A History of Western Society: Printed Page 1002

Thinking Like a Historian

The New Environmentalism

The environmentalism of the late 1960s and 1970s readily drew on earlier nineteenth-

| 1 | Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, 1962. Rachel Carson’s highly readable polemic specifically targeted the U.S. pesticide industry, though the pathbreaking marine biologist and conservationist made larger claims about the great chains of being that enmeshed humans in their natural environment. |

![]() For each of us, as for the robin in Michigan or the salmon in the Miramichi, this is a problem of ecology, of interrelationships, of interdependence. We poison the caddis flies in a stream and the salmon runs dwindle and die. We poison the gnats in a lake and the poison travels from link to link of the food chain and soon the birds of the lake margins become its victims. We spray our elms and the following springs are silent of robin song, not because we sprayed the robins directly but because the poison traveled, step by step, through the now familiar elm leaf–earthworm–robin cycle. These are matters of record, observable, part of the visible world around us. They reflect the web of life — or death — that scientists know as ecology. . . .

For each of us, as for the robin in Michigan or the salmon in the Miramichi, this is a problem of ecology, of interrelationships, of interdependence. We poison the caddis flies in a stream and the salmon runs dwindle and die. We poison the gnats in a lake and the poison travels from link to link of the food chain and soon the birds of the lake margins become its victims. We spray our elms and the following springs are silent of robin song, not because we sprayed the robins directly but because the poison traveled, step by step, through the now familiar elm leaf–earthworm–robin cycle. These are matters of record, observable, part of the visible world around us. They reflect the web of life — or death — that scientists know as ecology. . . .

We stand now where two roads diverge. But unlike the roads in Robert Frost’s familiar poem, they are not equally fair. The road we have long been traveling is deceptively easy, a smooth superhighway on which we progress with great speed, but at its end lies disaster. The other fork of the road — the one less traveled by — offers our last, our only chance to reach a destination that assures the preservation of the earth.

The choice is, after all, ours to make.

| 2 | Arne Naess, “The Deep Ecology Platform,” 1984. Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess was a founder of the Deep Ecology wilderness movement. His vision of “biospheric egalitarianism” rejected notions that humans stood above or outside of nature and called on activists to take a radical stand in defense of the natural world. |

![]()

1. The well-

2. Richness and diversity of life forms contribute to the realization of these values and are also values in themselves.

3. Humans have no right to reduce this richness and diversity except to satisfy vital needs.

4. Present human interference with the nonhuman world is excessive, and the situation is rapidly worsening.

5. The flourishing of human life and cultures is compatible with a substantial decrease of the human population. The flourishing of nonhuman life requires such a decrease.

6. Policies must therefore be changed. The changes in policies affect basic economic, technological, and ideological structures. The resulting state of affairs will be deeply different from the present.

7. The ideological change is mainly that of appreciating life quality (dwelling in situations of inherent worth) rather than adhering to an increasingly higher standard of living. There will be a profound awareness of the difference between big and great.

8. Those who subscribe to the foregoing points have an obligation directly or indirectly to participate in the attempt to implement the necessary changes.

| 3 | Rudolf Bahro, “Some Preconditions for Resolving the Ecology Crisis,” 1979. Rudolf Bahro, a founding member of the West German Green Party who compared the earth’s environment to the doomed ocean liner Titanic, called for radical intervention in the structures of corporate capitalism to prevent the looming disaster. |

![]() The ecology crisis is insoluble unless we work at the same time at overcoming the confrontation of military blocs. It is insoluble without a resolute policy of détente and disarmament, one that renounces all demands for subverting other countries. . . .

The ecology crisis is insoluble unless we work at the same time at overcoming the confrontation of military blocs. It is insoluble without a resolute policy of détente and disarmament, one that renounces all demands for subverting other countries. . . .

The ecology crisis is insoluble without a world order on the North-

The ecology crisis is insoluble without a decisive breakthrough towards social justice in our own country and without a swift equalization of social differences throughout Western Europe. . . .

If all this is brought to a common denominator, the conclusion is as follows: The ecology crisis is insoluble under capitalism. We have to get rid of the capitalist manner of regulating the economy and above all of the capitalist driving mechanism, for a start at least bringing it under control. In other words, there is no solution to the ecol-

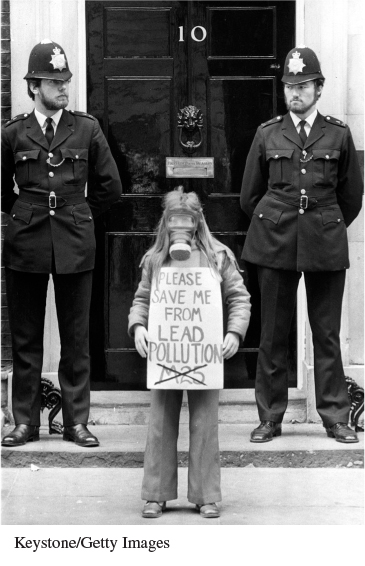

| 4 |

“Please Save Me from Lead Pollution,” 1978. A nine- |

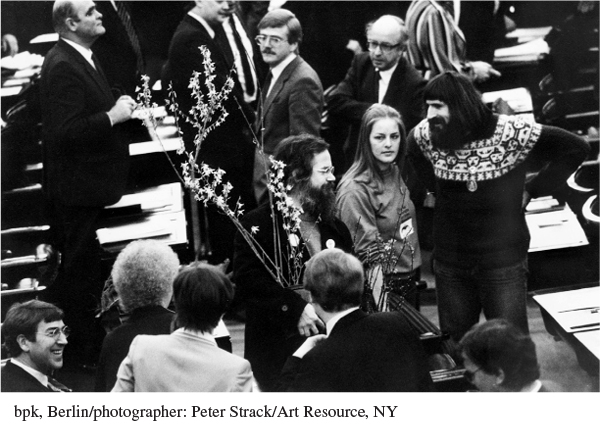

| 5 | Green Party representatives enter the West German parliament, 1983. Members of the West German “Greens” won enough votes to send several representatives to the Bundestag (parliament) for the first time in 1983, a significant victory for the environmental movements that emerged in the 1970s. |

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

- Compare and contrast the arguments made in Sources 1, 2, and 3. What do they share? What are the most significant differences?

- In Sources 4 and 5, how do environmental activists use visual presentation and symbolism to assert their political beliefs? In Source 5, how do the more traditionally dressed members of the parliament react to the Green Party members in their midst?

- Do the arguments in these sources express continuities with the ideas of the 1960s counterculture, or was the environmentalism of the 1970s and 1980s something new?

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

The environmental activists of the 1970s and 1980s were a diverse group with diverse opinions about the ways to address environmental issues. Using the sources above, along with what you have learned in class and in Chapters 28 and 29, write a short essay that explores the impact of environmentalism on political debate in the late twentieth century. How did environmental activists combine ethical, economic, and scientific critiques?

Sources: (1) Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2002), pp. 189, 277; (2) Bill Devall and George Sessions, Deep Ecology (Salt Lake City: G. M. Smith, 1985), p. 70; (4) Rudolf Bahro, Socialism and Survival (London: Merlin Books, 1982), pp. 41–43.