A History of Western Society: Printed Page 884

Thinking Like a Historian

The Radio Age

In the late 1920s and 1930s radio became a mass medium that reached millions of people around the world. How did the arrival of radio change the way Europeans and others experienced everyday life?

| 1 | John Reith, Broadcast over Britain, 1924. In a spirited defense of public radio, published shortly after the BBC’s first official broadcast, the corporation’s founding director championed the potential of wireless broadcasting. |

![]() Broadcasting brings relaxation and interest to many homes where such things are at a premium. It does far more; it carries direct information on a hundred subjects to innumerable men and women who will after a short time be in a position to make up their own minds on many matters of vital moment, matters which formerly they had either to receive according to the dictated and partial versions and opinions of others, or to ignore altogether. . . .

Broadcasting brings relaxation and interest to many homes where such things are at a premium. It does far more; it carries direct information on a hundred subjects to innumerable men and women who will after a short time be in a position to make up their own minds on many matters of vital moment, matters which formerly they had either to receive according to the dictated and partial versions and opinions of others, or to ignore altogether. . . .

As we conceive it, our responsibility is to carry into the greatest possible number of homes everything that is best in every department of human knowledge, endeavour and achievement, and to avoid the things which are, or may be hurtful. It is occasionally indicated to us that we are apparently setting out to give the public what we think they need — and not what they want, but few know what they want, and very few what they need. There is often no difference. . . .

I expect the day will come when, for those who wish it, in the home or office, the news of the world may be received in any quarter of the globe. . . .

Because we broadcast certain items with no permanent value, ethical or educational, it does not follow that we have failed in an ideal to transmit good things, and such as will tend to raise the general ethical or educational standard. There is no harm in trivial things; in themselves they may even be unquestionably beneficial for they may assist the more serious work by providing the measure of salt which seasons. . . .

The whole service which is conducted by wireless broadcasting may be taken as the expression of a new and better relationship between man and man. . . .

Broadcasting may help to show that mankind is a unity and that the mighty heritage, material, moral, and spiritual, if meant for the good of any, is meant for the good of all, and this is conveyed in its operations.

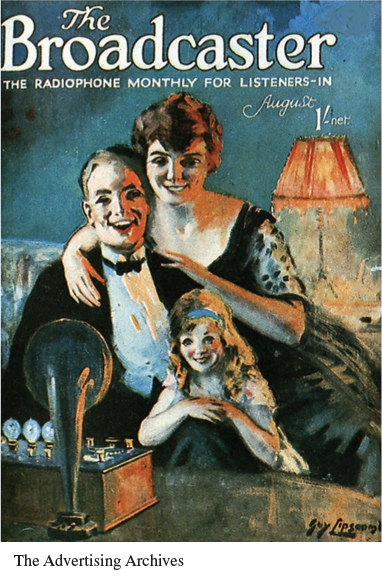

| 2 | The Broadcaster, ca. 1925. Radio transformed the way millions of listeners spent their leisure time and organized their households, and fan magazines like The Broadcaster helped broaden its appeal. As this cover illustration suggests, excited listeners would often install a radio set in a prominent location in the family living room. |

| 3 |

Christmas Day radio programming in western Germany, 1928. By the late 1920s the radio audience in the Münster- |

| Tuesday, 25 December | |

| 6:00 | Broadcast of the Christmas Mass from the [Protestant] Mother Church in Unterbarmen. [Includes community and choir singing, a Christmas sermon, and organ music by J. S. Bach.] |

| 9:00 | Ringing Church Bells from St. Gereon’s Basilica, Cologne. |

| 9:05 | Catholic Morning Service. [Includes sermon on the “Christmas Message,” solo and choir performances of Christmas music.] |

| 11:00 | University Professor Dr. J. Verweyen: On the Origins of the Christmas Holiday. . . . |

| 12:35 | Hanns Brauckmann, Christmas in the Holy Lands. . . . |

| 2:40 | Pastor Dr. Girkon Soest: Christmas in the Fine Arts. . . . |

| 3:30 | Children’s Hour. “The Christ Child’s Way Home.”. . . . |

| 4:40 | Broadcast of the Glockenspiel Concert from St. John’s Cathedral in Hertogenbosch [Holland]. [Includes performances of church and family Christmas carols.] |

| 5:40 | Christmas Songs. . . . |

| 7:00 | “Holy Night.” A Christmas legend by Ludwig Thoma recited in Upper Bavarian dialect . . . with zither. |

| 8:00 | Christmas Concert. [Includes a variety of classical Christmas music] . . . |

| Intermission: An Hour for the Betrothed. [Includes wedding music by famous composers; it was customary for Germans to get engaged on Christmas Eve and Day.] | |

| Until | |

| 1:00 A.M. | Evening Music and Dance Music. [Includes waltz, foxtrot, slowfox, tango, and one- |

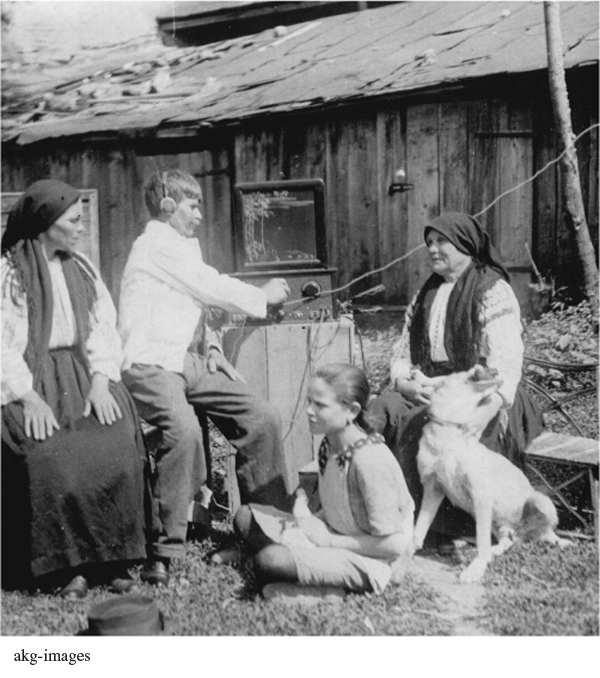

| 4 | Listening to the radio in a Romanian village, ca. 1935. Radio took some time to penetrate Europe’s less wealthy, rural areas. Eventually, however, broadcasting’s transformative effects reached the European hinterlands. |

| 5 | Official listening numbers, Germany, 1923–1938. |

| Number of Radios Registered in Germany, 1923–1938 | |||

| 1923 | 467 | 1931 | 3,509,509 |

| 1924 | 1,580 | 1932 | 3,981,000 |

| 1925 | 548,749 | 1933 | 4,307,722 |

| 1926 | 1,022,299 | 1934 | 5,052,607 |

| 1927 | 1,376,564 | 1935 | 6,142,921 |

| 1928 | 2,009,842 | 1936 | 7,192,000 |

| 1929 | 2,635,567 | 1937 | 8,167,975 |

| 1930 | 3,066,682 | 1938 | 9,0874,454 |

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

- What, according to director John Reith in Source 1, are the main goals of the BBC?

- What do Sources 2–5 reveal about radio’s impact on everyday life? Does this evidence help explain the larger impact of modern consumer culture on Western society?

- How would listening to radio change the experience of a “traditional” Christmas (see Source 3)? Who is the target audience for the holiday broadcast?

- Consider the figures in Source 5. Do these numbers accurately represent the number of listeners in the radio audience? Can historians use them to estimate the popularity of radio in the 1920s and 1930s?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

According to BBC director John Reith, radio broadcasts embodied a “new and better relationship between man and man.” Radio, for Reith, had the potential to level social differences, by bringing the “material, moral, and spiritual” heritage of Western society to broad masses of ordinary people. Using the sources above, along with what you have learned in class and in this chapter, write a short essay explaining whether or not you agree. Did radio fulfill its democratic promise?

Sources: (1) John Reith, Broadcast over Britain (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1924), pp. 19, 34, 212–213, 217–218. Copyright © John Reith. Reproduced by permission of Hodder & Stoughton Ltd; (3) “Die Ründfunkwoche,” Die Sendung, December 21, 1928, p. 12, translated by Joe Perry; (5) Kate Lacey, Feminine Frequencies: Gender, German Radio, and the Public Sphere, 1923–1945 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), pp. 32, 247.