A History of Western Society: Printed Page 958

Chapter Chronology

Living in the Past

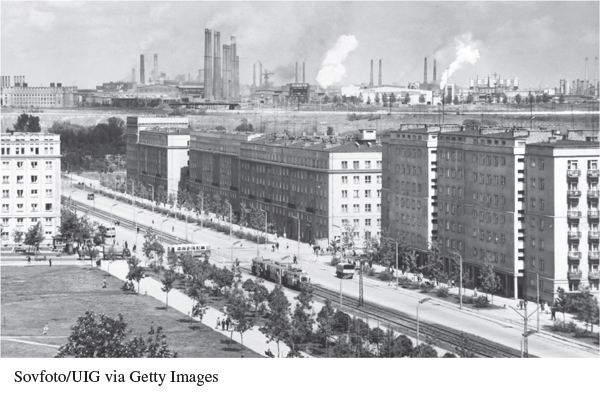

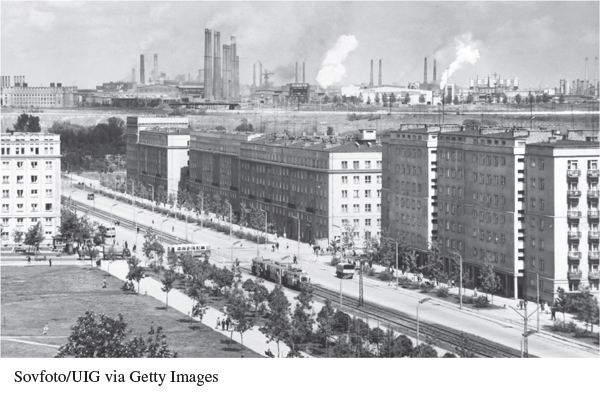

A Model Socialist Steel Town

Page 958

S teel was king in the postwar Soviet bloc. On both sides of the iron curtain, economic recovery required the development of heavy industry, but socialist planners were especially eager to promote large-scale industrial production centered on coal, iron, and steel. Following Soviet examples, East Bloc countries built massive industrial works and model socialist cities to house the workers. Among these was Nowa Huta (NOH-vuh HOO-tuh; New Foundry), a steel town erected in the early 1950s on the outskirts of Kraków, Poland.

Nowa Huta was one of the grandest construction projects of the Stalinist era. By the mid-1960s Polish leaders bragged that the massive Lenin Steelworks produced more steel per day than any foundry in Europe. They were equally proud of the city that surrounded the mills, also built with Soviet assistance. The monumental Central Square, complete with an imposing statue of Lenin, was the center of the planned city. Streets radiated out into blocks of workers’ apartment buildings designed by socialist architects. In theory, Nowa Huta brought together working and living space and included everything a working family might need: green space, department and grocery stores, recreation facilities, kindergartens and schools, cultural centers, and an extensive streetcar system. And indeed, Nowa Huta created real opportunities for Polish workers. Many moved from the farm to the city, where they enjoyed relatively good housing and good wages. By 1957 over one hundred thousand people lived in Nowa Huta, many of them employed at the steelworks.

The main square of Nowa Huta with the Lenin Steelworks foundry in the background

(Sovfoto/UIG via Getty Images)

According to propagandists, cities like Nowa Huta proved that the East could surpass the West in terms of industrial output while creating humane and equitable living spaces. At mass rallies and workplace meetings—attendance was mandatory—workers and their families listened to lengthy speeches about the honor of simple labor and the superiority of socialism. But the grand experiment revealed some of the weaknesses of the East Bloc economy. Under party oversight and strict workplace discipline, workers labored to meet demanding production quotas. Despite protests from the mostly Catholic workers, the Communist authorities sought to repress religious belief and refused to build a church until 1966. Pollution from the foundry fouled the air and damaged Kraków’s historic architecture. And by the mid-1970s the steel produced by the “tiger nations” of East Asia was better and less expensive than that made at Nowa Huta; the foundry could no longer compete in global markets. The Communist Party clung to its vision of the workers’ state, and continued government subsidies helped bankrupt the Polish state. Today, most of the steel plant is closed, but visitors can still explore an important example of socialist planning and ponder everyday life in a model industrial suburb.

At the opening of the blast furnace at the Lenin Steelworks in Nowa Huta in July 1954, the vice-chairman of the Polish Council of Ministers awards the “Standard of Labor” to a production engineer. Such official ceremonies were common practice during the Communist years.

(Sovfoto/UIG via Getty Images)

According to socialist planners, the newly built workers’ apartments at Nowa Huta had everything a growing family could want, though the pleasant scene depicted in this photo stands in contrast to the difficult working conditions and the state repression of Catholicism that led to popular unrest.

(Sovfoto/UIG via Getty Images)

- How did planned cities like Nowa Huta reflect and promote socialist values?

- Why would Polish leaders continue to support Nowa Huta when its products were no longer competitive?

- Imagine yourself a worker in Nowa Huta. What would you find appealing about the living conditions? What would you find objectionable?