A History of Western Society: Printed Page 813

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 783

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 815

Chapter Chronology

Orientalism

Even though many Westerners shared a sense of superiority over non-Western peoples, they were often fascinated by foreign cultures and societies. In the late 1970s the influential literary scholar Edward Said (sigh-EED) (1935–2003) coined the term Orientalism to describe this fascination and the stereotypical and often racist Western understandings of non-Westerners that dominated nineteenth-century Western thought. Said originally used “Orientalism” to refer to the way Europeans viewed “the Orient,” or Arab societies in North Africa and the Middle East. The term caught on, however, and is often used more broadly to refer to Western views of non-Western peoples across the globe.

Said believed that it was almost impossible for people in the West to look at or understand non-Westerners without falling into some sort of Orientalist stereotype. Politicians, scholarly experts, writers and artists, and ordinary people readily adopted “us versus them” views of foreign peoples. The West, they believed, was modern, while the non-West was primitive. The West was white, the non-West colored; the West was rational, the non-West emotional; the West was Christian, the non-West pagan or Islamic. As part of this view of the non-West as radically “other,” Westerners imagined the Orient as a place of mystery and romance, populated with exotic, dark-skinned peoples, where Westerners might have remarkable experiences of foreign societies and cultures.

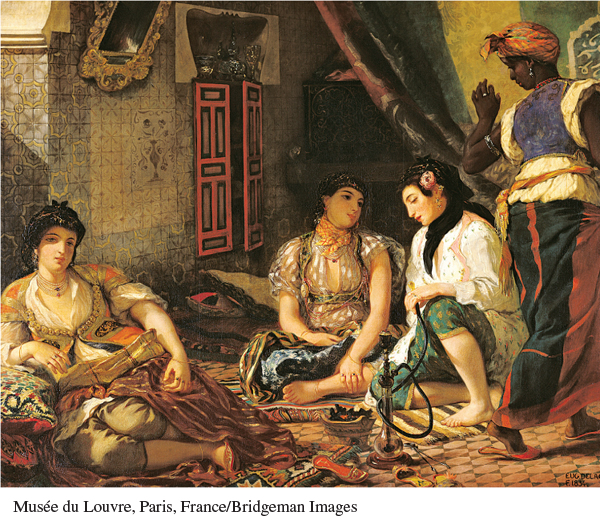

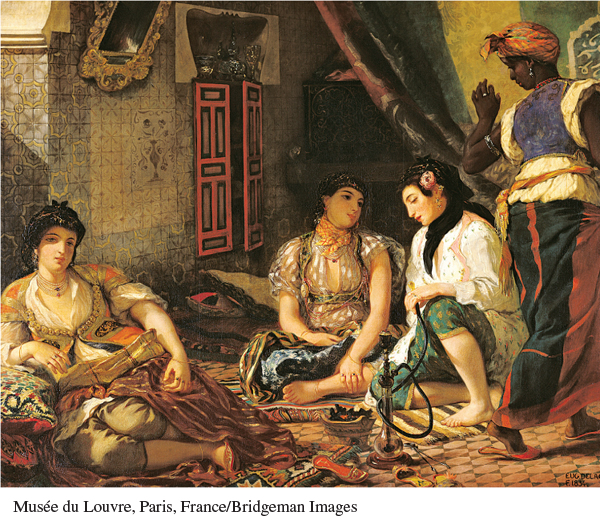

Orientalism in Western Society Stereotyped Western impressions of Arabs and the Islamic world became increasingly popular in the West in the nineteenth century. This wave of Orientalism found expression in high art, as in the renowned painting Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1834), by the French painter Eugène Delacroix (left). Delacroix portrays three women and their African servant at rest in a harem, the segregated, women-only living quarters for the wives of elite Muslim men (Islamic law allows a man to have several wives). Orientalist ideas also made their way into the fabric of everyday life, when ordinary people visited museum exhibits, read newspaper articles, or purchased popular colonial products like cigarettes, coffee, and chocolate.

(Musée du Louvre, Paris, France/Bridgeman Images)

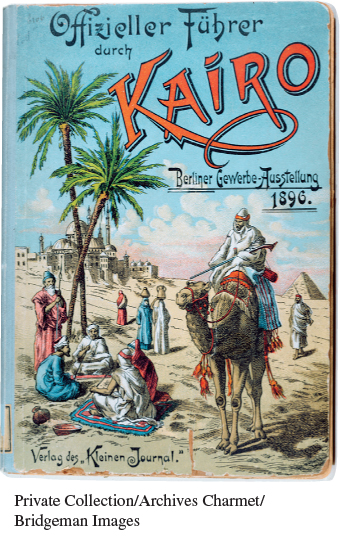

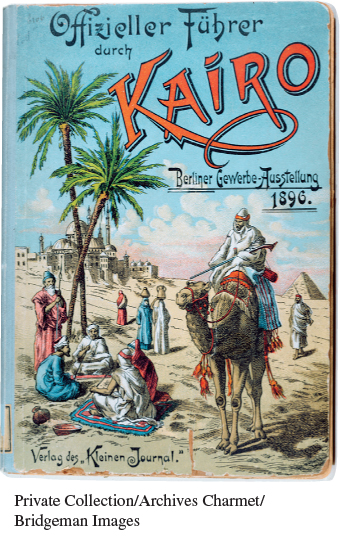

Travel Guide This “Official Guide” (above) to an exhibition on Cairo held in Berlin offered an exotic look at foreign lands. Note the veiled women in the center and the pyramid and desert mosque in the background.

(Private Collection/Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images)

Page 816

Such views swept through North American and European scholarship, arts, and literature in the late nineteenth century. The emergence of ethnography and anthropology as academic disciplines in the 1880s was part of the process. Inspired by a new culture of collecting, scholars and adventurers went into the field, where they studied supposedly primitive cultures and traded for, bought, or stole artifacts from non-Western peoples. The results of their work were reported in scientific studies, articles, and books, and intriguing objects filled the display cases of new public museums of ethnography and natural history. In a slew of novels published around 1900, authors portrayed romance and high adventure in the colonies and so contributed to the Orientalist worldview. Artists followed suit, and dramatic paintings of ferocious Arab warriors, Eastern slave markets, and the sultan’s harem adorned museum walls and wealthy middle-class parlors. Scholars, authors, and artists were not necessarily racists or imperialists, but they found it difficult to escape Orientalist stereotypes. In the end they helped spread the notions of Western superiority and justified colonial expansion.