A History of Western Society: Printed Page 1021

A History of Western Society, Value Edition: Printed Page 981

A History of Western Society, Concise Edition: Printed Page 1024

Chapter Chronology

Russian Revival Under Vladimir Putin

This widespread disillusionment set the stage for the rise of Vladimir Putin (POO-tihn) (b. 1952), who was elected president as Yeltsin’s chosen successor in 2000 and re-elected in a landslide in March 2004. A colonel in the secret police during the Communist era, Putin maintained relatively liberal economic policies but re-established semi-authoritarian political rule. Critics labeled Putin’s system an “imitation democracy,” and indeed a façade of democratic institutions masked authoritarian rule from above in postcommunist Russia.1 Putin’s government maintained control with rigged elections, weak parliamentary rule, the intimidation of political opponents, and the distribution of state-owned public assets to win support of the new elite. Yet Putin’s argument that the transition to free markets required strong political rule to control corruption and prevent a collapse into complete chaos resonated with ordinary Russians worried about the disintegration of the Communist state. The president enjoyed strong popular support, at least in the first years of his rule.

Putin’s government combined authoritarian politics with economic reform. The regime clamped down on the excesses of the Oligarchs, lowered corporate and business taxes, and re-established some government control over key industries. Such reforms — aided greatly by high world prices for oil and natural gas, Russia’s most important exports — led to a decade of economic expansion, encouraging the growth of a new middle class. In 2008, however, the global financial crisis and a rapid drop in the price of oil caused a downturn, and the Russian stock market collapsed. The government initiated a $200 billion rescue plan, and the economy stabilized and returned to modest growth in 2010.

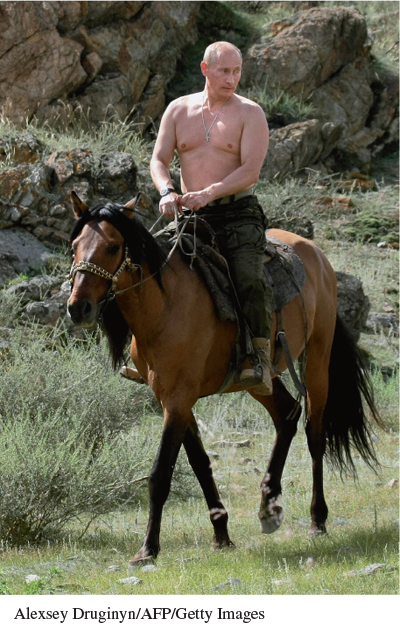

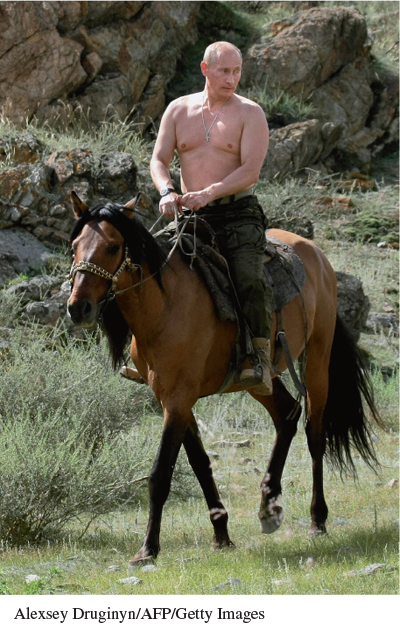

During his first two terms as president, Putin’s domestic and foreign policies proved immensely popular with a majority of Russians. His housing, education, and health-care reforms significantly improved living standards. Putin repeatedly evoked the glories of Russian history, expressed pride in the accomplishments of the Soviet Union, and downplayed the abuses of the Stalinist system; he thus capitalized on popular feelings of Russian patriotism. In addition, the Russian president centralized power in the Kremlin, increased military spending, and expanded the secret police. Putin’s carefully crafted manly image and his forceful international diplomacy soothed the country’s injured pride and symbolized its national revival.

Page 1022

In foreign relations, the president generally championed assertive anti-Western policies in an attempt to bolster Russia’s status as a great Eurasian power and world player. (See “Evaluating the Evidence 30.1: President Putin on Global Security.”) Putin forcefully opposed the expansion of NATO into the former East Bloc and regularly challenged U.S. and NATO foreign policy goals. In the Syrian civil war that broke out in 2011, for example, Russian backing of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad flew in the face of U.S. attempts to depose him. Putin’s support in summer 2015 for a deal to limit Iran’s nuclear capabilities marked a rare moment of Russian cooperation with the United States, the EU, and the United Nations.

Vladimir Putin on Vacation in 2009 After two terms as Russian president (2000–2008), Putin served as prime minister for four years before returning to the presidency in 2012. Putin’s high approval ratings were due in part to his carefully crafted image of strength and manliness.

(Alexsey Druginyn/AFP/Getty Images)

Putin’s Russia has taken an aggressive and at times interventionist stance toward the Commonwealth of Independent States, a loose confederation of most of the former Soviet republics (Map 30.1). The annexation of the Crimea in 2014 and support for insurrectionist pro-Russian rebels in eastern Ukraine are only the latest examples.

Putin’s government moved decisively to limit political opposition at home. The 2003 arrest and imprisonment for tax evasion and fraud of the corrupt oil billionaire Mikhail Khodorkovsky, an Oligarch who had openly supported opposition parties, showed early on that Putin and his United Russia Party would use state powers to stifle dissent. Though the Russian constitution guarantees freedom of the press, the government cracked down on the independent media. Using a variety of tactics, officials and pro-government businessmen influenced news reports and intimidated critical journalists. The suspicious murder in 2006 of journalist Anna Politkovskaya, a prominent critic of the government’s human rights abuses and its war in Chechnya, reinforced Western worries that the country was returning to Soviet-style press censorship.

Putin stepped down when his term limits expired in 2008. His handpicked successor, Dmitry Medvedev (mehd-VEHD-yehf ) (b. 1965), easily won election that year and then appointed Putin prime minister, leading observers to believe that the former president was still the dominant figure. This suspicion was confirmed when Putin won the presidential election of March 2012 with over 60 percent of the vote. International observers agreed that the election itself was democratic, but reported irregularities during the vote-counting process. Some fifteen thousand protesters marched through downtown Moscow to protest election fraud and the authoritarian aspects of Putin’s rule, and demonstrations accompanied the president’s inauguration that May.

Tensions between political centralization and openness continue to define Russia’s difficult road away from communism. On one hand, Putin’s return to the presidency seemed to reinforce Russia’s system of authoritarian central control. On the other, the fact that mass assemblies and marches against the president took place with relatively little repression attests to some degree of political openness and new limits on Russian state power in the twenty-first century.