A History of Western Society: Printed Page 1054

The Past Living Now

Remembering the Holocaust

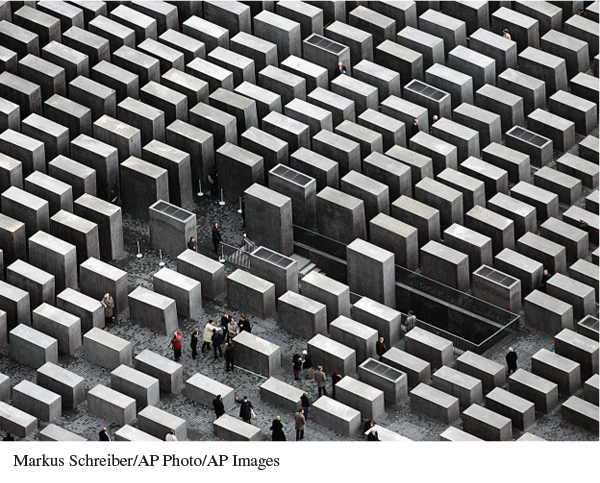

B erlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, a somber monument of 2,711 concrete slabs on a vast, uneven plain, stands just footsteps away from the Brandenburg Gate at the city’s center. Opened in 2005, the memorial commemorates the almost 6 million Jews murdered by the Nazis during World War II. Its blank walls and forbidding passageways symbolize the brutality of crimes against humanity that stretch the limits of understanding, but may also remind viewers of the difficulty of remembering those monstrous events, which played out in such vastly different ways across Europe.

In the first postwar decades, Europeans paid little attention to Nazi genocide. Though Allied leaders promised liberation from Nazi barbarism, they seldom mentioned Jews; the Allies aimed to push back the Germans, not stop genocide. After the war Europeans rebuilt cities, homes, and families and remembered their personal losses; the Jews, now gone, were too easy to forget. There was another reason: German occupiers were responsible for deporting and murdering Jews, but they were not alone. Across occupied Europe, non-

In the 1960s the silence started to crack — first in Germany, the land of the perpetrators. The 1961 trial in Jerusalem of Nazi official Adolf Eichmann for crimes against humanity raised awareness, as did trials of concentration camp guards from 1963 to 1965. The youth generation of the 1960s challenged their parents’ silence about the past, and the 1979 German broadcast of the U.S.-made television miniseries Holocaust, watched by some 20 million viewers, put Nazi crimes at the center of German public consciousness.

In countries occupied by the Germans during World War II, remembering the Holocaust posed troublesome questions about complicity and collaboration. France was a key example. During the war, French officials of the Nazi-

In the East Bloc, Communist leaders readily publicized Nazi crimes, but failed to explain that Jews were the primary target of Nazi genocide. Because Marxist ideology championed the working classes, Communist interpretations of Nazi barbarism focused on workers, not Jews. At the Auschwitz Museum in Communist Poland, for example, those murdered in the camp were labeled “workers” and listed by nationality, not ethnicity or religion, thus masking the fact that over 90 percent of the camp’s 1.5 million victims were Jewish.* After communism collapsed, Poles dealt more openly with the facts; the museum at Auschwitz now clearly recognizes Jewish victims. But this new openness raised tough questions — historians have recently called attention to Polish anti-

Over the past twenty-

QUESTIONS FOR ANALYSIS

- Why would memories of the Holocaust vary from country to country and change over time? What accounts for the growing commemoration of the Holocaust?

- Find the Web sites for the museums and monuments discussed above, and compare and contrast the ways they present the Holocaust. What are the stated goals of these institutions? Can you see national differences in the ways they depict the past?