A History of Western Society: Printed Page 783

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 754

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 783

The Socialist International

The growth of socialist parties after 1871 was phenomenal. (See “Evaluating the Evidence 23.3: Adelheid Popp, the Making of a Socialist.”) Neither Bismarck’s Anti-

As the name of the French party suggests, Marxist socialist parties strove to join together in an international organization, and in 1864 Marx himself helped found the socialist International Working Men’s Association, also known as the First International. In the following years, Marx battled successfully to control the organization and used its annual international meetings as a means of spreading his doctrines of socialist revolution. He enthusiastically endorsed the radical patriotism of the Paris Commune and its terrible struggle against the French state as a giant step toward socialist revolution. Marx’s fervent embrace of working-

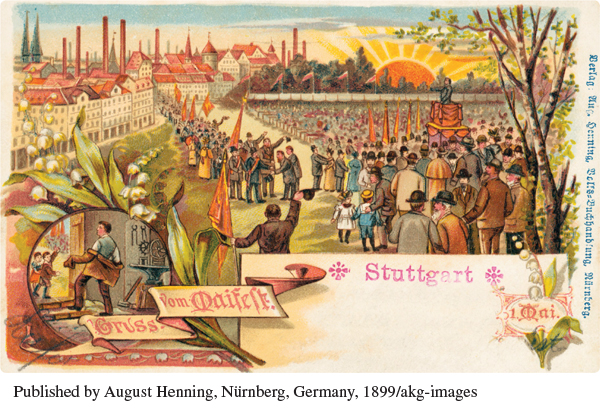

Yet international proletarian solidarity remained an important objective for Marxists. In 1889, as the individual parties in different countries grew stronger, socialist leaders came together to form the Second International, which lasted until 1914. Though only a federation of national socialist parties, the Second International had a great psychological impact. It had a permanent executive, and every three years delegates from the different parties met to interpret Marxist doctrines and plan coordinated action. May 1 (May Day) was declared an annual international one-