A History of Western Society: Printed Page 746

Thinking Like a Historian

The Promise of Electricity

The commercialization and widespread use of electricity around 1900 made possible a broad spectrum of new technologies in the late nineteenth century, including telephones and telegraphs; radio; electric lights in public and private space; electric railroads, trams, and subways; electrochemistry and electrometallurgy; power plants, generators, and batteries; and electric motors and machines. How did the arrival of electricity change people’s lives?

| 1 |

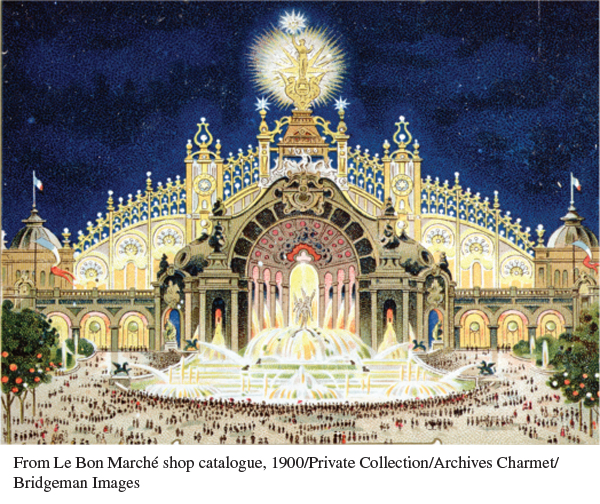

The Palace of Electricity, 1900 Universal Exhibition, Paris. The ever- |

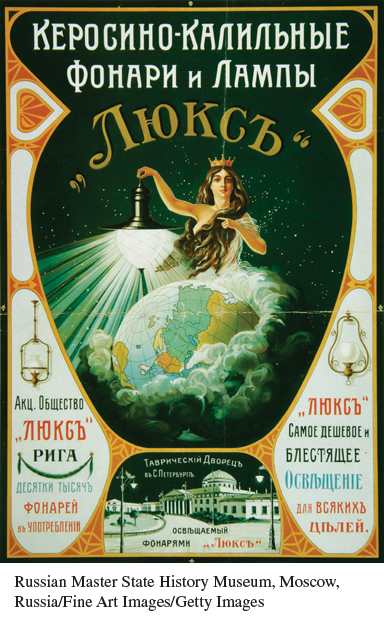

| 2 | “Luks’ — The Least Expensive and Brightest Lighting for All Occasions,” ca. 1900. This Russian poster advertising lighting systems from the Luks’ (Deluxe) lighting company in Riga promotes “kerosene and incandescent lights and bulbs” and so marks a transitional period, when lighting companies encouraged consumers to switch from gas to electricity. The poster portrays a princess of light, holding an electric bulb that illuminates first the Russian Empire and then the rest of the globe. The small scene at the bottom shows the historic Tauride Palace in St. Petersburg and suggests the revolutionary effect of electric light in public spaces. |

| 3 | “Electrical Progress in Great Britain During 1909.” An American journal for electricians offered glowing approval of the electrification of Great Britain. Along with the United States, Britain was a world leader in electrification around 1900; other European nations were not far behind. |

![]() The most noticeable and at the same time the most hopeful, feature of the year 1909 in the United Kingdom, has been the great progress made in bringing electricity within the compass of the “small man.” This movement, which means so much for the future of all electrical industry, has occupied the close attention of a large proportion of the electricity works managers and engineers and of most manufacturing and importing businesses. . . .

The most noticeable and at the same time the most hopeful, feature of the year 1909 in the United Kingdom, has been the great progress made in bringing electricity within the compass of the “small man.” This movement, which means so much for the future of all electrical industry, has occupied the close attention of a large proportion of the electricity works managers and engineers and of most manufacturing and importing businesses. . . .

[T]he forward movement [of the filament lamp] is now in full swing. The wire lamp is everywhere working wonders in reducing the cost of electric lighting on existing installations and that fact together with the very strong support that is being given by other influences, is making it easier to get electrical applications adopted in many places where it seemed impossible before. . . .

[The London power companies] are now jointly using the daily press in an advertising campaign so conducted as to command the attention of all who read, educating them as to the rightful claims of electricity. One of the companies has opened a model “Electric Home” in its area, fitted throughout with electric lighting, heating, and small power. The house is occupied by a tenant who is under special arrangement to admit the public between certain hours every day, to demonstrate to them the manifold domestic applications of electricity and their convenience and cleanliness. Neither coal nor gas is used for any purpose whatsoever in the house. . . .

[The report then describes a number of technological advances, including newly built electric-

| 4 |

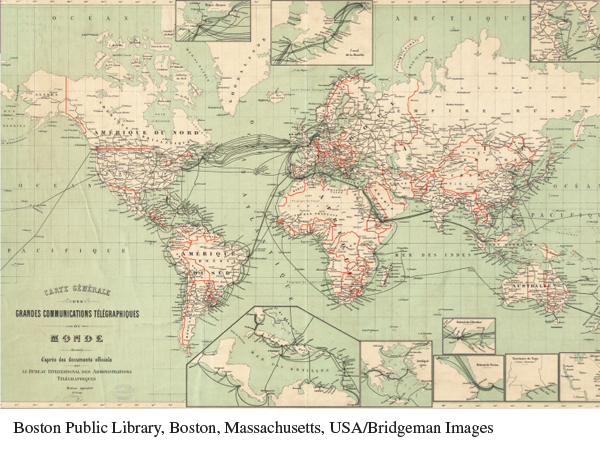

“General Map of Large- |

| 5 | Electric trams and lines in Piazza del Duomo, Milan, Italy, ca. 1900. Electric streetcar and subway systems made quick travel through urban spaces accessible and inexpensive. In Milan, the tracks and streetcars, and the installation of electric streetlights, strike a modern contrast to the Gothic cathedral and Neoclassical triumphal arch that frame the central square. |

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

- How did the commercialization of electricity reflect and/or contribute to the late-

nineteenth- century faith in progress, rationalism, and reform? - What sort of research and development model did it take to electrify Europe? What sort of business model? How were the two connected?

- Even in 1900, it was hard to predict that electricity would be more popular than gas or coal as a source for energy use at home or in the workplace. In Sources 1, 2, and 3, how do electricity’s boosters strive to popularize the residential and commercial use of electricity?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Using the sources above, along with what you have learned in class, in Chapter 22, and in the sections on the Industrial Revolution in Chapter 17, write a short essay that describes the effects of electrification on European society. Was electricity a fundamental driving force in the history of Western society?

Sources: (3) Albert H. Bridge, “Electrical Progress in Great Britain in 1909,” Electrical Review and Western Electrician, January 1, 1910, 17–19.