A History of Western Society: Printed Page 875

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 841

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 876

Chapter Chronology

New Artistic Movements

In the decades surrounding the First World War, the visual arts also experienced radical change and experimentation. For the last several centuries, artists had tried to produce accurate representations of reality. Now a new artistic avant-garde emerged to challenge that practice. From Impressionism and Expressionism to Dadaism and Surrealism, a sometimes-bewildering array of artistic movements followed one after another. Modern painting and sculpture became increasingly abstract as artists turned their backs on figurative representation and began to break down form into its constituent parts: lines, shapes, and colors.

Berlin, Munich, Moscow, Vienna, New York, and especially Paris became famous for their radical artistic undergrounds. Commercial art galleries and exhibition halls promoted the new work, and schools and institutions, such as the Bauhaus, emerged to train a generation in modern techniques. Young artists flocked to these cultural centers to participate in the new movements, earn a living making art, and perhaps change the world with their revolutionary ideas.

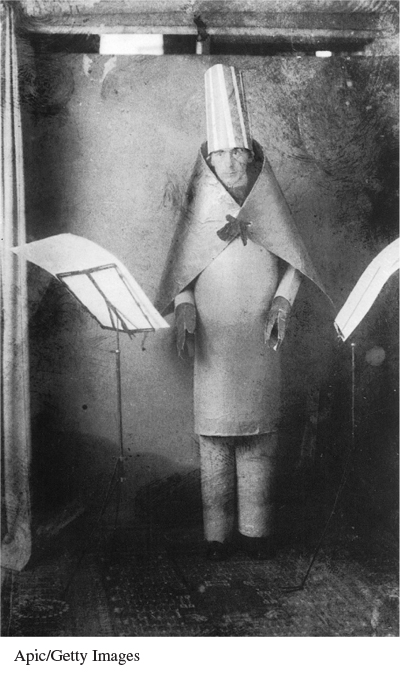

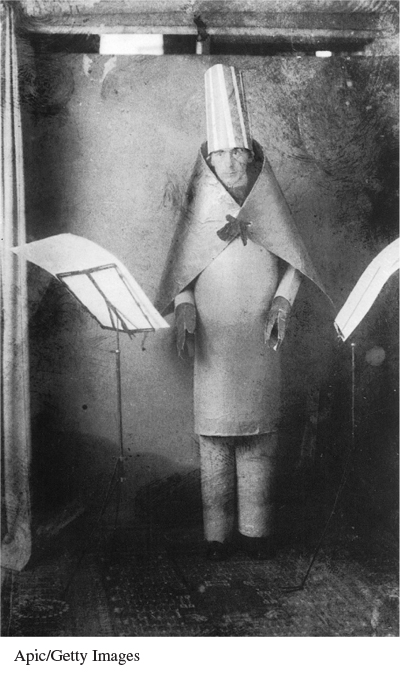

The Shock of the Avant-Garde Dadaist Hugo Ball recites his nonsense poem “Karawane” at the notorious Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1916. Avant-garde artists such as Ball consciously used their work to overturn familiar artistic conventions and challenge the assumptions of the European middle classes.

(Apic/Getty Images)

One of the earliest modernist movements was Impressionism, which blossomed in Paris in the 1870s. French artists such as Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Edgar Degas (1834–1917) and the American Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), who settled in Paris in 1875, tried to portray their sensory “impressions” in their work. Impressionists looked to the world around them for subject matter, turning their backs on traditional themes such as battles, religious scenes, and wealthy elites. Monet’s colorful and atmospheric paintings of farmland haystacks and Degas’s many pastel drawings of ballerinas exemplify the way Impressionists moved toward abstraction. Capturing a fleeting moment of color and light, in often blurry and quickly painted images, was far more important than making a heavily detailed, precise rendering of an actual object.

Page 877

In the next decades an astonishing array of new artistic movements emerged one after another. Postimpressionists and Expressionists, such as Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), built on Impressionist motifs of color and light but added a deep psychological element to their pictures, reflecting the attempt to search within the self and reveal (or “express”) deep inner feelings on the canvas.

After 1900 avant-garde artists increasingly challenged the art world status quo. In Paris in 1907 painter Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), along with other artists, established Cubism — a highly analytical approach to art concentrated on a complex geometry of zigzagging lines and sharply angled overlapping planes that exemplified the ongoing trend toward abstract, nonrepresentational art. In 1909 Italian Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876–1944) announced the founding of Futurism, a radical art and literary movement determined to transform the mentality of an anachronistic society. According to Marinetti, traditional culture could not deal with the advances of modern technology — automobiles, radios, telephones, phonographs, ocean liners, airplanes, the cinema, the newspaper — and the way these had changed human consciousness. Marinetti embraced the future and cast away the past, calling for radically new art forms that would express the modern condition. (See “Evaluating the Evidence 26.2: The Futurist Manifesto.”)

The shock of World War I encouraged further radicalization. In 1916 a group of international artists and intellectuals in exile in Zurich, Switzerland, championed a new movement they called Dadaism, which attacked all the familiar standards of art and delighted in outrageous behavior. The war had shown once and for all that life was meaningless, the Dadaists argued, so art should be meaningless as well. Dadaists tried to shock their audiences with what they called “anti-art,” works and public performances that were insulting and entirely nonsensical. A well-known example is a reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in which the masterpiece is ridiculed with the addition of a hand-drawn mustache and an obscene inscription. Like Futurists, Dadaists embraced the modern age and grappled with the horrors of modern war. “Art in its execution and direction is dependent on the time in which it lives, and artists are creatures of their epoch,” wrote Richard Huelsenbeck (1892–1974), one of the movement’s founders. “The highest art will be that which in its conscious content presents the thousand-fold problems of the day, the art which has been visibly shattered by the explosions of last week, which is forever trying to collect its limbs after yesterday’s crash.”4 After the war, Dadaism became an international movement, spreading to Paris, New York, and particularly Berlin in the early 1920s.

Page 879

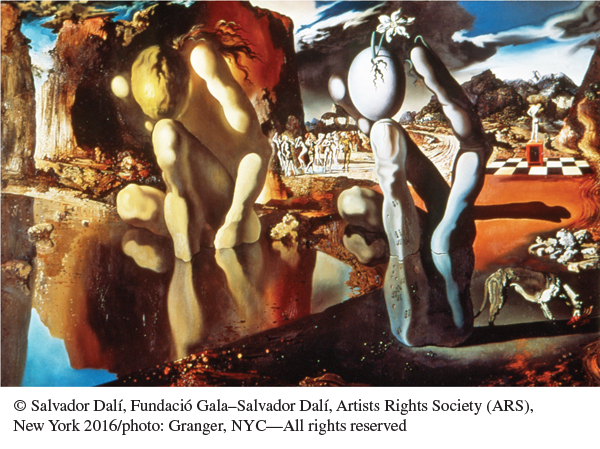

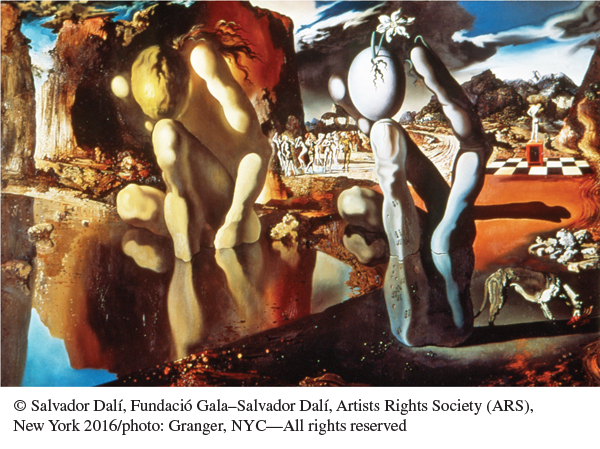

During the mid-1920s some Dadaists were attracted to Surrealism. Surrealists such as Salvador Dalí (1904–1989) were deeply influenced by Freudian psychology and portrayed images of the unconscious in their art. They painted fantastic worlds of wild dreams and uncomfortable symbols, where watches melted and giant metronomes beat time in precisely drawn but impossible alien landscapes.

Salvador Dalí, Metamorphosis of Narcissus Dalí was a leader of the Surrealist art movement, which emerged in the late 1920s. Surrealists were deeply influenced by the theories of Sigmund Freud and used strange and evocative symbols in their work to capture the inner workings of dreams and the unconscious. In this 1937 painting, Dalí plays with the Greek myth of Narcissus, who fell in love with his own reflection and drowned in a pool. What mysterious significance, if any, lies behind this surreal reordering of everyday reality?

(© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala–Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society [ARS], New York 2016/photo: Granger, NYC—All rights reserved)

Many modern artists sincerely believed that art had a radical mission. By calling attention to the bankruptcy of mainstream society, they believed, art had the power to change the world. The sometimes-nonsensical manifestos written by members of the Dadaist, Futurist, and Surrealist movements were meant to spread their ideas, challenge conventional assumptions of all kinds, and foment radical social change.

By the 1920s art and culture had become increasingly politicized. Many avant-garde artists sided with the far left; some became committed Communists. Such artists and art movements had a difficult time surviving the political crises of the 1930s. Between 1933 and 1945, when the National Socialist (Nazi) Party came to power in Germany and brought a second world war to the European continent, hundreds of artists and intellectuals — often Jews and leftists — fled to the United States to escape the war and the repressive Nazi state. After World War II, New York greatly benefited from this transfusion of talent and replaced Paris and Berlin as the world capital of modern art.