A History of Western Society: Printed Page 1037

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 999

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 1043

Chapter Chronology

Changing Immigration Flows

As European demographic vitality waned in the 1990s, a surge of migrants from the former Soviet Bloc, Africa, and most recently the Middle East headed for western Europe. Some migrants entered the European Union legally, with proper documentation, but increasing numbers were smuggled in past beefed-up border patrols. Large-scale immigration, both documented and undocumented, emerged as a critical and controversial issue.

Historically a source rather than a destination of immigrants, western Europe saw rising numbers of immigrants in postcolonial population movements beginning in the 1950s, augmented by the influx of manual laborers in its boom years from about 1960 until about 1973 (see Chapter 28). A new and different surge of migration into western Europe began in the 1990s. The collapse of communism in the East Bloc and savage civil wars in Yugoslavia drove hundreds of thousands of refugees westward. Equally brutal conflicts in Somalia and Rwanda, the U.S.-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and then the turmoil in North Africa and the Middle East unleashed by the “Arab Spring,” brought hundreds of thousands more. In 2013 immigration to the EU from nonmember countries topped 1.7 million people.

Undocumented or irregular immigration into the European Union also exploded. The number of irregular migrants is difficult to quantify, but in 2014 approximately 260,000 non-European nationals were turned back at Europe’s borders, while almost 550,000 irregular migrants already lived in the EU. That same year, about 275,000 migrants entered Europe irregularly, an increase of almost 140 percent from 2013.7

Why was Europe such an attractive destination for non-European migrants, regular and irregular? First, even with all the economic problems of western Europe, economic opportunity undoubtedly was a major attraction for immigrants. Germans, for example, earned on average three and a half times more than neighboring Poles, who in turn earned much more than people farther east and in North Africa. In 1998 most European Union states abolished all border controls; entrance into one country allowed for unimpeded travel almost anywhere (though Ireland and the United Kingdom opted out of this agreement). This meant that irregular migrants could enter across the relatively lax borders of Greece and south-central Europe, and then move north across the continent in search of refuge and jobs.

Second, EU immigration policy offered migrants the possibility of acquiring asylum status, if they could demonstrate that they faced severe persecution, based on race, nationality, religion, political belief, or membership in a specific social group in their home countries. Many migrants turned to Europe as they fled civil wars in Syria and Iraq, violence in Libya, and poverty and harsh social and political repression in parts of Africa. The rules for attaining asylum status varied by nation, though Germany and Sweden offered relatively liberal policies, housing for applicants, and high benefit payments (still only about $425 per month, per adult). The regulations were nonetheless restrictive: though numerous migrants applied for asylum, after an average fifteen-month wait many were rejected, classified as illegal job seekers, and expelled.

Irregular immigration was aided by powerful criminal gangs that smuggled people for profit. In the 1990s these gangs contributed to the large number of young female illegal immigrants from eastern Europe, especially Russia and Ukraine. Often lured by criminals promising jobs as maids or waitresses, these women were often trafficked into the most prosperous parts of Europe and forced into prostitution.

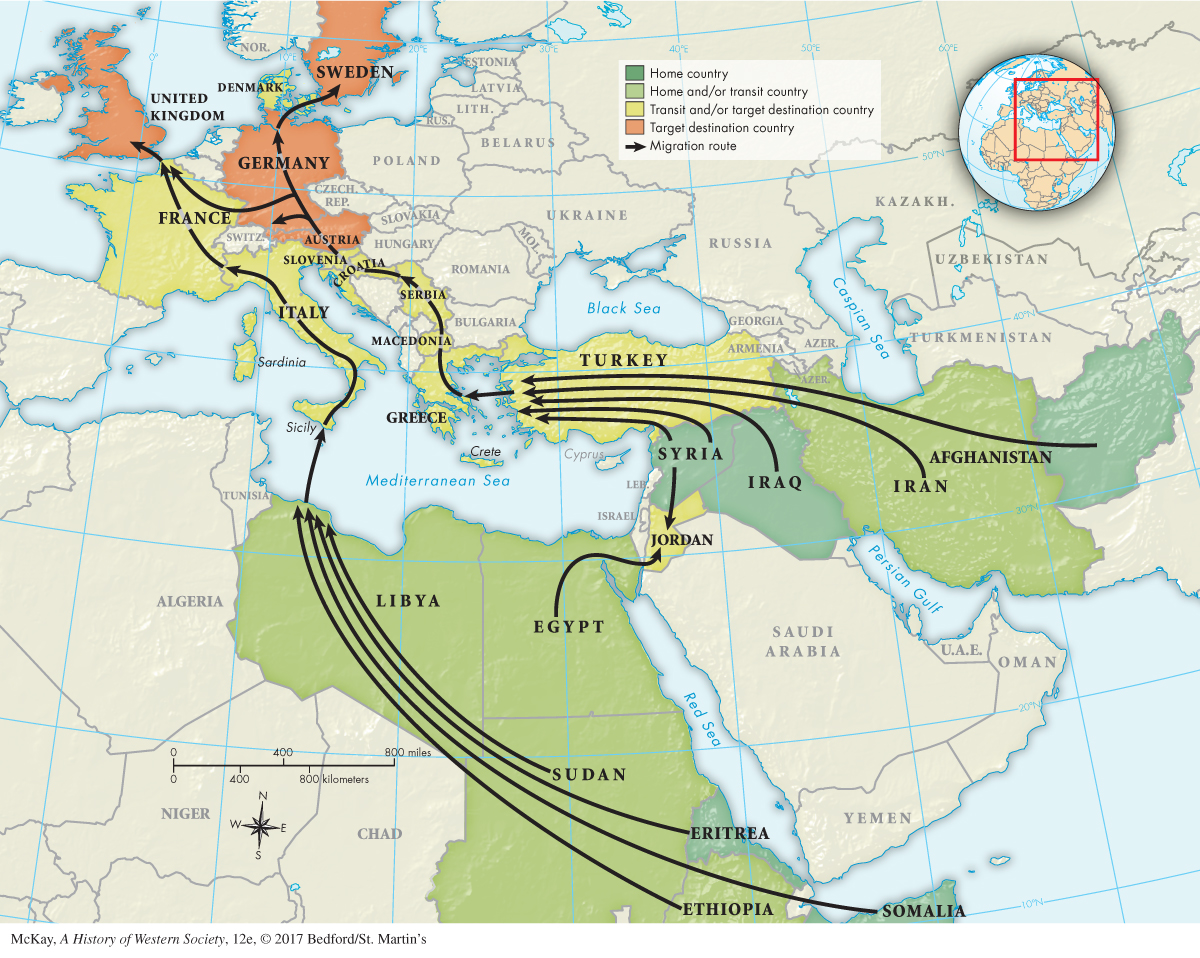

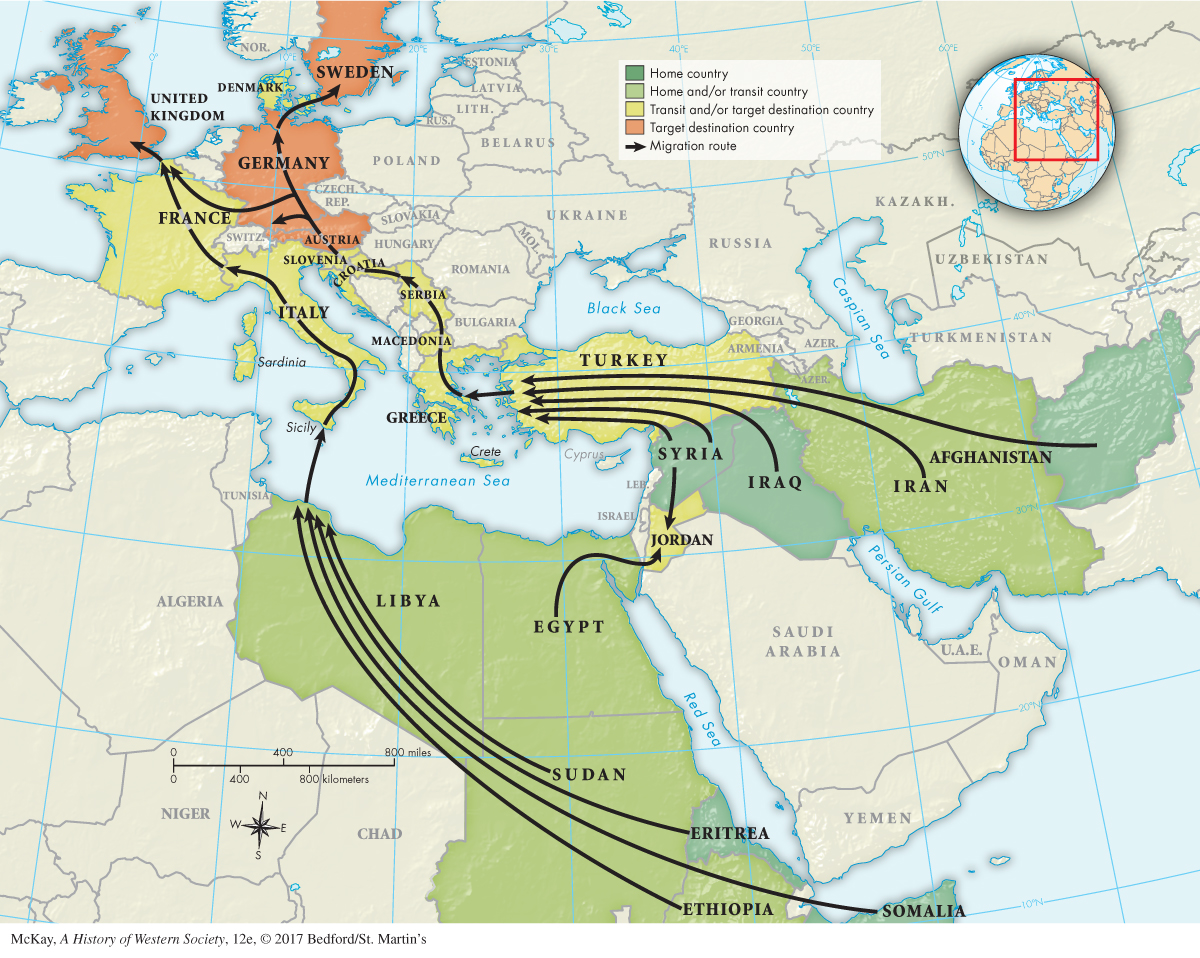

More recently, immigration flows have shifted to reflect the dislocation that emerged in North Africa and the Middle East in the wake of the failed “Arab Spring” and the war against the Islamic State (see “Turmoil in the Muslim World”). Smugglers with a callous disregard for the well-being of their charges can demand thousands of euros to bring undocumented migrants from North Africa and the Middle East across the Mediterranean into Spain and Italy; the safer and less expensive route across Turkey and Greece and the north into more prosperous European countries is particularly well traveled (Map 30.4).

Figure 30.4: MAP 30.4 Major Migration Routes into Contemporary Europe In the wake of wars and the collapse of the Arab Spring, in-migration from northern Africa and the Middle East into Europe reached crisis proportions. Aided by smugglers, thousands of migrants traveled two main routes: through Libya and across the Mediterranean Sea into southern Italy, and across Turkey to close-by Greek islands and then north through the Balkans. Countries with relatively lenient refugee regulations, such as Sweden and Germany, were favorite destinations. Under the so-called Schengen Agreement, the EU’s open-border policy made travel through Europe fairly easy. As the number of migrants increased in fall 2015 and spring 2016, however, European politicians began to close national borders, and many migrants were stranded in quickly built refugee camps.

Europe’s Refugee Crisis A volunteer helps Middle Eastern refugees ashore at the Greek island of Lesbos on November 29, 2015. Exhausted and emotional, they traveled by boat from Turkey. Under Europe’s system of open internal borders, the island’s thinly patrolled, easily accessible coastline, within sight of the Turkish coast, offered a tempting entry into the European Union for migrants ultimately seeking residence in Germany or Sweden. In fall and early winter of 2015–2016, about five thousand refugees reached Europe each day along the so-called Balkan migrant route. Their unprecedented numbers stoked anti-immigrant tensions across Europe and called into question the internal open-border system.

(Oage Elif Kizil/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Page 1038

In the summer of 2015 the migration issue reached crisis proportions. Tens of thousands of migrants, most displaced by war in Syria and Iraq, entered Hungary through Serbia and struggled to travel into more hospitable Austria, Germany, and northern Europe. Others continued to enter the EU through the relatively accessible Greek islands. As Germany promised homes for eight hundred thousand migrants and encouraged other EU nations to take their share, thousands of migrants choked train and bus stations on the Hungarian-Austrian border. Others languished in quickly established refugee camps built in northern Greece and the Hungarian countryside, and Hungary’s anti-immigrant government quickly built a 108-mile razor-wire fence along the border with Serbia to squelch further movement.

Page 1039

The discovery of seventy-one dead migrants locked in an abandoned truck on an Austrian highway — and the deaths of thousands more who in the last several years attempted to cross the Mediterranen in rudimentary rubber rafts and leaky boats — underscored the venality of the smugglers and the human costs of uncontrolled immigration. As this text was being written, European leaders were still struggling to contain the humanitarian crisis caused by the largest movement of peoples across Europe since the end of World War II, with little end in sight.