A History of Western Society: Printed Page 780

Thinking Like a Historian

How to Build a Nation

Nationalism permeated many aspects of everyday life and became a powerful political ideology in the late nineteenth century. Yet Europeans were divided by opposing regional and religious loyalties, social and class divisions, and ethnic differences, so developing a sense of national belonging among ordinary people posed a problem. How did leaders encourage citizens to embrace national identities?

| 1 | Ernest Renan, “What Is a Nation?” 1882. In a famous lecture, French philosopher Ernest Renan argued that national identity depended on an imagined past that had less to do with historical reality than with contemporary aspirations for collective belonging. |

![]() A nation is a soul, a spiritual principle. Two things, which in truth are but one, constitute this soul or spiritual principle. One lies in the past, one in the present. One is the possession in common of a rich legacy of memories; the other is present-

A nation is a soul, a spiritual principle. Two things, which in truth are but one, constitute this soul or spiritual principle. One lies in the past, one in the present. One is the possession in common of a rich legacy of memories; the other is present-

More valuable by far than common customs posts and frontiers conforming to strategic ideas is the fact of sharing, in the past, a glorious heritage and regrets, and of having, in the future, [a shared] programme to put into effect, or the fact of having suffered, enjoyed, and hoped together. These are the kinds of things that can be understood in spite of differences of race and language. I spoke just now of “having suffered together” and, indeed, suffering in common unifies more than joy does. Where national memories are concerned, griefs are of more value than triumphs, for they impose duties, and require a common effort.

A nation is therefore a large-

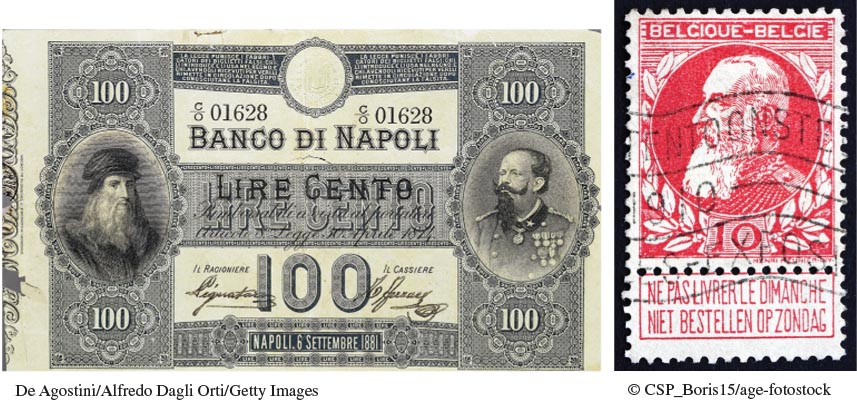

| 2 | National banknotes and stamps. Patriotic images turned up in everyday places. An Italian banknote (1881), for example, featured Leonardo da Vinci and King Victor Emmanuel II, while a Belgian stamp (1905) portrayed King Leopold II. |

| 3 |

“The Watch on the Rhine,” lyrics 1840, music 1854. German soldiers sang this triumphal patriotic anthem about the Rhine River, which defines the borderlands between France and Germany, as they marched to fight in the Franco- |

![]()

A voice resounds like thunder-

’Mid dashing waves and clang of steel:

The Rhine, the Rhine, the German Rhine!

Who guards to-

[Chorus] Dear Fatherland, no danger thine;

Firm stand thy sons to watch the Rhine!

They stand, a hundred thousand strong,

Quick to avenge their country’s wrong;

With filial love their bosoms swell,

They’ll guard the sacred landmark well!

Chorus

The dead of an heroic race

From heaven look down and meet this gaze;

He swears with dauntless heart, “O Rhine,

Be German as this breast of mine!”

Chorus

While flows one drop of German blood,

Or sword remains to guard thy flood,

While rifle rests in patriot hand,

No foe shall tread thy sacred strand!

Chorus

Our oath resounds, the river flows,

In golden light our banner glows;

Our hearts will guard thy stream divine:

The Rhine, the Rhine, the German Rhine!

Chorus

| 4 | Monument to the Battle of Nations, Leipzig, Germany, 1913. This colossal monument commemorates the victory of the Prussians and their allies over Napoleon in 1813. A large statue of the archangel Michael underneath an inscription reading “Gott Mit Uns” (God with Us) guards the entrance, while Teutonic knights with drawn swords stand watch around the memorial’s crest. The visitors climbing the stairs at the bottom left of the photo give some idea of the monument’s size. |

| 5 |

The National Monument to King Victor Emmanuel II, Rome, Italy, 1911. Nicknamed the “wedding cake” by local wits, this memorial/museum features an equestrian statue of the king above a frieze representing the Italian people, and an imposing Roman- |

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

- In Source 1, why does Ernest Renan conclude that “[a] nation’s existence is . . . a daily plebiscite”?

- Consider Sources 2–5. What symbols or ideas are used to promote a sense of national belonging? Why, for example, would an Italian banknote feature an image of the sixteenth-

century artist/philosopher Leonardo da Vinci? Why do these sources repeatedly evoke blood, battles, and national leaders? - Are nationalists good historians? Do the sources above accurately represent the “true-

to- life” historic experiences of specific national peoples?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

Using the sources above, along with what you have learned about nationalism in class and in Chapters 21 and 23, write a short essay that applies Ernest Renan’s ideas about national identity to the spread of nationalism in the late nineteenth century. Can you explain why nationalism might subsume or erode existing regional, religious, or class differences?

Sources: (1) Ernest Renan, “What Is a Nation?” trans. Martin Thom, in Nation and Narration, ed. Homi K. Bhabha (New York: Routledge, 2003), pp. 19–20; (3) Eva March Tappan, ed., The World’s Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, vol. 7, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), pp. 249–250.