A History of Western Society: Printed Page 776

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 746

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 776

Chapter Chronology

Great Britain and Ireland

Historians often cast late-nineteenth-century Britain as a shining example of peaceful and successful political evolution, where an effective two-party Parliament skillfully guided the country from classical liberalism to full-fledged democracy with hardly a misstep. This “Whig view” of Great Britain is not so much wrong as it is incomplete. After the right to vote was granted to males of the wealthy middle class in 1832, opinion leaders and politicians wrestled for some time with further expansion of the franchise. In 1867 the Second Reform Bill of Benjamin Disraeli and the Conservative Party extended the vote to all middle-class males and the best-paid workers in order to broaden their own base of support beyond the landowning class. After 1867 English political parties and electoral campaigns became more modern, and the “lower orders” appeared to vote as responsibly as their “betters.” Hence the Third Reform Bill of 1884 gave the vote to almost every adult male.

While the House of Commons drifted toward democracy, the House of Lords was content to slumber nobly. Between 1901 and 1910, however, the Lords tried to reassert itself. Acting as supreme court of the land, it ruled against labor unions in two important decisions. And after the Liberal Party came to power in 1906, the Lords vetoed several measures passed by the Commons, including the so-called People’s Budget, designed to increase spending on social welfare services. When the king threatened to create enough new peers to pass the bill, the Lords finally capitulated, as they had with the Reform Bill of 1832 (see Chapter 21). Aristocratic conservatism yielded to popular democracy.

Extensive social welfare measures, previously slow to come to Great Britain, were passed in a spectacular rush between 1906 and 1914. During those years the Liberal Party, inspired by the fiery Welshman David Lloyd George (1863–1945), enacted the People’s Budget and substantially raised taxes on the rich. This income helped the government pay for national health insurance, unemployment benefits, old-age pensions, and a host of other social measures. The state tried to integrate the urban masses socially as well as politically, though the refusal to grant women the right to vote encouraged a determined and increasingly militant suffrage movement (see Chapter 22).

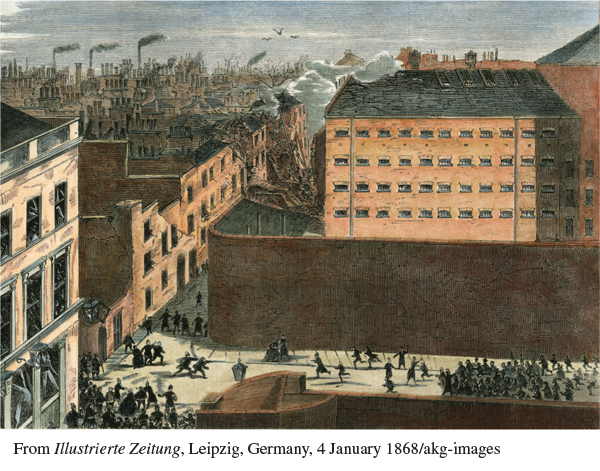

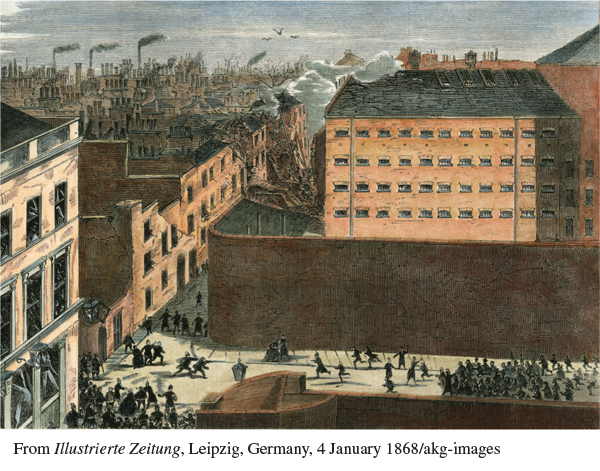

This record of accomplishment was only part of the story, however. On the eve of World War I, the unanswered question of Ireland brought Great Britain to the brink of civil war. The terrible Irish famine of the 1840s and early 1850s had fueled an Irish revolutionary movement. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, established in 1858 and known as the “Fenians,” engaged in violent campaigns against British rule. The British responded with repression and arrests (see image below). Seeking a way out of the conflict, the English slowly granted concessions, such as rights for Irish peasants and the abolition of the privileges of the Anglican Church. Liberal prime minister William Gladstone (1809–1898), who twenty years earlier had proclaimed, “My mission is to pacify Ireland,” introduced bills to give Ireland self-government, or home rule, in 1886 and in 1893. They failed to pass, but in 1913 Irish nationalists finally gained such a bill for Ireland.

Irish Home Rule In December 1867 members of the “Fenians,” an underground group dedicated to Irish independence from British rule, detonated a bomb outside Clerkenwell Prison in London. Their attempt to liberate Irish Republican activists failed. Though the bomb blew a hole in the prison walls, damaged nearby buildings, and killed twelve innocent bystanders, no Fenians were freed. The British labeled the event the “Clerkenwell Outrage,” and its violence evokes revealing parallels with the radical terrorist attacks of today.

(From Illustrierte Zeitung, Leipzig, Germany, 4 January 1868/akg-images)

Page 777

Thus Ireland, the Emerald Isle, was on the brink of achieving self-government. Yet to the same extent that the Catholic majority in the southern counties wanted home rule, the Protestants of the northern counties of Ulster came to oppose it. Motivated by the accumulated fears and hostilities of generations, the Ulster Protestants refused to submerge themselves in a majority-Catholic Ireland, just as Irish Catholics had refused to submit to a Protestant Britain.

The Ulsterites vowed to resist home rule. By December 1913 they had raised one hundred thousand armed volunteers, and much of English public opinion supported their cause. In response, in 1914 the Liberals in the House of Lords introduced a compromise home-rule bill that did not apply to the northern counties. This bill, which openly betrayed promises made to Irish nationalists, was rejected in the Commons, and in September the original home-rule bill passed but with its implementation delayed. The Irish question had been overtaken by the earth-shattering world war that began in August 1914, and final resolution was suspended for the duration of the hostilities.

Irish developments illustrated once again the power of national feeling and national movements in the nineteenth century. Moreover, they demonstrated that central governments could not elicit greater loyalty unless they could capture and control that elemental current of national feeling. Though Great Britain had much going for it — power, parliamentary rule, prosperity — none of these availed in the face of the conflicting nationalisms created by Irish Catholics and Protestants. Similarly, progressive Sweden was powerless to stop a Norwegian national movement, which culminated in Norway’s leaving Sweden and becoming fully independent in 1905. In this light, one can also understand the difficulties faced by the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans in the late nineteenth century. It was only a matter of time before the Serbs, Bulgarians, and Romanians would break away.