A History of Western Society: Printed Page 968

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 931

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 972

Chapter Chronology

Decolonization in Africa

In less than a decade, most of Africa won independence from European imperialism, a remarkable movement of world historical importance. In much of the continent south of the Sahara, decolonization proceeded relatively smoothly. Yet the new African states were quickly caught up in the struggles between the Cold War superpowers, and decolonization all too often left a lasting legacy of violence, economic decline, and political conflict (see Map 28.3).

Starting in 1957 most of Britain’s African colonies achieved independence with little or no bloodshed and then entered a very loose association with Britain as members of the British Commonwealth. Ghana, Nigeria, Tanzania, and other countries gained independence in this way, but there were exceptions to this relatively smooth transfer of power. In Kenya, British forces brutally crushed the nationalist Mau Mau rebellion in the early 1950s, but nonetheless recognized Kenyan independence in 1963. In South Africa, the white-dominated government left the Commonwealth in 1961 and declared an independent republic in order to preserve apartheid — an exploitative system of racial segregation enforced by law.

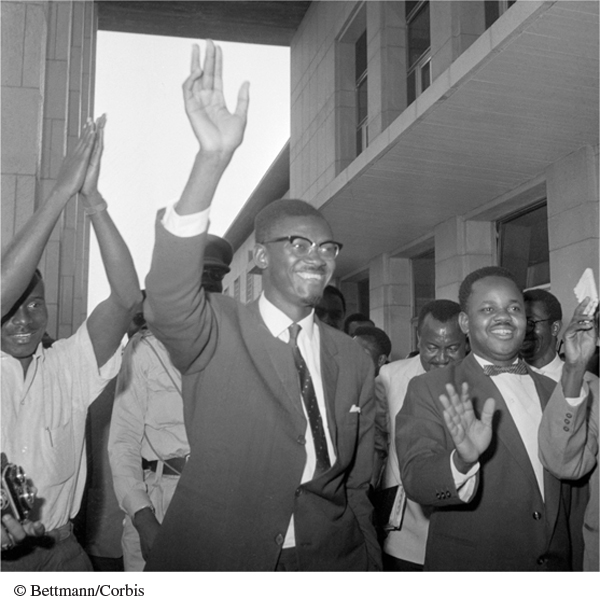

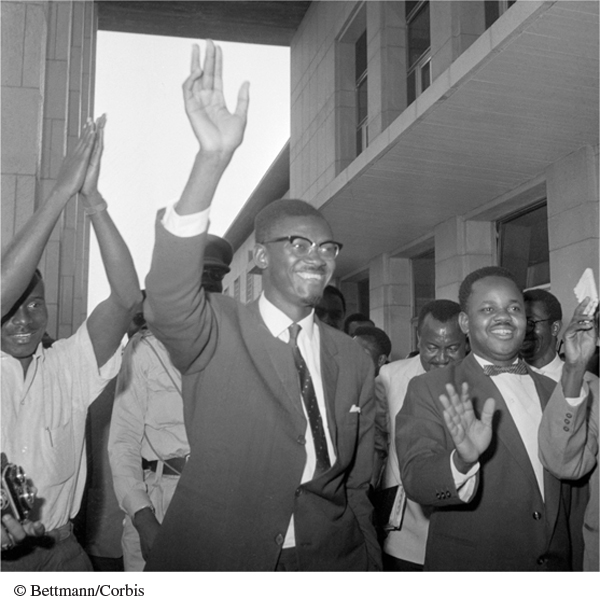

The decolonization of the Belgian Congo was one of the great tragedies of the Cold War. Belgian leaders, profiting from the colony’s wealth of natural resources and proud of their small nation’s imperial status, maintained a system of apartheid there and dragged their feet in granting independence. These conditions sparked an anticolonial movement that grew increasingly aggressive in the late 1950s under the able leadership of the charismatic Patrice Lumumba. In January 1960 the Belgians gave in and hastily announced that the Congo would be independent six months later, a schedule that was irresponsibly fast. Lumumba was chosen prime minister in democratic elections, but when the Belgians pulled out on schedule, the new government was entirely unprepared. Chaos broke out when the Congolese army attacked Belgian military officers who remained in the country.

Decolonization in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Flushed with victory, the democratically elected Congolese premier Patrice Lumumba waves as he leaves the National Senate on September 8, 1960. Lumumba had just received a 41–2 vote of confidence that confirmed his leadership position. Four months later he was assassinated in a military coup.

(© Bettmann/Corbis)

Page 969

With substantial financial investments in the Congo, the United States and western Europe worried that the new nation might fall into Soviet hands. U.S. leaders cast Lumumba as a Soviet proxy, an oversimplification of his nonalignment policies, and American anxiety increased when Lumumba asked the U.S.S.R. for aid and protection. A cable from the CIA chief in the Congo revealed the way Cold War anxieties framed the situation:

Embassy and station believe Congo experiencing classic Communist takeover government. . . . Whether or not Lumumba actually Commie or just playing Commie game to assist solidifying his power, anti-West forces rapidly increasing power [in] Congo and there may be little time left in which to take action to avoid another Cuba.6

In a troubling example of containment in action, the CIA helped implement a military coup against Lumumba, who was captured and then assassinated. The military set up a U.S.-backed dictatorship under the corrupt general Joseph Mobutu. Mobutu ruled until 1997 and became one of the world’s wealthiest men, while the Congo remained one of the poorest, most violent, and most politically torn countries in the world.

French colonies in Africa followed several roads to independence. Like the British, the French offered most of their African colonies the choice of a total break or independence within a kind of French commonwealth. All but one of the new states chose the latter option, largely because they identified with French culture and wanted aid from their former colonizer. The French were eager to help — provided the former colonies accepted close economic ties on French terms. As in the past, the French and their Common Market partners, who helped foot the bill, saw themselves as continuing their civilizing mission in sub-Saharan Africa (see Chapter 24). More important, they saw in Africa raw materials for their factories, markets for their industrial goods, outlets for profitable investment, and good temporary jobs for their engineers and teachers.

Things were far more difficult in the French colony of Algeria, a large Muslim state on the Mediterranean Sea where some 1.2 million white European settlers, including some 800,000 French, had taken up permanent residency by the 1950s. Nicknamed pieds-noirs (literally “black feet”), many of these Europeans had raised families in Algeria for three or four generations, and they enforced a two-tiered system of citizenship, dominating politics and the economy. When Algerian rebels, inspired by Islamic fundamentalism and Communist ideals, established the National Liberation Front (FLN) and revolted against French colonialism in the early 1950s, the presence of the pieds-noirs complicated matters. Worried about their position in the colony, the pieds-noirs pressured the French government to help them. In response, France sent some 400,000 troops to crush the FLN and put down the revolt. (See “Thinking Like a Historian: Violence and the Algerian War.”)

The resulting Algerian War — long, bloody, and marred by atrocities committed on both sides — lasted from 1954 to 1962. FLN radicals repeatedly attacked pied-noir civilians in savage terrorist attacks, while the French army engaged in systematic torture, mass arrests (often of innocent suspects), and the forced relocation and internment of millions of Muslim civilians suspected of supporting the insurgents. By 1958 French forces had successfully limited FLN military actions, but their disproportionate use of force effectively encouraged many Muslims to support or join the FLN. News reports about torture and abuse of civilians turned significant elements of French public opinion against the war, and international outrage further pressured French leaders to end the conflict. Efforts to open peace talks led to a revolt by the Algerian French and threats of a coup d’état by the French army. In 1958 the immensely popular General Charles de Gaulle was reinstated as French prime minister as part of the movement to keep Algeria French. His appointment at first calmed the army, the pieds-noirs, and the French public.

Page 972

Yet to the dismay of the pieds-noirs and army hardliners, de Gaulle pragmatically moved toward Algerian self-determination. In 1961 furious pieds-noirs and army leaders formed the OAS (Secret Army Organization) and opened a terrorist revolt against Muslim Algerians and the French government. In April of that year the OAS mounted an all-out but short-lived putsch, taking over Algiers and threatening the government in Paris. Loyal army units defeated the rebellion, the leading generals were purged, and negotiations between the French government and FLN leaders continued. In April 1962, after more than a century of French rule, Algeria became independent under the FLN. Then in a massive postindependence exodus, over 1 million pieds-noirs fled to France and the Americas.

By the mid-1960s most African states had won independence, some through bloody insurrections. There were exceptions: Portugal, for one, waged war against independence movements in Angola and Mozambique until the 1970s. Even in liberated countries, the colonial legacy had long-term negative effects. South African blacks still longed for liberation from apartheid, and white rulers in Rhodesia continued a bloody civil war against African insurgents until 1979. Elsewhere African leaders may have expressed support for socialist or democratic principles in order to win aid from the superpowers. In practice, however, corrupt and authoritarian African leaders like Mobutu in the Congo often established lasting authoritarian dictatorships and enriched themselves at the expense of their populations.

Even after decolonization, western European countries managed to increase their economic and cultural ties with their former African colonies in the 1960s and 1970s. Above all, they used the lure of special trading privileges and provided heavy investment in French- and English-language education to enhance a powerful Western presence in the new African states. This situation led a variety of leaders and scholars to charge that western Europe (and the United States) had imposed a system of neocolonialism on the former colonies. According to this view, neocolonialism was a system designed to perpetuate Western economic domination and undermine the promise of political independence, thereby extending to Africa (and much of Asia) the kind of economic subordination that the United States had imposed on Latin America in the nineteenth century.