A History of Western Society: Printed Page 812

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 781

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 813

Chapter Chronology

A “Civilizing Mission”

Western society did not rest the case for empire solely on naked conquest and a Darwinian racial struggle or on power politics and the need for naval bases on every ocean. Imperialists developed additional arguments for imperialism to satisfy their consciences and answer their critics.

A favorite idea was that Westerners could and should civilize more primitive nonwhite peoples. According to this view, Westerners shouldered the responsibility for governing and converting the supposed savages under their charge and strove to remake them on superior European models. Africans and Asians would eventually receive the benefits of industrialization and urbanization, Western education, Christianity, advanced medicine, and finally higher standards of living. In time, they might be ready for self-government and Western democracy. Thus the French repeatedly spoke of their imperial endeavors as a sacred “civilizing mission.” Other imperialists agreed; as one German missionary put it, a combination of prayer and hard work under German direction would lead “the work-shy native to work of his own free will” and thus lead him to “an existence fit for human beings.”9 Another argument was that imperial government protected natives from tribal warfare as well as from cruder forms of exploitation by white settlers and business people. In 1899 Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936), who wrote masterfully of Anglo-Indian life and was perhaps the most influential British writer of the 1890s, summarized such ideas in his poem “The White Man’s Burden.” (See “Evaluating the Evidence 24.2: The White Man’s Burden.”)

Many Americans accepted the ideology of the white man’s burden. It was an important factor in the decision to rule, rather than liberate, the Philippines after the Spanish-American War. Like their European counterparts, these Americans believed that their civilization had reached unprecedented heights and that they had unique benefits to bestow on supposedly less advanced peoples.

Though the colonial administrators and military generals in charge of imperial endeavors were men, European women played a central role in the “civilizing mission.” Proponents of imperial expansion actively encouraged women to “serve” in the colonies, and many answered the call. Some women worked as colonial missionaries, teachers, and nurses; others accompanied their husbands overseas. Europeans who embraced the “white man’s burden” believed that the presence of white women in the colonies might help stop the spread of what they called “race mixing”: the tendency of European men to establish cross-race marriages or relationships with indigenous women. If they stayed in the colonies long enough to establish a semipermanent household, European women might oversee native servants. Colonial encounters thus established complicated social hierarchies that entangled race, class, and gender. (See “Thinking Like a Historian: Women and Empire.”)

Peace and stability under European control also facilitated the spread of Christianity. Catholic and Protestant missionaries — both men and women — competed with Islam south of the Sahara, seeking converts and building schools to spread the Gospel. Many Africans’ first real contact with whites was in mission schools. Some peoples, such as the Ibo in Nigeria, became highly Christianized.

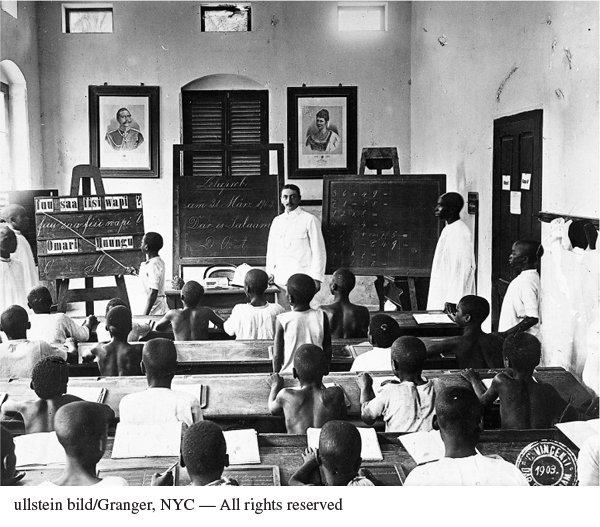

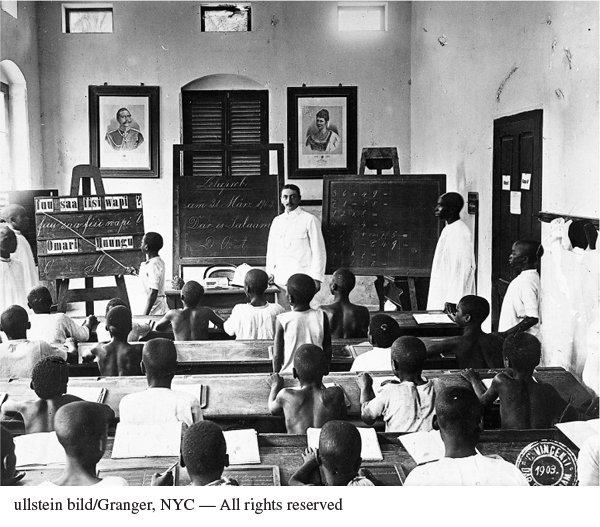

A Missionary School A Swahili schoolboy leads his classmates in a reading lesson in Dar es Salaam in German East Africa in 1903; portraits of Emperor Wilhelm II and his wife look down on the classroom, a reminder of imperial control. Europeans argued that they were spreading the benefits of a superior civilization with schools like this one, which is unusually well built and furnished because of its strategic location in the capital city. Schoolrooms were typically segregated by sex, and lessons for young men and women adhered to Western notions of gender difference.

(ullstein bild/Granger, NYC — All rights reserved)

Such occasional successes in sub-Saharan Africa contrasted with the general failure of missionary efforts in India, China, and the Islamic world. There Christians often preached in vain to peoples with ancient, complex religious beliefs. Yet the number of Christian believers around the world did increase substantially in the nineteenth century, and missionary groups kept trying.