustle, England, 1875.

(Roy Miles Fine Paintings/Bridgeman Images)

Alternative dress, England, 1893.

(Manchester Art Gallery, UK/Bridgeman Images)

Loose-fitting dress, France, 1910.

(Poster by G. K. [Georges Kogelmann] Benda/© Corbis)

- What does the image from 1869 tell you about the life of these women (their work, leisure activities, and so on)? What implications, if any, do you think the later styles shown here had for women’s lives? For class distinctions?

- What does the impractical, restrictive clothing in these images reveal about society’s view of women during this period? What is the significance of the emergence of loose-fitting or other alternative styles of dress?

- Historian Diana Crane has argued that women’s departure from a dominant style can be seen as a symbolic, nonverbal assertion of independence and equality with men. Do you agree? Did the greater freedom of movement in clothing in the twentieth century reflect the emerging emancipation of Western women? Or was the coquettish femininity of loose, flowing dresses only a repackaging of the dominant culture’s sharply defined gender boundaries?