A History of Western Society: Printed Page 904

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 866

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 905

Communism and Fascism

Communism and fascism clearly shared a desire to revolutionize state and society. Yet some scholars — arguing that the differences between the two systems are more important than the similarities — have moved beyond the totalitarian model. What were the main differences between these two systems? To answer this question, it is important to consider the way ideology, or a guiding political philosophy, was linked to the use of state-

Following Marx, Soviet Communists strove to create an international brotherhood of workers. In the Communist utopia ruled by the revolutionary working class, economic exploitation would supposedly disappear and society would be based on radical social equality (see Chapter 21). Under Stalinism — the name given to the Communist system during Stalin’s rule — the state aggressively intervened in all walks of life to pursue this social leveling. Using brute force to destroy the upper and middle classes, the Stalinist state nationalized private property, pushed rapid industrialization, and collectivized agriculture (see “The Five-Year Plans”).

The Fascist vision of a new society was quite different. Leaders who embraced fascism, such as Mussolini and Hitler, claimed that they were striving to build a new community on a national — not an international — level. Extreme nationalists, and often racists, Fascists glorified war and the military. For them, the nation was the highest embodiment of the people, and the powerful leader was the materialization of the people’s collective will.

Like Communists, Fascists promised to improve the lives of ordinary workers. Fascist governments intervened in the economy, but unlike Communist regimes they did not try to level class differences and nationalize private property. Instead, they presented a vision of a community bound together by nationalism. In the ideal Fascist state, all social strata and classes would work together to build a harmonious national community.

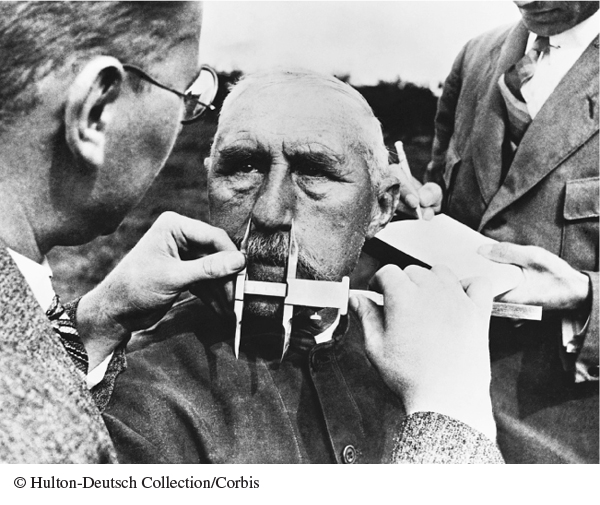

Communists and Fascists differed in another crucial respect: the question of race. Where Communists sought to build a new world around the destruction of class differences, Fascists typically sought to build a new national community grounded in racial homogeneity. Fascists embraced the doctrine of eugenics, a pseudoscience that maintained that the selective breeding of human beings could improve the general characteristics of a national population. Eugenics was popular throughout the Western world in the 1920s and 1930s and was viewed by many as a legitimate social policy. But Fascists, especially the German National Socialists, or Nazis, pushed these ideas to the extreme.

Adopting a radicalized view of eugenics, the Nazis maintained that the German nation had to be “purified” of groups of people deemed “unfit” by the regime. Following state policies intended to support what they called “racial hygiene,” Nazi authorities attempted to control, segregate, or eliminate those of “lesser value,” including Jews, Sinti and Roma (often called Gypsies, a term that can have pejorative connotations) and other ethnic minorities, homosexuals, and people suffering from chronic mental or physical disabilities. The pursuit of “racial hygiene” ultimately led to the Holocaust, the attempt to purge Germany and Europe of all Jews and other undesirable groups by mass killing during World War II (see “The Holocaust”). Though the Soviets readily persecuted specific ethnic groups they believed were disloyal to the Communist state, in general they justified these attacks using ideologies of class rather than race or biology.

Perhaps because both championed the overthrow of existing society, Communists and Fascists were sworn enemies. The result was a clash of ideologies, which was in large part responsible for the horrific destruction and loss of life in the middle of the twentieth century. Explaining the nature of totalitarian dictatorships thus remains a crucial project for historians, even as they look more closely at the ideological differences between communism and fascism.

One important set of questions explores the way dictatorial regimes generated popular consensus. Neither Hitler nor Stalin ever achieved the total control each sought. Nor did they rule alone; modern dictators need the help of large state bureaucracies and the cooperation of large numbers of ordinary people. Which was more important for generating popular support: terror and coercion or material rewards? Under what circumstances did people resist or perpetrate totalitarian tyranny? These questions lead us toward what Holocaust survivor Primo Levi called the “gray zone” of moral compromise, which defined everyday life in totalitarian societies. (See “Individuals in Society: Primo Levi.”)